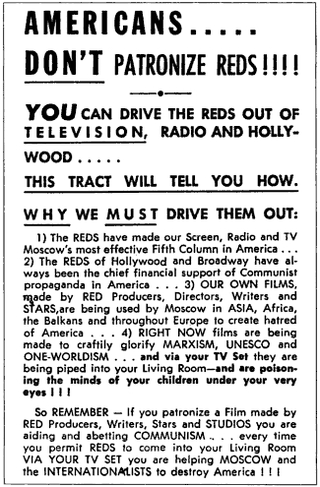

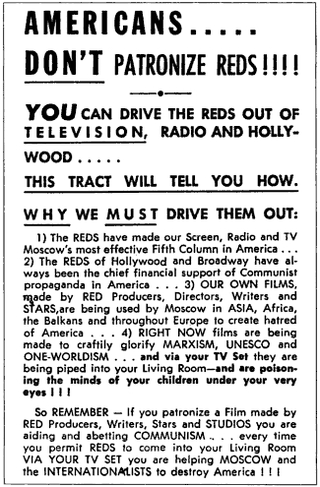

McCarthyism, also known as the second Red Scare, was the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a campaign spreading fear of alleged communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage in the United States during the late 1940s through the 1950s. After the mid-1950s, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, who had spearheaded the campaign, gradually lost his public popularity and credibility after several of his accusations were found to be false. The U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren made a series of rulings on civil and political rights that overturned several key laws and legislative directives, and helped bring an end to the Second Red Scare. Historians have suggested since the 1980s that as McCarthy's involvement was less central than that of others, a different and more accurate term should be used instead that more accurately conveys the breadth of the phenomenon, and that the term McCarthyism is now outdated. Ellen Schrecker has suggested that Hooverism after FBI Head J. Edgar Hoover is more appropriate.

National Review is an American conservative-right-libertarian editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich Lowry, and its editor is Ramesh Ponnuru.

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, right-wing populist, and right-wing libertarian ideas. Originally based in Belmont, Massachusetts, the JBS is now headquartered in Grand Chute, Wisconsin, with local chapters throughout the United States. It owns American Opinion Publishing, Inc., which publishes the magazine The New American, and it is affiliated with an online school called FreedomProject Academy.

Phyllis Stewart Schlafly was an American attorney, conservative activist, author, and anti-feminist spokesperson for the national conservative movement. She held paleoconservative social and political views, opposed feminism, gay rights and abortion, and successfully campaigned against ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) is a conservative youth activism organization that was founded in 1960 as a coalition between traditional conservatives and libertarians on American college campuses. It is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and the chapter affiliate of Young America's Foundation. The purposes of YAF are to advocate public policies consistent with the Sharon Statement, which was adopted by young conservatives at a meeting at the home of William F. Buckley in Sharon, Connecticut, on September 11, 1960.

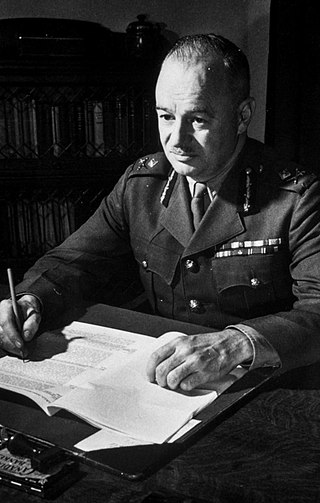

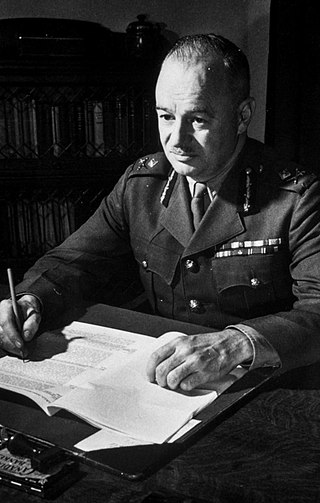

George Brock Chisholm was a Canadian psychiatrist, medical practitioner, World War I veteran, and the first director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO). He was the 13th Canadian Surgeon General and the recipient of numerous accolades, including Order of Canada, Order of the British Empire, Military Cross, and Efficiency Decoration.

The Cornell Review is an independent newspaper published by students of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. With the motto, "We Do Not Apologize," the Review has a history in conservative journalism and was once one of the leading college conservative publications in the United States. While the ideological makeup of its staff shifts over the years, the paper has consistently accused Cornell of adhering to left-wing politics and political correctness, delivered with a signature anti-establishment tone.

Robert Henry Winborne Welch Jr. was an American businessman, political organizer, and conspiracy theorist. He was wealthy following his retirement from the candy business and used his wealth to sponsor anti-communist causes. He co-founded the John Birch Society (JBS), an American extreme right-wing political advocacy group, in 1958 and tightly controlled it until his death. He was highly controversial and criticized by liberals, as well as some conservatives, including William F. Buckley Jr, only after being an early donor to Buckley’s National Review in the 1950s.

In the United States, conservatism is based on a belief in limited government, individualism, traditionalism, republicanism, and limited federal governmental power in relation to U.S. states. Conservative and Christian media organizations, along with American conservative figures, are influential, and American conservatism is one of the majority political ideologies within the Republican Party.

The United States anti-abortion movement contains elements opposing induced abortion on both moral and religious grounds and supports its legal prohibition or restriction. Advocates generally argue that human life begins at conception and that the human zygote, embryo or fetus is a person and therefore has a right to life. The anti-abortion movement includes a variety of organizations, with no single centralized decision-making body. There are diverse arguments and rationales for the anti-abortion stance. Some anti-abortion activists allow for some permissible abortions, including therapeutic abortions, in exceptional circumstances such as incest, rape, severe fetal defects, or when the woman's health is at risk.

Brain-Washing: A Synthesis of the Russian Textbook on Psychopolitics is a Red Scare, black propaganda book, published by the Church of Scientology in 1955 about brainwashing. L. Ron Hubbard authored the text and alleged it was the secret manual written by Lavrentiy Beria, the Soviet secret police chief, in 1936. In this text, many of the practices Scientology opposes are described as Communist-led conspiracies, and its technical content is limited to suggesting more of these practices on behalf of the Soviet Union. The text also describes the Church of Scientology as the greatest threat to Communism.

The Minute Women of the U.S.A. was one of the largest of a number of anti-Communist women's groups that were active during the 1950s and early 1960s. Such groups, which organized American suburban housewives into anti-Communist study groups, political activism and letter-writing campaigns, were a bedrock of support for McCarthyism.

The Alaska Mental Health Enabling Act of 1956 was an Act of Congress passed to improve mental health care in the United States territory of Alaska. It became the focus of a major political controversy after opponents nicknamed it the "Siberia Bill" and denounced it as being part of a communist plot to hospitalize and brainwash Americans. Campaigners asserted that it was part of an international Jewish, Roman Catholic or psychiatric conspiracy intended to establish United Nations-run concentration camps in the United States.

Michelle Eunjoo Steel is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for California's 45th congressional district since 2023, previously representing the 48th congressional district from 2021 to 2023. A member of the Republican Party, she concurrently served as a member of House Minority Whip Steve Scalise's Whip Team for the 117th Congress.

Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America is a 501(c)(4) non-profit organization that seeks to reduce and ultimately end abortion in the U.S. by supporting anti-abortion politicians, primarily women, through its SBA List Candidate Fund political action committee.

Movement conservatism is a term used by political analysts to describe conservatives in the United States since the mid-20th century and the New Right. According to George H. Nash (2009) the movement comprises a coalition of five distinct impulses. From the mid-1930s to the 1960s, libertarians, traditionalists, and anti-communists made up this coalition, with the goal of fighting the liberals' New Deal. In the 1970s, two more impulses were added with the addition of neoconservatives and the religious right.

In the politics of the United States, the radical right is a political preference that leans towards ultraconservatism, white nationalism, white supremacy, or other far-right ideologies in a hierarchical structure which is paired with conspiratorial rhetoric alongside traditionalist and reactionary aspirations. The term was first used by social scientists in the 1950s regarding small groups such as the John Birch Society in the United States, and since then it has been applied to similar groups worldwide. The term "radical" was applied to the groups because they sought to make fundamental changes within institutions and remove persons and institutions that threatened their values or economic interests from political life.

This timeline of modern American conservatism lists important events, developments and occurrences which have significantly affected conservatism in the United States. With the decline of the conservative wing of the Democratic Party after 1960, the movement is most closely associated with the Republican Party (GOP). Economic conservatives favor less government regulation, lower taxes and weaker labor unions while social conservatives focus on moral issues and neoconservatives focus on democracy worldwide. Conservatives generally distrust the United Nations and Europe and apart from the libertarian wing favor a strong military and give enthusiastic support to Israel.

Women in conservatism in the United States have advocated for social, political, economic, and cultural conservative policies since anti-suffragism. Leading conservative women such as Phyllis Schlafly have expressed that women should embrace their privileged essential nature. This thread of belief can be traced through the anti-suffrage movement, the Red Scare, and the Reagan Era, and is still present in the 21st century, especially in several conservative women's organizations such as Concerned Women for America and the Independent Women's Forum.

There has never been a national political party in the United States called the Conservative Party. All major American political parties support republicanism and the basic classical liberal ideals on which the country was founded in 1776, emphasizing liberty, the pursuit of happiness, the rule of law, the consent of the governed, opposition to aristocracy and fear of corruption, coupled with equal rights before the law. Political divisions inside the United States often seemed minor or trivial to Europeans, where the divide between the Left and the Right led to violent political polarization, starting with the French Revolution.