Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period (春秋) and Warring States period (戰國時期), during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begun in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years. Some can be found in the I Ching, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE.

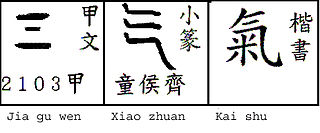

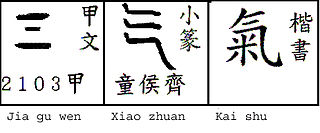

In traditional Chinese culture and the East Asian cultural sphere, qi, also ki or chi in Wade–Giles romanization, is believed to be a vital force forming part of any living entity. Literally meaning "vapor", "air", or "breath", the word qi is often translated as "vital energy", "vital force", "material energy", or simply as "energy". Qi is the central underlying principle in Chinese traditional medicine and in Chinese martial arts. The practice of cultivating and balancing qi is called qigong.

Zhu Xi, formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He contributed greatly to Chinese philosophy and fundamentally reshaped the Chinese worldview. His works include his editing of and commentaries to the Four Books, his writings on the process of the "investigation of things", and his development of meditation as a method for self-cultivation.

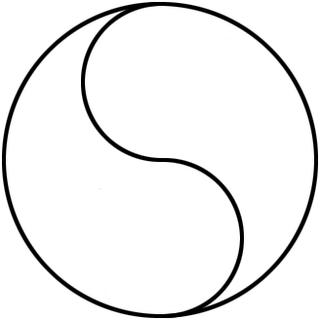

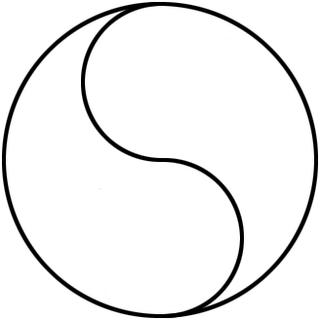

In Chinese philosophy, Taiji or Tai chi is a cosmological term for the "Supreme Ultimate" state of the world and affairs - the interaction of matter and space, the relation of the body and mind. While Wuji is undifferentiated, timeless, absolute, infinite potential -- Taiji is differentiated, dualistic, and relative. Yin and Yang originate from Wuji to become Taiji. Compared with Wuji, Taiji describes movement and change wherein limits do arise. Wuji is often translated "no pole". Taiji is often translated "polar", with polarity, revealing opposing features as in hot/cold, up/down, dry/wet, day/night.

The zàng-fǔ organs are functional entities stipulated by traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). They constitute the centrepiece of TCM's general concept of how the human body works. The term zàng (脏) refers to the organs considered to be yin in nature – Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung, Kidney – while fǔ (腑) refers to the yang organs – Small Intestine, Large Intestine, Gall Bladder, Urinary Bladder, Stomach and Sānjiaō.

According to traditional Chinese medicine, the kidney refers to either of the two viscera located on the small of the back, one either side of the spine. As distinct from the Western medical definition of kidneys, the TCM concept is more a way of describing a set of interrelated parts than an anatomical organ. In TCM the kidneys are associated with "the gate of Vitality" or "Ming Men". A famous Chinese doctor named Zhang Jie Bin wrote "there are two kidneys,, with the Gate of Vitality between them. The kidney is the organ of water and fire, the abode of yin and yang, the sea of essence, and it determines life and death."

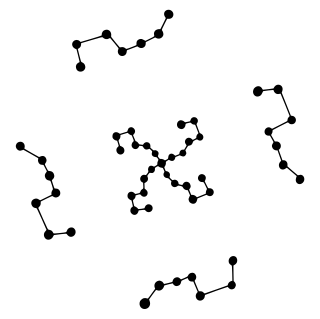

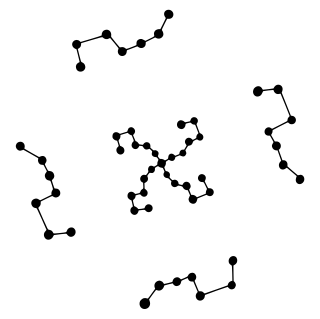

The bagua or pakua (八卦) are a set of eight symbols that originated in China, used in Taoist cosmology to represent the fundamental principles of reality, seen as a range of eight interrelated concepts. Each consists of three lines, each line either "broken" or "unbroken", respectively representing yin or yang. Due to their tripartite structure, they are often referred to as Eight Trigrams in English.

Zhang Zai (1020–1077) was a Chinese philosopher and politician. He is most known for laying out four ontological goals for intellectuals: to build up the manifestations of Heaven and Earth's spirit, to build up good life for the populace, to develop past sages' endangered scholarship, and to open up eternal peace.

Zhou Dunyi was a Chinese cosmologist, philosopher, and writer during the Song dynasty. He conceptualized the Neo-Confucian cosmology of the day, explaining the relationship between human conduct and universal forces. In this way, he emphasizes that humans can master their qi ("spirit") in order to accord with nature. He was a major influence to Zhu Xi, who was the architect of Neo-Confucianism. Zhou Dunyi was mainly concerned with Taiji and Wuji, the yin and yang, and the wu xing. He is also venerated and credited in Taoism as the first philosopher to popularize the concept of the taijitu or "yin-yang symbol".

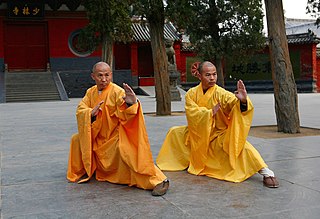

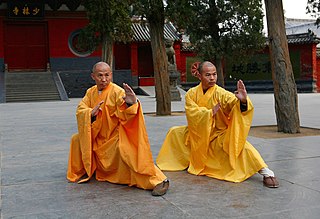

Neigong, also spelled nei kung, neigung, or nae gong, refers to any of a set of Chinese breathing, meditation, somatics practices, and spiritual practice disciplines associated with Daoism and especially the Chinese martial arts. Neigong practice is normally associated with the so-called "soft style", "internal" or neijia 內家 Chinese martial arts, as opposed to the category known as waigong 外功 or "external skill" which is historically associated with shaolinquan or the so-called "hard style", "external" or wàijiā 外家 Chinese martial arts. Both have many different schools, disciplines and practices and historically there has been mutual influence between the two and distinguishing precisely between them differs from school to school.

In Chinese martial arts, there are fighting styles that are modeled after animals.

Lu Jiuyuan, or Lu Xiangshan, was a Chinese philosopher and writer who founded the school of the universal mind, the second most influential Neo-Confucian school. He was a contemporary and the main rival of Zhu Xi.

Chinese creation myths are symbolic narratives about the origins of the universe, earth, and life. In Chinese mythology, the term "cosmogonic myth" or "origin myth" is more accurate than "creation myth", since very few stories involve a creator deity or divine will. Chinese creation myths fundamentally differ from monotheistic traditions with one authorized version, such as the Judeo-Christian Genesis creation narrative: Chinese classics record numerous and contradictory origin myths. Traditionally, the world was created on Chinese New Year and the animals, people, and many deities were created during its 15 days.

The Cantong qi is deemed to be the earliest book on alchemy in China. The title has been variously translated as Kinship of the Three, Akinness of the Three, Triplex Unity, The Seal of the Unity of the Three, and in several other ways. The full title of the text is Zhouyi cantong qi, which can be translated as, for example, The Kinship of the Three, in Accordance with the Book of Changes.

The Pagoda of Bailin Temple, is located in Zhao County, Hebei. It is an octagonal-based brick Chinese pagoda built in 1330 during the reign of Emperor Wenzong, ruler of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty.

Bianhua meaning "transformation, metamorphosis" was a keyword in both Daoism and Chinese Buddhism. Daoists used bianhua describing things transforming from one type to another, such as from a caterpillar to a butterfly. Buddhist translators used bianhua for Sanskrit nirmāṇa "manifest through transformations", such as the nirmāṇa-kaya "transformation body" of a Buddha's reincarnations.

Chinese theology, which comes in different interpretations according to the classic texts and the common religion, and specifically Confucian, Taoist, and other philosophical formulations, is fundamentally monistic, that is to say it sees the world and the gods of its phenomena as an organic whole, or cosmos, which continuously emerges from a simple principle. This is expressed by the concept that "all things have one and the same principle". This principle is commonly referred to as Tiān 天, a concept generally translated as "Heaven", referring to the northern culmen and starry vault of the skies and its natural laws which regulate earthly phenomena and generate beings as their progenitors. Ancestors are therefore regarded as the equivalent of Heaven within human society, and therefore as the means connecting back to Heaven which is the "utmost ancestral father". Chinese theology may be also called Tiānxué 天學, a term already in use in the 17th and 18th centuries.

[In contrast to the God of Western religions who is above the space and time] the God of Fuxi, Xuanyuan, and Wang Yangming is under in our space and time. ... To Chinese thought, ancestor is creator.

The c. 350 BCE Neiye 內業 or Inward Training is the oldest Chinese received text describing Daoist breath meditation techniques and qi circulation. After the Guanzi, a political and philosophical compendium, included the Neiye around the 2nd century BCE, it was seldom mentioned by Chinese scholars until the 20th century, when it was reevaluated as a "proto-Daoist" text that clearly influenced the Daode jing, Zhuangzi, and other classics. Neiye traditions also influenced Chinese thought and culture. For instance, it had the first references to cultivating the life forces jing "essence", qi "vital energy", and shen "spirit", which later became a fundamental concept in Daoist Neidan "internal alchemy", as well as the Three Treasures in traditional Chinese medicine.

In Confucianism, the Sangang Wuchang, sometimes translated as the Three Fundamental Bonds and Five Constant Virtues or the Three Guiding Principles and Five Constant Regulations, or more simply "bonds and virtues", are the three most important human relationships and the five most important virtues. They are considered the moral and political requirements of Confucianism as well as the eternal unchanging "essence of life and bonds of society."