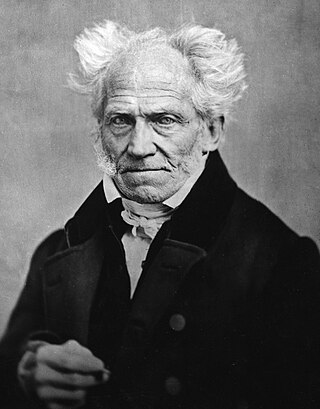

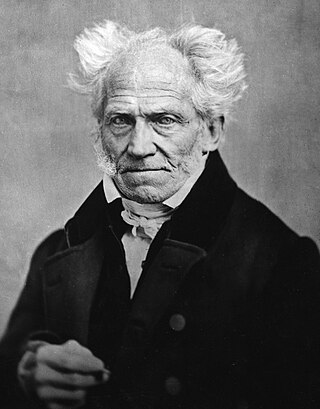

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation, which characterizes the phenomenal world as the product of a blind noumenal will. Building on the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Schopenhauer developed an atheistic metaphysical and ethical system that rejected the contemporaneous ideas of German idealism. He was among the first thinkers in Western philosophy to share and affirm significant tenets of Indian philosophy, such as asceticism, denial of the self, and the notion of the world-as-appearance. His work has been described as an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism.

The meaning of life, or the answer to the question: "What is the meaning of life?", pertains to the significance of living or existence in general. Many other related questions include: "Why are we here?", "What is life all about?", or "What is the purpose of existence?" There have been many proposed answers to these questions from many different cultural and ideological backgrounds. The search for life's meaning has produced much philosophical, scientific, theological, and metaphysical speculation throughout history. Different people and cultures believe different things for the answer to this question.

The five precepts or five rules of training is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay people. They constitute the basic code of ethics to be respected by lay followers of Buddhism. The precepts are commitments to abstain from killing living beings, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying and intoxication. Within the Buddhist doctrine, they are meant to develop mind and character to make progress on the path to enlightenment. They are sometimes referred to as the Śrāvakayāna precepts in the Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the bodhisattva precepts. The five precepts form the basis of several parts of Buddhist doctrine, both lay and monastic. With regard to their fundamental role in Buddhist ethics, they have been compared with the ten commandments in Abrahamic religions or the ethical codes of Confucianism. The precepts have been connected with utilitarianist, deontological and virtue approaches to ethics, though by 2017, such categorization by western terminology had mostly been abandoned by scholars. The precepts have been compared with human rights because of their universal nature, and some scholars argue they can complement the concept of human rights.

Speciesism is a term used in philosophy regarding the treatment of individuals of different species. The term has several different definitions within the relevant literature. A common element of most definitions is that speciesism involves treating members of one species as morally more important than members of other species in the context of their similar interests. Some sources specifically define speciesism as discrimination or unjustified treatment based on an individual's species membership, while other sources define it as differential treatment without regard to whether the treatment is justified or not. Richard Ryder, who coined the term, defined it as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favour of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species." Speciesism results in the belief that humans have the right to use non-human animals, which scholars say is pervasive in the modern society. Studies increasingly suggest that people who support animal exploitation also tend to endorse racist, sexist, and other prejudicial views, which furthers the beliefs in human supremacy and group dominance to justify systems of inequality and oppression.

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that refers to the (universal) Self or self-existent essence of individuals, as distinct from ego (Ahamkara), mind (Citta) and embodied existence (Prakṛti). The term is often translated as soul, but is better translated as "Self," as it solely refers to pure consciousness or witness-consciousness, beyond identification with phenomena. In order to attain moksha (liberation), a human being must acquire self-knowledge.

This Index of ethics articles puts articles relevant to well-known ethical debates and decisions in one place - including practical problems long known in philosophy, and the more abstract subjects in law, politics, and some professions and sciences. It lists also those core concepts essential to understanding ethics as applied in various religions, some movements derived from religions, and religions discussed as if they were a theory of ethics making no special claim to divine status.

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Vedas as a valid source of knowledge; whether the school believes in the premises of Brahman and Atman; and whether the school believes in afterlife and Devas.

Ethics involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior. A central aspect of ethics is "the good life", the life worth living or life that is simply satisfying, which is held by many philosophers to be more important than traditional moral conduct.

The practice of vegetarianism is strongly linked with a number of religious traditions worldwide. These include religions that originated in India, such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. With close to 85% of India's billion-plus population practicing these religions, India remains the country with the highest number of vegetarians in the world.

Buddhist vegetarianism is the practice of vegetarianism by significant portions of Mahayana Buddhist monks and nuns and some Buddhists of other sects. In Buddhism, the views on vegetarianism vary between different schools of thought. The Mahayana schools generally recommend a vegetarian diet because they claimed Gautama Buddha set forth in some of the sutras that his followers must not eat the flesh of any sentient being.

Buddhist ethics are traditionally based on what Buddhists view as the enlightened perspective of the Buddha. The term for ethics or morality used in Buddhism is Śīla or sīla (Pāli). Śīla in Buddhism is one of three sections of the Noble Eightfold Path, and is a code of conduct that embraces a commitment to harmony and self-restraint with the principal motivation being nonviolence, or freedom from causing harm. It has been variously described as virtue, moral discipline and precept.

On the Basis of Morality is one of Arthur Schopenhauer's major works in ethics, in which he argues that morality stems from compassion. Schopenhauer begins with a criticism of Kant's Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, which Schopenhauer considered to be the clearest explanation of Kant's foundation of ethics.

Kantian ethics refers to a deontological ethical theory developed by German philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that: "It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, that could be considered good without limitation except a good will." The theory was developed in the context of Enlightenment rationalism. It states that an action can only be moral if (i) it is motivated by a sense of duty and (ii) its maxim may be rationally willed a universal, objective law.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to humanism:

Higher consciousness is the consciousness of God or, in the words of Dawn DeVries, "the part of the human mind that is capable of transcending animal instincts". While the concept has ancient roots, it was significantly developed in German idealism, and is a central notion in contemporary popular spirituality, including the New Age movement.

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct. The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concern matters of value, and thus comprise the branch of philosophy called axiology.

The concept of moral rights for animals is believed to date as far back as Ancient India, particularly early Jainist and Hindu history. What follows is mainly the history of animal rights in the Western world. There is a rich history of animal protection in the ancient texts, lives, and stories of Eastern, African, and Indigenous peoples.

Buddhist thought and Western philosophy include several parallels.

The relationship between Christianity and animal rights is complex, with different Christian communities coming to different conclusions about the status of animals. The topic is closely related to, but broader than, the practices of Christian vegetarians and the various Christian environmentalist movements.

The respect for animal rights in Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism derives from the doctrine of ahimsa.