Charles Messier was a French astronomer. He published an astronomical catalogue consisting of 110 nebulae and star clusters, which came to be known as the Messier objects, referred to with the letter M and their number between 1 and 110. Messier's purpose for the catalogue was to help astronomical observers distinguish between permanent and transient visually diffuse objects in the sky.

Comet Ikeya–Seki, formally designated C/1965 S1, 1965 VIII, and 1965f, was a long-period comet discovered independently by Kaoru Ikeya and Tsutomu Seki. First observed as a faint telescopic object on September 18, 1965, the first calculations of its orbit suggested that on October 21, it would pass just 450,000 km (280,000 mi) above the Sun's surface, and would probably become extremely bright.

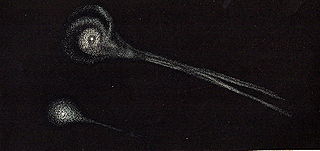

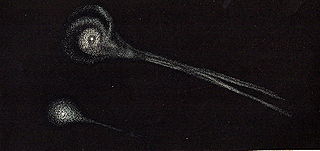

Biela's Comet or Comet Biela was a periodic Jupiter-family comet first recorded in 1772 by Montaigne and Messier and finally identified as periodic in 1826 by Wilhelm von Biela. It was subsequently observed to split in two and has not been seen since 1852. As a result, it is currently considered to have been destroyed, although remnants have survived for some time as a meteor shower, the Andromedids which may show increased activity in 2023.

A sungrazing comet is a comet that passes extremely close to the Sun at perihelion – sometimes within a few thousand kilometres of the Sun's surface. Although small sungrazers can completely evaporate during such a close approach to the Sun, larger sungrazers can survive many perihelion passages. However, the strong evaporation and tidal forces they experience often lead to their fragmentation.

The Kreutz sungrazers are a family of sungrazing comets, characterized by orbits taking them extremely close to the Sun at perihelion. For example, the Great Southern Comet of 1887 passed about 27000 km from the surface of the Sun. They are believed to be fragments of one large comet that broke up several centuries ago and are named for German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz, who first demonstrated that they were related. A Kreutz sungrazer's aphelion is about 170 AU (25 billion km) from the Sun; these sungrazers make their way from the distant outer Solar System from a patch in the sky in Canis Major, to the inner Solar System, to their perihelion point near the Sun, and then leave the inner Solar System in their return trip to their aphelion.

Comet Pereyra was a bright comet which appeared in 1963. It was a member of the Kreutz Sungrazers, a group of comets which pass extremely close to the Sun.

The Great Comet of 1861, formally designated C/1861 J1 and 1861 II, is a long-period comet that was visible to the naked eye for approximately 3 months. It was categorized as a great comet—one of the eight greatest comets of the 19th century.

Comet Ikeya–Zhang is a comet discovered independently by two astronomers from Japan and China in 2002. It has by far the longest orbital period of the numbered periodic comets. It was last observed in October 2002 when it was about 3.3 AU (490 million km) from the Sun.

The Comet of 1729, also known as C/1729 P1 or Comet Sarabat, was an assumed parabolic comet with an absolute magnitude of −3, the brightest ever observed for a comet; it is therefore considered to be potentially the largest comet ever seen. With an assumed eccentricity of 1, it is unknown if this comet will return in a hundred thousand years or be ejected from the Solar System.

Comet McNaught, also known as the Great Comet of 2007 and given the designation C/2006 P1, is a non-periodic comet discovered on 7 August 2006 by British-Australian astronomer Robert H. McNaught using the Uppsala Southern Schmidt Telescope. It was the brightest comet in over 40 years, and was easily visible to the naked eye for observers in the Southern Hemisphere in January and February 2007.

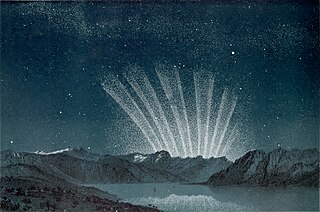

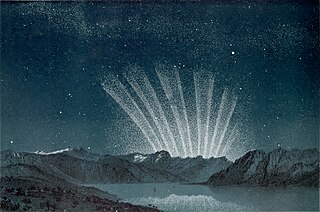

The Great Comet of 1744, whose official designation is C/1743 X1, and which is also known as Comet de Chéseaux or Comet Klinkenberg-Chéseaux, was a spectacular comet that was observed during 1743 and 1744. It was discovered independently in late November 1743 by Jan de Munck, in the second week of December by Dirk Klinkenberg, and, four days later, by Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux. It became visible with the naked eye for several months in 1744 and displayed dramatic and unusual effects in the sky. Its absolute magnitude – or intrinsic brightness – of 0.5 was the sixth highest in recorded history. Its apparent magnitude may have reached as high as −7, leading it to be classified as a Great Comet. This comet is noted especially for developing a 'fan' of six tails after reaching its perihelion.

The Great Comet of 1264 was one of the brightest comets on record. It appeared in July 1264 and remained visible to the end of September. It was first seen during the evenings after sunset, but appeared in its greatest splendor in weeks afterward, when it became visible during the mornings in the northeastern sky, with the tail perceived long before the comet itself rose above the horizon. The head of the comet seemed like an obscure and ill-defined star, and the tail passed from this portion of it like expanded flames, stretching forth towards the mid-heavens to a distance of one hundred degrees from the nucleus. The comet of 1264 was described to have been an object of great size and brilliancy. The comet's splendor was greatest at the end of August and the beginning of September. At that time, when the head was just visible above the eastern horizon in the morning sky, the tail stretched out past the mid-heaven towards the west, or was nearly 100° in length.

The Great Comet of 1901, sometimes known as Comet Viscara, formally designated C/1901 G1, was a comet which became bright in the spring of 1901. Visible exclusively from the southern hemisphere, it was discovered on the morning of April 12, 1901 as a naked-eye object of second magnitude with a short tail. On the day of perihelion passage, the comet's head was reported as deep yellowish in color, trailing a 10-degree tail. It was last seen by the naked eye on May 23.

Comet Lovejoy, formally designated C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy), is a long-period comet and Kreutz sungrazer. It was discovered in November 2011 by Australian amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy. The comet's perihelion took it through the Sun's corona on 16 December 2011, after which it emerged intact, though greatly impacted by the event.

C/1807 R1, also known as the Great Comet of 1807, is a long-period comet. It was visible to naked-eye observers in the northern hemisphere from early September 1807 to late December, and is ranked among the great comets due to its exceptional brightness.

C/1865 B1 was a non-periodic comet, which in 1865 was so bright that it was visible to unaided-eye observations in the Southern Hemisphere. The comet could not be seen from the Northern Hemisphere.

C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) was a comet with a near-parabolic orbit discovered by the ATLAS survey on December 28, 2019. Early predictions based on the brightening rate suggested that the comet could become as bright as magnitude 0 matching the brightness of Vega. It received widespread media coverage due to its dramatic increase in brightness and orbit similar to the Great Comet of 1844, but on March 22, 2020, the comet started disintegrating. Such fragmentation events are very common for Kreutz Sungrazers. The comet continues to fade and did not reach naked eye visibility. By mid-May, comet ATLAS appeared very diffuse even in a telescope. C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS) has not been seen since May 21, 2020.

C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) or Comet NEOWISE is a long period comet with a near-parabolic orbit discovered on March 27, 2020, by astronomers during the NEOWISE mission of the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space telescope. At that time, it was an 18th-magnitude object, located 2 AU away from the Sun and 1.7 AU away from Earth.

C/2021 A1 (Leonard) was a long period comet that was discovered by G. J. Leonard at the Mount Lemmon Observatory on 3 January 2021 when the comet was 5 AU (750 million km) from the Sun. It had a retrograde orbit. The nucleus was about 1 km (0.6 mi) across. It came within 4 million km (2.5 million mi) of Venus, the closest-known cometary approach to Venus.

Comet Kohoutek is a comet that passed close to the Sun towards the end of 1973. Early predictions of the comet's peak brightness suggested that it had the potential to become one of the brightest comets of the 20th century, capturing the attention of the wider public and the press and earning the comet the moniker of "Comet of the Century". Although Kohoutek became rather bright, the comet was ultimately far dimmer than the optimistic projections: its apparent magnitude peaked at only –3 and it was visible for only a short period, quickly dimming below naked-eye visibility by the end of January 1974.