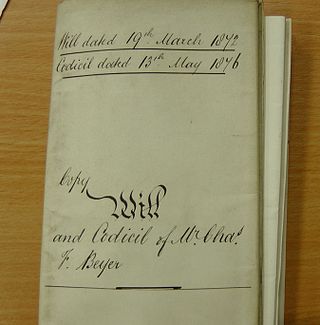

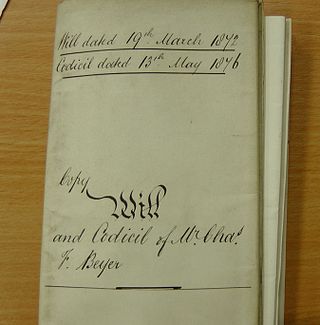

A will or testament is a legal document that expresses a person's (testator) wishes as to how their property (estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person (executor) is to manage the property until its final distribution. For the distribution (devolution) of property not determined by a will, see inheritance and intestacy.

Wills have a lengthy history.

Joint wills and mutual wills are closely related terms used in the law of wills to describe two types of testamentary writing that may be executed by a married couple to ensure that their property is disposed of identically. Neither should be confused with mirror wills which means two separate, identical wills, which may or may not also be mutual wills.

A purpose trust is a type of trust which has no beneficiaries, but instead exists for advancing some non-charitable purpose of some kind. In most jurisdictions, such trusts are not enforceable outside of certain limited and anomalous exceptions, but some countries have enacted legislation specifically to promote the use of non-charitable purpose trusts. Trusts for charitable purposes are also technically purpose trusts, but they are usually referred to simply as charitable trusts. People referring to purpose trusts are usually taken to be referring to non-charitable purpose trusts.

In law a settlor is a person who settles property on trust law for the benefit of beneficiaries. In some legal systems, a settlor is also referred to as a trustor, or occasionally, a grantor or donor. Where the trust is a testamentary trust, the settlor is usually referred to as the testator. The settlor may also be the trustee of the trust or a third party may be the trustee. In the common law of England and Wales, it has been held, controversially, that where a trustee declares an intention to transfer trust property to a trust of which he is one of several trustees, that is a valid settlement notwithstanding the property is not vested in the other trustees.

Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd[1968] UKHL 4 is a leading property, unjust enrichment and trusts case, which invented a new species of proprietary interest in English law. A "Quistclose trust" arises when an asset is given to somebody for a specific purpose and if, for whatever reason, the purpose for the transfer fails, the transferor may take back the asset.

Saunders v Vautier[1841] EWHC J82, (1841) 4 Beav 115 is a leading English trusts law case. It laid down the rule of equity which provides that, if all of the beneficiaries in the trust are of adult age and under no disability, the beneficiaries may require the trustee to transfer the legal estate to them and thereby terminate the trust. The rule has been repeatedly affirmed in common law jurisdictions, and is commonly referred to as "the rule in Saunders v Vautier" for shorthand.

A discretionary trust, in the trust law of England, Australia, Canada and other common law jurisdictions, is a trust where the beneficiaries and/or their entitlements to the trust fund are not fixed, but are determined by the criteria set out in the trust instrument by the settlor. It is sometimes referred to as a family trust in Australia or New Zealand. Where the discretionary trust is a testamentary trust, it is common for the settlor to leave a letter of wishes for the trustees to guide them as to the settlor's wishes in the exercise of their discretion. Letters of wishes are not legally binding documents.

English trust law concerns the protection of assets, usually when they are held by one party for another's benefit. Trusts were a creation of the English law of property and obligations, and share a subsequent history with countries across the Commonwealth and the United States. Trusts developed when claimants in property disputes were dissatisfied with the common law courts and petitioned the King for a just and equitable result. On the King's behalf, the Lord Chancellor developed a parallel justice system in the Court of Chancery, commonly referred as equity. Historically, trusts have mostly been used where people have left money in a will, or created family settlements, charities, or some types of business venture. After the Judicature Act 1873, England's courts of equity and common law were merged, and equitable principles took precedence. Today, trusts play an important role in financial investment, especially in unit trusts and in pension trusts. Although people are generally free to set the terms of trusts in any way they like, there is a growing body of legislation to protect beneficiaries or regulate the trust relationship, including the Trustee Act 1925, Trustee Investments Act 1961, Recognition of Trusts Act 1987, Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, Trustee Act 2000, Pensions Act 1995, Pensions Act 2004 and Charities Act 2011.

Knight v Knight (1840) 49 ER 58 is an English trusts law case, embodying a simple statement of the "three certainties" principle. This has the effect of determining whether assets can be disposed of in wills, or whether the wording of the will is too vague to allow beneficiaries to collect what appears on the face of the will to be theirs. The case has been followed in most common law jurisdictions.

The three certainties refer to a rule within English trusts law on the creation of express trusts that, to be valid, the trust instrument must show certainty of intention, subject matter and object. "Certainty of intention" means that it must be clear that the donor or testator wishes to create a trust; this is not dependent on any particular language used, and a trust can be created without the word "trust" being used, or even the donor knowing he is creating a trust. Since the 1950s, the courts have been more willing to conclude that there was intention to create a trust, rather than hold that the trust is void. "Certainty of subject matter" means that it must be clear what property is part of the trust. Historically the property must have been segregated from non-trust property; more recently, the courts have drawn a line between tangible and intangible assets, holding that with intangible assets there is not always a need for segregation. "Certainty of objects" means that it must be clear who the beneficiaries, or objects, are. The test for determining this differs depending on the type of trust; it can be that all beneficiaries must be individually identified, or that the trustees must be able to say with certainty, if a claimant comes before them, whether he is or is not a beneficiary.

The creation of express trusts in English law must involve four elements for the trust to be valid: capacity, certainty, constitution and formality. Capacity refers to the settlor's ability to create a trust in the first place; generally speaking, anyone capable of holding property can create a trust. There are exceptions for statutory bodies and corporations, and minors who usually cannot hold property can, in some circumstances, create trusts. Certainty refers to the three certainties required for a trust to be valid. The trust instrument must show certainty of intention to create a trust, certainty of what the subject matter of the trust is, and certainty of who the beneficiaries are. Where there is uncertainty for whatever reason, the trust will fail, although the courts have developed ways around this. Constitution means that for the trust to be valid, the property must have been transferred from the settlor to the trustees.

In English law, secret trusts are a class of trust defined as an arrangement between a testator and a trustee, made to come into force after death, that aims to benefit a person without having been written in a formal will. The property is given to the trustee in the will, and he would then be expected to pass it on to the real beneficiary. For these to be valid, the person seeking to enforce the trust must prove that the testator intended to form a trust, that this intention was communicated to the trustee, and that the trustee accepted his office. There are two types of secret trust — fully secret and half-secret. A fully secret trust is one with no mention in the will whatsoever. In the case of a half-secret trust, the face of the will names the trustee as trustee, but does not give the trust's terms, including the beneficiary. The most important difference lies in communication of the trust: the terms of a half-secret trust must be communicated to the trustee before the execution of the will, whereas in the case of a fully secret trust the terms may be communicated after the execution of the will, as long as this is before the testator's death.

Dillwyn v Llewelyn [1862] is an 'English' land, probate and contract law case which established an example of proprietary estoppel at the testator's wish overturning his last Will and Testament; the case concerned land in Wales demonstrating the united jurisdiction of England and Wales.

Re Baden’s Deed Trusts [1972] EWCA Civ 10 is an English trusts law case, concerning the circumstances under which a trust will be held to be uncertain. It followed on from McPhail v Doulton, where the House of Lords affirmed that upholding the settlor's intentions was of paramount importance. It dealt with the same facts as McPhail v Doulton, since the Lords had remanded the case to the Court of Appeal to be decided using the legal principles set out in McPhail.

Re Barlow's Will Trusts [1979] 1 WLR 278 is an English trusts law case, concerning certainty of the words "family" and "friends" in a will.

Re Gulbenkian’s Settlements Trusts [1968] is an English trusts law case, concerning the certainty of trusts. It held that while the 'is or is not' test was suitable for mere powers, the complete list test remained the appropriate test for discretionary trusts. It was only a year later in McPhail v Doulton that the 'is or is not' test was considered appropriate for discretionary trusts by a different panel of their lordships.

Morice v Bishop of Durham [1805] EWHC Ch J80 is an English trusts law case, concerning the policy of the beneficiary principle.

Testate succession exists under the law of succession in South Africa.

Minshull v Minshull (1737) 26 ER 260 is an English trusts law case, concerning the principle of certainty for a will, known then as a "devise".