The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans within that were ethnically cleansed by the United States government.

Manifest destiny was a phrase in the 19th-century United States that represented the belief that American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("manifest") and certain ("destiny"). The belief was rooted in American exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism, implying the inevitable spread of the Republican form of governance. It was one of the earliest expressions of American imperialism in the United States of America.

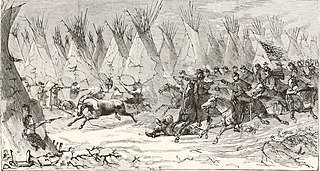

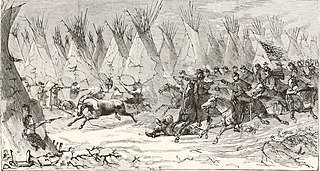

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi". During the presidency of Jackson (1829–1837) and his successor Martin Van Buren (1837–1841) more than 60,000 Native Americans from at least 18 tribes were forced to move west of the Mississippi River where they were allocated new lands. The southern tribes were resettled mostly in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The northern tribes were resettled initially in Kansas. With a few exceptions, the United States east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes was emptied of its Native American population. The movement westward of indigenous tribes was characterized by a large number of deaths occasioned by the hardships of the journey.

Population figures for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization have been difficult to establish. By the end of the 20th century, most scholars gravitated toward an estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is an American historian, writer, professor, and activist based in San Francisco. Born in Texas, she grew up in Oklahoma and is a social justice and feminist activist. She has written numerous books including Blood on the Border: A Memoir of the Contra Years (2005), Red Dirt: Growing up Okie (1992), and An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States (2014). She is professor emeritus in Ethnic Studies at California State University.

The discovery doctrine, or doctrine of discovery, is a disputed interpretation of international law during the Age of Discovery, introduced into United States municipal law by the US Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in Johnson v. McIntosh (1823). In Marshall's formulation of the doctrine, discovery of territory previously unknown to Europeans gave the discovering nation title to that territory against all other European nations, and this title could be perfected by possession. A number of legal scholars have criticized Marshall's interpretation of the relevant international law. In recent decades, advocates for Indigenous rights have campaigned against the doctrine. In 2023, the Vatican formally repudiated the doctrine.

The genocide of Indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is the intentional elimination of Indigenous peoples as a part of the process of colonialism.

The history of Native Americans in the United States began before the founding of the country, tens of thousands of years ago with the settlement of the Americas by the Paleo-Indians. Anthropologists and archeologists have identified and studied a wide variety of cultures that existed during this era. Their subsequent contact with Europeans had a profound impact on their history afterwards.

Settler colonialism occurs when colonizers invade and occupy territory to permanently replace the existing society with the society of the colonizers.

Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment is a book written by the historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and published by City Lights Books. It takes a close and unexpected look at the historical origins of the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution. Despite being no fan of guns, Dunbar approaches the subject from neither the liberal nor the conservative side of the usual debate, instead digging deeply into the subject as a historian to unearth surprising facts.

The connection between colonialism and genocide has been explored in academic research. According to historian Patrick Wolfe, "[t]he question of genocide is never far from discussions of settler colonialism." Historians have commented that although colonialism does not necessarily directly involve genocide, research suggests that the two share a connection.

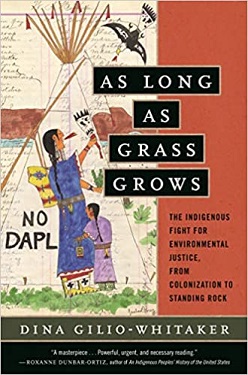

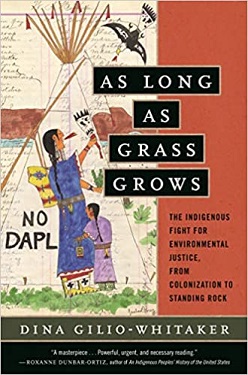

As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock is a 2019 non-fiction book by Dina Gilio-Whitaker. The author details the history of Native Americans in the United States since European colonization, including criticisms of the modern conservation movement as exclusionary to indigenous concepts of land and environmental stewardship, and coverage of the 2010s Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker is an American academic, journalist and author, who studies Native Americans in the United States, decolonization and environmental justice. She is a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. In 2019, she published As Long as Grass Grows.

American Holocaust: Columbus and the Conquest of the New World is a multidisciplinary book about the indigenous peoples of the Americas and colonial history written by American scholar and historian David Stannard.

The Apocalypse of Settler Colonialism: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, and Capitalism in 17th Century North America and the Caribbean is a book by Gerald Horne. It is a historical analysis of the development of settler colonialism in North America and the Caribbean in the 17th century. Sarah Barber from the Lancaster University Department of History reviews the book and concludes "Writing accessible history is never easy, and this is a laudable addition." David Waldstreicher, Professor of History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, British colonizers committed counter-revolution—revolting against crown and against the threat from below—to increase their control over land and people.

Denial of genocides of Indigenous peoples consists of a claim that has denied any of the multiple genocides and atrocity crimes, which have been committed against Indigenous peoples. The denialism claim contradicts the academic consensus, which acknowledges that genocide was committed. The claim is a form of denialism, genocide denial, historical negationism and historical revisionism. The atrocity crimes include genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing.

The Dawning of the Apocalypse: The Roots of Slavery, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, and Capitalism in the Long Sixteenth Century is a book by Gerald Horne, a Professor of African American History at the University of Houston. The book offers a historical analysis of the development of settler colonialism in North America in the 16th century.

Indigenous response to colonialism has varied depending on the Indigenous group, historical period, territory, and colonial state(s) they have interacted with. Indigenous peoples have had agency in their response to colonialism. They have employed armed resistance, diplomacy, and legal procedures. Others have fled to inhospitable, undesirable or remote territories to avoid conflict. Nevertheless, some Indigenous peoples were forced to move to reservations or reductions, and work in mines, plantations, construction, and domestic tasks. They have detribalized and culturally assimilated into colonial societies. On occasion, Indigenous peoples have formed alliances with one or more Indigenous or non-Indigenous nations. Overall, the response of Indigenous peoples to colonialism during this period has been diverse and varied in its effectiveness. Indigenous resistance has a centuries-long history that is complex and carries on into contemporary times.

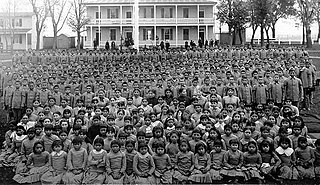

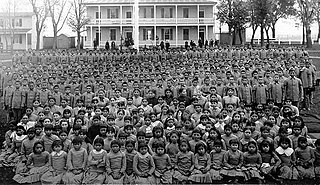

Both during and after the colonial era in American history, white settlers engaged in prolonged conflicts with Native Americans in the United States, seeking to displace them and seize their lands, resulting in Native American enslavement and forced assimilation into settler culture. The 19th century witnessed a surge in efforts to forcibly remove certain Native American nations, while those who remained faced systemic racism at the hands of the federal government. Ideologies like Manifest destiny justified the violent expansion westward, leading to the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and armed clashes.

The destruction of Native American peoples, cultures, and languages of has been characterized as a form of genocide. The question of whether this event constitutes genocide is debated amongst scholars. Debates are ongoing over whether the entire process, or specific periods and local occurrences, meet the legal definition of genocide. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term "genocide", considered the displacement of Native Americans by European settlers as a historical example of genocide. However, others, like historian Gary Anderson, contend that genocide does not accurately characterize any aspect of American history, suggesting instead that ethnic cleansing is a more appropriate term.