Related Research Articles

A gladiator was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalized, and segregated even in death.

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Such oaths are often required by the laws of the state, religious body, or other organization before the person may actually exercise the powers of the office or organization. It may be administered at an inauguration, coronation, enthronement, or other ceremony connected with the taking up of office itself, or it may be administered privately. In some cases it may be administered privately and then repeated during a public ceremony.

Tertullian was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of Latin Christian literature and was an early Christian apologist and a polemicist against heresy, including contemporary Christian Gnosticism. Tertullian has been called "the father of Latin Christianity", as well as "the founder of Western theology".

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

Traditionally an oath is either a statement of fact or a promise taken by a sacrality as a sign of verity. A common legal substitute for those who conscientiously object to making sacred oaths is to give an affirmation instead. Nowadays, even when there is no notion of sanctity involved, certain promises said out loud in ceremonial or juridical purpose are referred to as oaths. "To swear" is a verb used to describe the taking of an oath, to making a solemn vow.

The Edict of Milan was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and Emperor Licinius, who controlled the Balkans, met in Mediolanum and, among other things, agreed to change policies towards Christians following the edict of toleration issued by Emperor Galerius two years earlier in Serdica. The Edict of Milan gave Christianity legal status and a reprieve from persecution but did not make it the state church of the Roman Empire, which occurred in AD 380 with the Edict of Thessalonica.

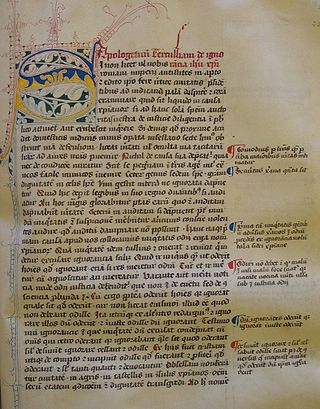

Apologeticus is a text attributed to Tertullian according to Christian tradition, consisting of apologetic and polemic. In this work Tertullian defends Christianity, demanding legal toleration and that Christians be treated as all other sects of the Roman Empire. It is in this treatise that one finds the sentence "Plures efficimur, quotiens metimur a vobis: semen est sanguis Christianorum." which has been liberally and apocryphally translated as "the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church". Alexander Souter translated this phrase as "We spring up in greater numbers the more we are mown down by you: the blood of the Christians is the seed of a new life," but even this takes liberties with the original text. "We multiply when you reap us. The blood of Christians is seed," is perhaps a more faithful, if less poetic, rendering.

Homo sacer is a figure of Roman law: a person who is banned and might be killed by anybody, but must not be sacrificed in a religious ritual. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben takes the concept as the starting point of his main work Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1998).

The right to freedom of religion in the United Kingdom is provided for in all three constituent legal systems, by devolved, national, European, and international law and treaty. Four constituent nations compose the United Kingdom, resulting in an inconsistent religious character, and there is no state church for the whole kingdom.

As the Roman Republic, and later the Roman Empire, expanded, it came to include people from a variety of cultures, and religions. The worship of an ever increasing number of deities was tolerated and accepted. The government, and the Romans in general, tended to be tolerant towards most religions and religious practices. Some religions were banned for political reasons rather than dogmatic zeal, and other rites which involved human sacrifice were banned.

A religious test is a legal requirement to swear faith to a specific religion or sect, or to renounce the same.

As with most other military forces the Roman military adopted an extensive list of decorations for military gallantry and likewise a range of punishments for military transgressions.

Christians were persecuted, sporadically and usually locally, throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the 1st century AD and ending in the 4th century. Originally a polytheistic empire in the traditions of Roman paganism and the Hellenistic religion, as Christianity spread through the empire, it came into ideological conflict with the imperial cult of ancient Rome. Pagan practices such as making sacrifices to the deified emperors or other gods were abhorrent to Christians as their beliefs prohibited idolatry. The state and other members of civic society punished Christians for treason, various rumored crimes, illegal assembly, and for introducing an alien cult that led to Roman apostasy. The first, localized Neronian persecution occurred under Emperor Nero in Rome. A more general persecution occurred during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. After a lull, persecution resumed under Emperors Decius and Trebonianus Gallus. The Decian persecution was particularly extensive. The persecution of Emperor Valerian ceased with his notable capture by the Sasanian Empire's Shapur I at the Battle of Edessa during the Roman–Persian Wars. His successor, Gallienus, halted the persecutions.

Religio licita is a phrase used in the Apologeticum of Tertullian to describe the special status of the Jews in the Roman Empire. It was not an official term in Roman law.

Roman Tunisia initially included the early ancient Roman province of Africa, later renamed Africa Vetus. As the Roman empire expanded, the present Tunisia also included part of the province of Africa Nova.

Damnatio ad bestias was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Roman Republic around the 2nd century BC, had been part of a wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

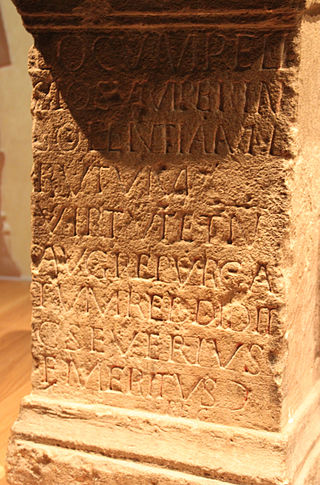

The vocabulary of ancient Roman religion was highly specialized. Its study affords important information about the religion, traditions and beliefs of the ancient Romans. This legacy is conspicuous in European cultural history in its influence on later juridical and religious vocabulary in Europe, particularly of the Christian Church. This glossary provides explanations of concepts as they were expressed in Latin pertaining to religious practices and beliefs, with links to articles on major topics such as priesthoods, forms of divination, and rituals.

Pliny the Younger, the Roman governor of Bithynia and Pontus, wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan around AD 110 and asked for counsel on dealing with the early Christian community. The letter details an account of how Pliny conducted trials of suspected Christians who appeared before him as a result of anonymous accusations and asks for the Emperor's guidance on how they should be treated.

In the Roman Empire, the Lychnapsia was a festival of lamps on August 12, widely regarded by scholars as having been held in honor of Isis. It was thus one of several official Roman holidays and observances that publicly linked the cult of Isis with Imperial cult. It is thought to be a Roman adaptation of Egyptian religious ceremonies celebrating the birthday of Isis. By the 4th century, Isiac cult was thoroughly integrated into traditional Roman religious practice, but evidence that Isis was honored by the Lychnapsia is indirect, and lychnapsia is a general word in Greek for festive lamp-lighting. In the 5th century, lychnapsia could be synonymous with lychnikon as a Christian liturgical office.

The Latin term religiō, the origin of the modern lexeme religion, is of ultimately obscure etymology. It is recorded beginning in the 1st century BC, i.e. in Classical Latin at the end of the Roman Republic, notably by Cicero, in the sense of "scrupulous or strict observance of the traditional cultus". In classic antiquity, it meant conscientiousness, sense of right, moral obligation, or duty towards anything and was used mostly in secular or mundane contexts. In religious contexts, it also meant the feelings of "awe and anxiety" caused by gods and spirits that would help Romans "live successfully".

References

- ↑ Jörg Rüpke, Domi Militiae: Die religiöse Konstruktion des Krieges in Rom (Franz Steiner, 1990), pp. 76–80.

- ↑ D. Briquel "Sur les aspects militaires du dieu ombrien Fisus Sancius" in Revue de l' histoire des religions[ full citation needed ] i p. 150-151; J. A. C. Thomas A Textbook of Roman law Amsterdam 1976 p. 74 and 105.

- ↑ Arnaldo Momigliano, Quinto contributo alla storia degli studi classici e del mondo antico (Storia e letteratura, 1975), vol. 2, pp. 975–977; Luca Grillo, The Art of Caesar's Bellum Civile: Literature, Ideology, and Community (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 60.

- ↑ Apuleius, Metamorphoses 11.15.5; Robert Schilling, "The Decline and Survival of Roman Religion," in Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992, from the French edition of 1981)

- ↑ Varro De Lingua latina V 180; Festus s.v. sacramentum p. 466 L; 511 L; Paulus Festi Epitome p.467 L.

- ↑ George Mousourakis, A Legal History of Rome (Routledge, 2007), p. 33.

- ↑ Mousourakis, A Legal History of Rome, pp. 33, 206.

- ↑ Vegetius 2.5.

- ↑ See further discussion at fustuarium

- ↑ Gladiators swore to commit their bodies to the possibility of being "burned, bound, beaten, and slain by the sword"; Petronius, Satyricon 117; Seneca, Epistulae 37.1-2.

- ↑ A.D. Nock, "The roman army and the Roman religious year", Harvard Theological Review45 (1952:187-252).

- ↑ Carlin A. Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster (Princeton University Press, 1993), pp. 14–16, 35 (note 88), 42, 45–47.

- ↑ Tertullian, De corona[ full citation needed ], as noted by Paul Stephenson, Constantine, Roman Emperor, Christian Victor, 2010:58.