Local boards or local boards of health were local authorities in urban areas of England and Wales from 1848 to 1894. They were formed in response to cholera epidemics and were given powers to control sewers, clean the streets, regulate environmental health risks including slaughterhouses and ensure the proper supply of water to their districts. Local boards were eventually merged with the corporations of municipal boroughs in 1873, or became urban districts in 1894.

Joseph Milner Wightman was an American politician who, from 1861 to 1863, served as the seventeenth Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts.

Sarah "Annie" Turner Wittenmyer was an American social reformer, relief worker, and writer. She served as the first President of the Women's Christian Temperance Union from 1874 to 1879. The Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home was renamed the Annie Wittenmyer Home in 1949 in her honor.

Margaret Abigail Cleaves, M.D., was an American physician and scientific writer. She was a pioneer of electrotherapy and brachytherapy, instructor in Electro-Therapeutics New York Post-Graduate Medical School, President of the Women's Medical Society of New York, a Fellow of the American Electro-Therapeutic Association, a member of the Société Francaise d'Electrothérapie, a Fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine, Editor of Asylum Notes: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1891-2, a member of the Medical Society of the County of New York, a member of the American Medical Association, and a member of the New York Electrical Society.

Tullio Antonio Rottanzi (1867–1911) was an American physician who served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in the late 19th century and was noted for introducing a law that banned the wearing of tall hats in theaters. As a short-term acting mayor he sought out ways of cutting indolence and waste in city government, and during a city crisis in which two boards of supervisors claimed to hold power, he was the only person serving on both bodies.

Sadie American was a Jewish-American activist, social worker, activist, and "Chicago's pioneer of visual sociology".

Verina Harris Morton Jones was an American physician, suffragist and clubwoman. Following her graduation from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1888 she was the first woman licensed to practice medicine in Mississippi. She then moved to Brooklyn where she co-founded and led the Lincoln Settlement House. Jones was involved with numerous civic and activist organizations and was elected to the board of directors of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

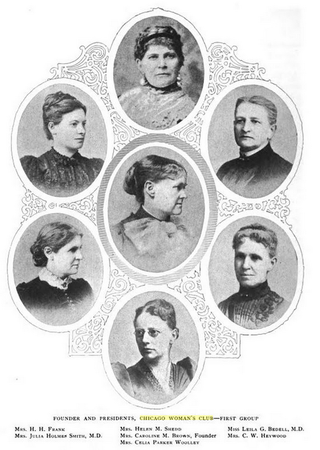

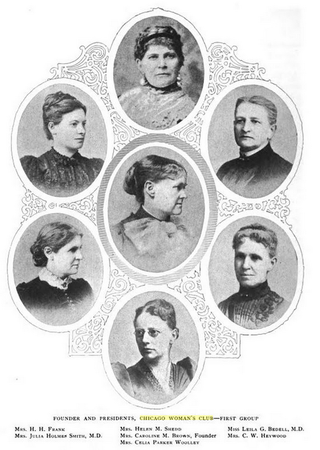

The Chicago Woman's Club was formed in 1876 by women in Chicago who were interested in "self and social improvement." The club was notable for creating educational opportunities in the Chicago region and helped create the first juvenile court in the United States. The group was primarily made up of wealthy and middle-class white women, with physicians, lawyers and university professors playing "prominent roles." The club often worked towards social and educational reform in Chicago. It also hosted talks by prominent women, including artists and suffragists.

Mary Towne Burt was a 19th-century American temperance reformer, newspaper publisher, and benefactor from Ohio. Burt was identified with temperance work nearly all her life. She was the first president of the Auburn, New York branch of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and beginning in 1882, served as president of the New York State Society of the Union. In 1875, she became the publisher, and subsequently the editor, of Our Union, the organ of the society, and in 1878–80 was the corresponding secretary of the National Union. For several years, Burt had charge of the legislative interests of the union, and several laws for the protection of women and young girls resulted from her efforts.

Harriet Abbott Lincoln Coolidge was an American philanthropist, author and reformer. She did much in the way of instructing young mothers in the care and clothing of infants, and furthered the cause to improve the condition of infants in foundling hospitals. She contributed a variety of articles on kindergarten matters to the daily press, and while living in Washington, D.C., she gave a series of "nursery talks" for mothers at her home, where she fitted up a model nursery. Coolidge was the editor of Trained Motherhood; and author of In the Story Land, Kindergarten Stories, Talks to Mothers, The Model Nursery, and What a Young Girl Ought to Know. She was one of the original signers of the Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and was an active member of four of the leading charity organizations in Washington. She died in 1902.

Ella M. S. Marble was an American physician who worked as a journalist, educator, and activist earlier in her career. From girlhood, she took an active interest in any movement calculated to advance the interests of women. Interested in literary and philanthropic work, Marble served as president of the District of Columbia Federation Womans' Clubs, numbering ten societies and 2,500 members ; president, District Federal; vice-president, Womans' National Press Association for state of Maine; president, Minnesota State Suffrage Association; president, Minneapolis City Suffrage Association; president, Washington City Suffrage Association; Secretary, Pro Re Noto; and secretary, White Cross Society of Minneapolis.

Jennie McCowen was an American physician, writer, and medical journal editor. She lectured on and supported woman's suffrage.

Socialhousekeeping, also known as municipal or civil housekeeping, was a socio-political movement that occurred primarily through the 1880s to the early 1900s in the Progressive Era around the United States.

Rosalie Loew Whitney was an American lawyer and suffragist.

Nettie Sanford Chapin was a 19th-century American teacher, historian, author, newspaper publisher, suffragist, and activist. Chapin wrote mostly prose. She also wrote on Iowa history, and published several small books herself. While residing at Washington, D.C. for several winters, she wrote concerning society and fashionable Washington circles. In 1875, she began the publication of The Ladies Bureau, the first newspaper published west of Chicago by a woman. Chapin served as chair of the National Committee of the National Equal Rights Party.

Elmina M. Roys Gavitt was an American physician. She was also the founder and first editor of The Woman's Medical Journal, the first scientific monthly journal published to forward the interests exclusively of women physicians.

Margaret McDonald Bottome was an American reformer, organizational founder, and author. She was engaged in religious work in Brooklyn, and for more than a quarter of a century, she gave Bible talks to the society women of New York City. Out of these experiences grew the order of the King's Daughters, which she founded and for which she was annually chosen president until her death. She was the author of several books, and made a large number of contributions to religious magazines.

Louise M. Harvey Clarke (1859-1934) was a medical doctor and widely known writer, speaker, and clubwoman in Los Angeles and Riverside counties, California.

Whittier House was an American social settlement, situated in the midst of the densely populated Paulus Hook district of Jersey City, New Jersey. Christian, but non-denominational, its aims were to help all in need by improving their circumstances, by inspiring them with new motives and higher ideals, and by making them better fitted by the responsibilities and privileges of life. It cooperated with all who were seeking to ameliorate the human condition and improve the social order. It opened in the People's Palace, December 20, 1893. On May 14, 1894, it incorporated and moved to 174 Grand Street.