Stalinist repressions may refer to:

Stalinist repressions may refer to:

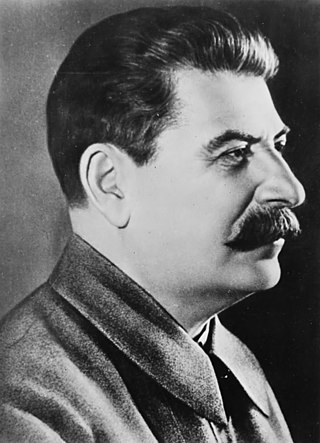

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country, collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality, and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which Stalinism deemed the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time. After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw, a period of de-Stalinization began in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused the influence of Stalin's ideology to begin to wane in the USSR.

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror, also known as the Year of '37 and the Yezhovshchina, was Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin's campaign to consolidate his power over the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Soviet state. The purges also sought to remove the remaining influence of Leon Trotsky. The term great purge, an allusion to the French Revolution's Reign of Terror, was popularized by the historian Robert Conquest in his 1968 book The Great Terror.

Political rehabilitation is the process by which a disgraced member of a political party or a government is restored to public respectability and thus political acceptability. The term is usually applied to leaders or other prominent individuals who regain their prominence after a period in which they have no influence or standing, including deceased people who are vindicated posthumously. Historically, the concept is usually associated with Communist states and parties where, as a result of shifting political lines often as part of a power struggle, leading members of the Communist Party find themselves on the losing side of a political conflict and out of favour, often to the point of being denounced, imprisoned or even executed.

Hilary Minc was a Polish economist and communist politician prominent in Stalinist Poland.

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, tens of millions of people suffered political repression, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution. It culminated during the Stalin era, then declined, but it continued to exist during the "Khrushchev Thaw", followed by increased persecution of Soviet dissidents during the Brezhnev era, and it did not cease to exist until late in Mikhail Gorbachev's rule when it was ended in keeping with his policies of glasnost and perestroika.

Anti-Sovietism or anti-Soviet sentiment refers to persons and activities that were actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the Soviet Union.

Neo-Stalinism is the promotion of positive views of Joseph Stalin's role in history, the partial re-establishing of Stalin's policies on certain or all issues, and nostalgia for the Stalinist period. Neo-Stalinism overlaps significantly with neo-Sovietism and Soviet nostalgia. Various definitions of the term have been given over the years.

The Soviet deportations from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina took place between late 1940 and 1951 and were part of Joseph Stalin's policy of political repression of the potential opposition to the Soviet power. The deported were typically moved to so-called "special settlements" (спецпоселения).

Europe: A History is a 1996 narrative history book by Norman Davies.

The Stalinist repressions in Mongolia was an 18-month period of heightened political violence and persecution in the Mongolian People's Republic between 1937 and 1939. The repressions were an extension of the Stalinist purges unfolding across the Soviet Union around the same time. Soviet NKVD advisors, under the nominal direction of Mongolia's de facto leader Khorloogiin Choibalsan, persecuted thousands of individuals and organizations perceived as threats to the Mongolian revolution and the growing Soviet influence in the country. As in the Soviet Union, methods of repression included torture, show trials, executions, and imprisonment in remote forced labor camps, often in Soviet gulags. Estimates differ, but anywhere between 20,000 and 35,000 "enemies of the revolution" were executed, a figure representing three to five percent of Mongolia's total population at the time. Victims included those accused of espousing Tibetan Buddhism, pan-Mongolist nationalism, and pro-Japanese sentiment. Buddhist clergy, aristocrats, intelligentsia, political dissidents, and ethnic Buryats and Kazakhs suffered the greatest losses.

In the terminology of communist states and Marxism–Leninism, the general line of the party or simply the general line is the directives of the governing bodies of a party which define the party's politics. The term was in common use by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and also adopted by many other communist parties around the world. The notion is rooted in the major principle of democratic centralism, which requires unconditional obedience to collective decisions.

Roman Romkowski born Nasiek (Natan) Grinszpan-Kikiel, was a Polish communist official trained by Comintern in Moscow. After the Soviet takeover of Poland Romkowski settled in Warsaw and became second in command in the Ministry of Public Security during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Along with several other high functionaries including Stanisław Radkiewicz, Anatol Fejgin, Józef Różański, Julia Brystiger and the chief supervisor of Polish State Security Services, Minister Jakub Berman from the Politburo, Romkowski came to symbolize communist terror in postwar Poland. He was responsible for the work of departments: Counter-espionage (1st), Espionage (7th), Security in the PPR–PZPR, and others.

Ideological repression in the Soviet Union targeted various worldviews and the corresponding categories of people.

The Train of Pain – Memorial to Victims of Stalinist Repression is a monument in Chișinău, Moldova. A temporary stone was unveiled in 1990 in Central Station Square commemorating the 1940–1951 mass deportations in Soviet Moldavia. A permanent memorial was completed at the site in 2013. The sculptural element was assembled in Belarus.

Some historians and other authors have carried out comparisons of Nazism and Stalinism. They have considered the similarities and differences between the two ideologies and political systems, the relationship between the two regimes, and why both came to prominence simultaneously. During the 20th century, the comparison of Nazism and Stalinism was made on totalitarianism, ideology, and personality cult. Both regimes were seen in contrast to the liberal democratic Western world, emphasising the similarities between the two.

The anti-Stalinist left is a term that refers to various kinds of Marxist political movements that oppose Joseph Stalin, Stalinism, Neo-Stalinism and the system of governance that Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union between 1924 and 1953. This term also refers to the high ranking political figures and governmental programs that opposed Joseph Stalin and his form of communism, such as Leon Trotsky and other traditional Marxists within the Left Opposition.

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable to the Soviet revolutionary and dictator Joseph Stalin vary widely. The scholarly consensus affirms that archival materials declassified in 1991 contain irrefutable data far superior to sources used prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants.

The Victims of Communism Memorial is a memorial in Washington, D.C. It may also refer to:

Victims of Stalinism is a topic of disagreement among scholars of Communism. It may also refer to:

Akhundzade is an Azerbaijani surname. Notable people with the surname include: