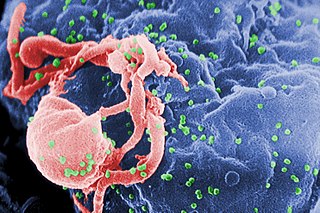

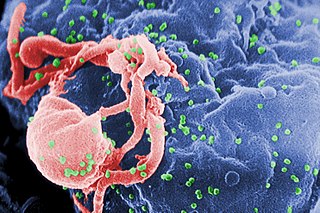

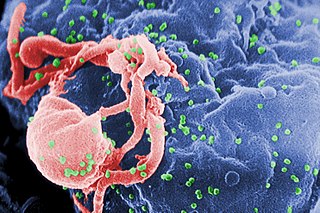

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of Lentivirus that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive. Without treatment, the average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of multiple drugs that act on different viral targets is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HAART decreases the patient's total burden of HIV, maintains function of the immune system, and prevents opportunistic infections that often lead to death. HAART also prevents the transmission of HIV between serodiscordant same-sex and opposite-sex partners so long as the HIV-positive partner maintains an undetectable viral load.

The spread of HIV/AIDS has affected millions of people worldwide; AIDS is considered a pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2016 there were 36.7 million people worldwide living with HIV/AIDS, with 1.8 million new HIV infections per year and 1 million deaths due to AIDS. Misconceptions about HIV and AIDS arise from several different sources, from simple ignorance and misunderstandings about scientific knowledge regarding HIV infections and the cause of AIDS to misinformation propagated by individuals and groups with ideological stances that deny a causative relationship between HIV infection and the development of AIDS. Below is a list and explanations of some common misconceptions and their rebuttals.

AIDS-related lymphoma describes lymphomas occurring in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immune system, an altered microbiome, or breached integumentary barriers. Many of these pathogens do not necessarily cause disease in a healthy host that has a non-compromised immune system, and can, in some cases, act as commensals until the balance of the immune system is disrupted. Opportunistic infections can also be attributed to pathogens which cause mild illness in healthy individuals but lead to more serious illness when given the opportunity to take advantage of an immunocompromised host.

AIDS-defining clinical conditions is the list of diseases published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that are associated with AIDS and used worldwide as a guideline for AIDS diagnosis. CDC exclusively uses the term AIDS-defining clinical conditions, but the other terms remain in common use.

The CDC Classification System for HIV Infection is the medical classification system used by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to classify HIV disease and infection. The system is used to allow the government to handle epidemic statistics and define who receives US government assistance.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a condition seen in some cases of HIV/AIDS or immunosuppression, in which the immune system begins to recover, but then responds to a previously acquired opportunistic infection with an overwhelming inflammatory response that paradoxically makes the symptoms of infection worse.

Virus latency is the ability of a pathogenic virus to lie dormant within a cell, denoted as the lysogenic part of the viral life cycle. A latent viral infection is a type of persistent viral infection which is distinguished from a chronic viral infection. Latency is the phase in certain viruses' life cycles in which, after initial infection, proliferation of virus particles ceases. However, the viral genome is not eradicated. The virus can reactivate and begin producing large amounts of viral progeny without the host becoming reinfected by new outside virus, and stays within the host indefinitely.

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) refers to a condition in which the patient has an elevated temperature (fever) but, despite investigations by one or more qualified physicians, no explanation is found.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. It can be managed with treatment. Without treatment it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Effective treatment for HIV-positive people involves a life-long regimen of medicine to suppress the virus, making the viral load undetectable. There is no vaccine or cure for HIV. An HIV-positive person on treatment can expect to live a normal life, and die with the virus, not of it.

Idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia (ICL) is a rare medical syndrome in which the body has too few CD4+ T lymphocytes, which are a kind of white blood cell. ICL is sometimes characterized as "HIV-negative AIDS", though, in fact, its clinical presentation differs somewhat from that seen with HIV/AIDS. People with ICL have a weakened immune system and are susceptible to opportunistic infections, although the rate of infections is lower than in people with AIDS.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection is a multi-faceted, chronic condition that significantly impacts public health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 2 to 15% of those infected with HIV are also affected by HCV, increasing their risk of morbidity and mortality due to accelerated liver disease. The burden of co-infection is especially high in certain high-risk groups, such as intravenous drug users and men who have sex with men. These individuals who are HIV-positive are commonly co-infected with HCV due to shared routes of transmission including, but not limited to, exposure to HIV-positive blood, sexual intercourse, and passage of the Hepatitis C virus from mother to infant during childbirth.

HIV superinfection is a condition in which a person with an established human immunodeficiency virus infection acquires a second strain of HIV, often of a different subtype. These can form a recombinant strain that co-exists with the strain from the initial infection, as well from reinfection with a new virus strain, and may cause more rapid disease progression or carry multiple resistances to certain HIV medications.

The HIV set point is the viral load or number of virions in the blood of a person infected with HIV. HIV infections are broken down into three stages: acute infection, asymptomatic infection, and AIDS. The acute infection stage refers to the first weeks after infection, where the majority of infected individuals display severe flu-like symptoms such as fever, myalgia, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, and sometimes rash. At this stage, viral loads reach high levels and the number of CD4 helper T cells in the blood begins to drop. At this point, seroconversion, the development of antibodies, occurs and the CD4 T cell counts begin to recover as the immune system attempts to fight the virus, marking the HIV set point. The higher the viral load at the set point, the faster the virus will progress to AIDS; the lower the viral load at the set point, the longer the patient will remain in clinical latency, the next stage of the infection. The asymptomatic or clinical latency phase is marked by slow replication of the HIV virus, followed by steady depletion of CD4 T cells with little to no symptoms. For individuals that are rapid progressors, this phase can be short lived, with an average of 2-3 years. Long-term progressors (LTNPS) can remain stable in this stage for over a decade. An uninfected person has 500-1500 CD4 T cells/μL of blood. When this count lowers to less than 500 CD4 T cells/μL, opportunistic infections can occur where the immune system is no longer able to fight pathogens it would have easily cleared in an unimpaired state. The infection progresses to AIDS when the count falls below 200 CD4 T cells/μL, at which point opportunistic infections can be lethal. At this stage, an infected person has 2-3 years of life expectancy. The use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) can greatly slow the progression of the virus to AIDS. The set point is not completely fixed and constant, but can be quite dynamic with significant fluctuations.

Diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome (DILS) is a rare multi-system complication of HIV believed to occur secondary to an abnormal persistence of the initial CD8+ T cell expansion that regularly occurs in an HIV infection. This persistent CD8+ T cell expansion occurs in the setting of a low CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio and ultimately invades and destroys tissues and organs resulting in the various complications of DILS. DILS classically presents with bilateral salivary gland enlargement (parotitis), cervical lymphadenopathy, and sicca symptoms such as xerophthalmia and xerostomia, but it may also involve the lungs, nervous system, kidneys, liver, digestive tract, and muscles. Once suspected, current diagnostic workups include (1) confirming HIV infection, (2) confirming six or greater months of characteristic signs and symptoms, (3) confirming organ infiltration by CD8+ T cells, and (4) exclusion of other autoimmune conditions. Once the diagnosis of DILS is confirmed, management includes highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and as-needed steroids. With proper treatment, the overall prognosis of DILS is favorable.

AntiViral-HyperActivation Limiting Therapeutics (AV-HALTs) are an investigational class of antiretroviral drugs used to treat Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Unlike other antiretroviral agents given to reduce viral replication, AV-HALTs are single or combination drugs designed to reduce the rate of viral replication while, at the same time, also directly reducing the state of immune system hyperactivation now believed to drive the loss of CD4+ T helper cells leading to disease progression and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

The Berlin patient is an anonymous person from Berlin, Germany, who was described in 1998 as exhibiting prolonged "post-treatment control" of HIV viral load after HIV treatments were interrupted.

HIV/AIDS research includes all medical research that attempts to prevent, treat, or cure HIV/AIDS, as well as fundamental research about the nature of HIV as an infectious agent and AIDS as the disease caused by HIV.

The co-epidemic of tuberculosis (TB) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is one of the major global health challenges in the present time. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that TB is the leading cause of death in those with HIV. In 2019, TB was responsible for 30% of the 690,000 HIV/AIDS related deaths worldwide and 15% of the 1.4 million global TB deaths were in people with HIV or AIDS. The two diseases act in combination as HIV drives a decline in immunity, while tuberculosis progresses due to defective immune status. Having HIV makes one more likely to be infected with tuberculosis, especially if one's CD4 T-cells are low. CD4 T-cells below 200 increases one's risk of tuberculosis infection by 25 times. This condition becomes more severe in case of multi-drug (MDRTB) and extensively drug resistant TB (XDRTB), which are difficult to treat and contribute to increased mortality. Tuberculosis can occur at any stage of HIV infection. The risk and severity of tuberculosis increases soon after infection with HIV. Although tuberculosis can be a relatively early manifestation of HIV infection, it is important to note that the risk of tuberculosis progresses as the CD4 cell count decreases along with the progression of HIV infection. The risk of TB generally remains high in HIV-infected patients, remaining above the background risk of the general population even with effective immune reconstitution and high CD4 cell counts with antiretroviral therapy.