In the United States, antitrust law is a collection of mostly federal laws that regulate the conduct and organization of businesses in order to promote competition and prevent unjustified monopolies. The three main U.S. antitrust statutes are the Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914, and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. These acts serve three major functions. First, Section 1 of the Sherman Act prohibits price fixing and the operation of cartels, and prohibits other collusive practices that unreasonably restrain trade. Second, Section 7 of the Clayton Act restricts the mergers and acquisitions of organizations that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. Third, Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolization.

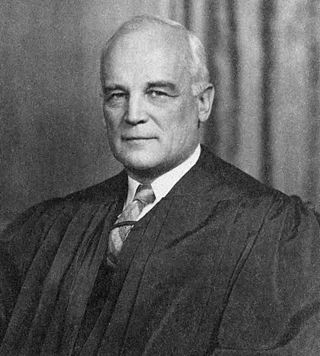

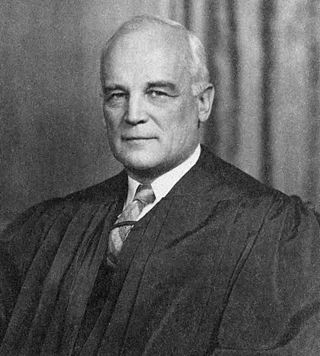

Harold Hitz Burton was an American politician and lawyer. He served as the 45th mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, as a U.S. Senator from Ohio, and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

A consent decree is an agreement or settlement that resolves a dispute between two parties without admission of guilt or liability. Most often it is such a type of settlement in the United States. The plaintiff and the defendant ask the court to enter into their agreement, and the court maintains supervision over the implementation of the decree in monetary exchanges or restructured interactions between parties. It is similar to and sometimes referred to as an antitrust decree, stipulated judgment, or consent judgment. Consent decrees are frequently used by federal courts to ensure that businesses and industries adhere to regulatory laws in areas such as antitrust law, employment discrimination, and environmental regulation.

In United States patent law, patent misuse is a patent holder's use of a patent to restrain trade beyond enforcing the exclusive rights that a lawfully obtained patent provides. If a court finds that a patent holder committed patent misuse, the court may rule that the patent holder has lost the right to enforce the patent. Patent misuse that restrains economic competition substantially can also violate United States antitrust law.

The McCarran–Ferguson Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1011-1015, is a United States federal law that exempts the business of insurance from most federal regulation, including federal antitrust laws to a limited extent. The 79th Congress passed the McCarran–Ferguson Act in 1945 after the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters Association that the federal government could regulate insurance companies under the authority of the Commerce Clause in the U.S. Constitution and that the federal antitrust laws applied to the insurance industry.

Loewe v. Lawlor, 208 U.S. 274 (1908), also referred to as the Danbury Hatters' Case, is a United States Supreme Court case in United States labor law concerning the application of antitrust laws to labor unions. The Court's decision effectively outlawed the secondary boycott as a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act, despite union arguments that their actions affected only intrastate commerce. It was also decided that individual unionists could be held personally liable for damages incurred by the activities of their union.

Silver v. New York Stock Exchange, 373 U.S. 341 (1963), was a case of the United States Supreme Court which was decided May 20, 1963. It held that the duty of self-regulation imposed upon the New York Stock Exchange by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 did not exempt it from the antitrust laws nor justify it in denying petitioners the direct-wire connections without the notice and hearing which they requested. Therefore, the Exchange's action in this case violated 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, and the NYSE is liable to petitioners under 4 and 16 of the Clayton Act.

Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar, 421 U.S. 773 (1975), was a U.S. Supreme Court decision. It stated that lawyers engage in "trade or commerce" and hence ended the legal profession's exemption from antitrust laws.

California Retail Liquor Dealers Assn. v. Midcal Aluminum, Inc., 445 U.S. 97 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court created a two-part test for the application of the state action immunity doctrine that it had previously developed in Parker v. Brown.

The Parker immunity doctrine is an exemption from liability for engaging in antitrust violations. It applies to the state when it exercises legislative authority in creating a regulation with anticompetitive effects, and to private actors when they act at the direction of the state after it has done so. The doctrine is named for the Supreme Court of the United States case in which it was initially developed, Parker v. Brown.

Rice v. Norman Williams Co., 458 U.S. 654 (1982), was a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court involving the preemption of state law by the Sherman Act. The Supreme Court held, in a 9–0 decision, that the Sherman Act did not invalidate a California law prohibiting the importing of spirits not authorized by the brand owner.

Continental Television v. GTE Sylvania, 433 U.S. 36 (1977), was an antitrust decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. It widened the scope of the "rule of reason" to exclude the jurisdiction of antitrust laws.

Pfizer Inc. v. Government of India, 434 U.S. 308 (1978), decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held that foreign states are entitled to sue for treble damages in U.S. courts, and should be recognized as "persons" under the Clayton Act.

FTC v. Actavis, Inc., 570 U.S. 136 (2013), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which the Court held that the FTC could make an antitrust challenge under the rule of reason against a so-called pay-for-delay agreement, also referred to as a reverse payment patent settlement. Such an agreement is one in which a drug patentee pays another company, ordinarily a generic drug manufacturer, to stay out of the market, thus avoiding generic competition and a challenge to patent validity. The FTC sought to establish a rule that such agreements were presumptively illegal, but the Court ruled only that the FTC could bring a case under more general antitrust principles permitting a defendant to assert justifications for its actions under the rule of reason.

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc. is the caption of several United States Supreme Court patent–related decisions, the most significant of which is a 1969 patent–antitrust and patent–misuse decision concerning the levying of patent royalties on unpatented products.

North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission, 574 U.S. 494 (2015), was a United States Supreme Court case on the scope of immunity from US antitrust law. The Supreme Court held that a state occupational licensing board that was primarily composed of persons active in the market it regulates has immunity from antitrust law only when it is actively supervised by the state. The North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners had relied on the Parker immunity doctrine, established by the Supreme Court case Parker v. Brown, which held that actions by state governments acting in their sovereignty did not violate antitrust law.

United States v. United States Gypsum Co. was a patent–antitrust case in which the United States Supreme Court decided, first, in 1948, that a patent licensing program that fixed prices of many licensees and regimented an entire industry violated the antitrust laws, and then, decided in 1950, after a remand, that appropriate relief in such cases did not extend so far as to permit licensees enjoying a compulsory, reasonable–royalty license to challenge the validity of the licensed patents. The Court also ruled, in obiter dicta, that the United States had standing to challenge the validity of patents when a patentee relied on the patents to justify its fixing prices. It held in this case, however, that the defendants violated the antitrust laws irrespective of whether the patents were valid, which made the validity issue irrelevant.