A repertory theatre, also called repertory, rep, true rep or stock, which are also called producing theatres, is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

In American theater, summer stock theater is a theater that presents stage productions only in the summer. The name combines the season with the tradition of staging shows by a resident company, reusing stock scenery and costumes. Summer stock theaters frequently take advantage of seasonal weather by having their productions outdoors, under tents set up temporarily for their use, or in barns.

Ben Iden Payne, also known as B. Iden Payne, was an English actor, director and teacher. Active in professional theater for seventy years, he helped the first modern Repertory Theatre in the United Kingdom, was an early and effective advocate for Elizabethan staging of Shakespeare plays, and served as an inspiration for Shakespeare Companies and University theater programs throughout North America and the British Isles. His name lives on as the name of a theater at the University of Texas as well as annual theater awards presented in Austin, Texas.

Theater in the United States is part of the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the British theater. The central hub of the American theater scene is Manhattan, with its divisions of Broadway, Off-Broadway, and Off-Off-Broadway. Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York, many cities have professional regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons, with some works being produced regionally with hopes of eventually moving to New York. U.S. theater also has an active community theater culture, which relies mainly on local volunteers who may not be actively pursuing a theatrical career.

Peter Frechette is an American actor. He is a stage actor with two Tony Award nominations for Eastern Standard and Our Country's Good, and frequently stars in the plays of Richard Greenberg. He is well known on TV for playing hacker George on the NBC series Profiler and Peter Montefiore on Thirtysomething. In film, he is known for playing T-Bird Louis DiMucci in the musical Grease 2.

Starting in 1896, the Theatrical Syndicate was an organization in the United States that controlled the majority of bookings in the country's leading theatrical attractions. The six-man group was in charge of theatres and bookings. The Syndicate's power would peak in 1907.

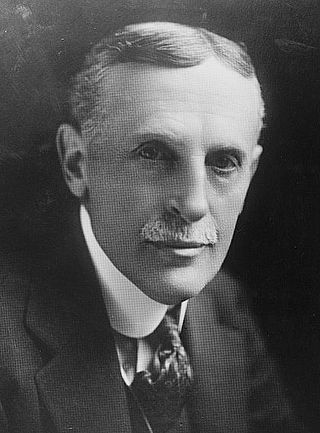

Marc Klaw, was an American lawyer, theatrical producer, theater owner, and a leading figure of the Theatrical Syndicate.

Eva Le Gallienne was a British-born American stage actress, producer, director, translator, and author. A Broadway star by age 21, in 1926 she left Broadway behind to found the Civic Repertory Theatre, where she served as director, producer, and lead actress. Noted for her boldness and idealism, she was a pioneering figure in the American theater, setting the stage for the Off-Broadway and regional theater movements that swept the country later in the 20th century.

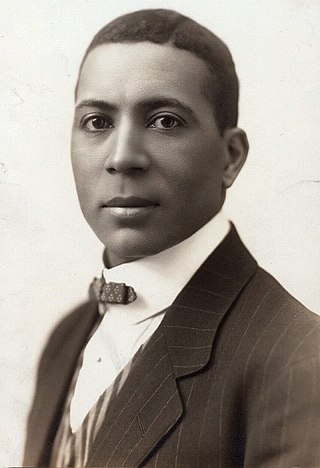

Sherman Houston Dudley was an African-American vaudeville performer and theatre entrepreneur. He gained notability in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century as an individual performer, a composer of ragtime songs, and as a member and later owner of various minstrel shows including the Smart Set Company. Dudley is also notable as one of the first African Americans to combine business with theater, by starting a black theater circuit, in which theaters were owned or operated by African Americans and provided entertainment by and for African Americans. He created the first black operated vaudeville circuit and led the way for what became the Theatre Owners Booking Association (T.O.B.A.).

George Jolly, or Joliffe was an actor, an early actor-manager and a theatre impresario of the middle seventeenth century. He was "an experienced, courageous, and obstinate actor-manager" who proved a persistent rival for the main theatrical figures of Restoration theatre, Sir William Davenant and Thomas Killigrew.

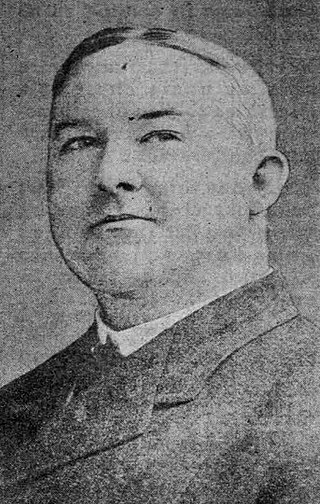

John Cort was an American impresario; his Cort Circuit was one of the first national theater circuits. Along with John Considine and Alexander Pantages, Cort was one of the Seattle-based entrepreneurs who parlayed their success in the years following the Klondike Gold Rush into an impact on America's national theater scene. While Considine and Pantages focused mainly on vaudeville, Cort focused on legitimate theater. At one time, he owned more legitimate theaters than anyone else in the United States, and he eventually became part of the New York theatrical establishment. His Cort Theatre remains a fixture of Broadway.

The American National Theatre and Academy (ANTA) is a non-profit theatre producer and training organization that was established in 1935 to be the official United States national theatre that would be an alternative to the for-profit Broadway houses of the day.

An actor-manager is a leading actor who sets up their own permanent theatrical company and manages the business, sometimes taking over a theatre to perform select plays in which they usually star. It is a method of theatrical production used consistently since the 16th century, particularly common in 19th-century Britain and the United States.

Jules Irving was an American actor, director, educator, and producer, who in the 1950s co-founded the San Francisco Actor's Workshop. When the Actor's Workshop closed in 1966, Irving moved to New York City and became the first Producing Director of the Repertory Company of the Vivian Beaumont Theater of Lincoln Center.

The Orpheum Circuit was a chain of vaudeville and movie theaters. It was founded in 1886, and operated through 1927 when it was merged into the Keith-Albee-Orpheum corporation, ultimately becoming part of the Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO) corporation.

The 1919 Actors' Equity Association strike officially spanned from August 7, 1919, to September 6, 1919. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the theatre industry was revolutionized by powerful management groups that monopolized and centralized the industry. These groups created harsh working conditions for the actors. On May 26, 1913, actors decided to unionize, and they formed the Actors' Equity Association. After many failed attempts to negotiate with the producers and managers for fair treatment and a standard contract, Equity declared a strike against the Producing Managers' Association on August 7, 1919. During the strike, the actors walked out of theaters, held parades in the streets, and performed benefit shows. Equity received support from the theatrical community, the public, and the American Federation of Labor, and on September 6, 1919, the actors won the strike. The producers signed a contract with the AEA that contained nearly all of Equity's demands. The strike was important because it expanded the definition of labor and altered perceptions about what types of careers could organize. The strike also encouraged other groups within the theatre industry to organize.

Samuel F. Nixon, born Samuel Frederic Nirdlinger was an American theater owner. He was known as one of the organizers of the Theatrical Syndicate, which monopolized theatrical bookings in the United States for several years.

L. Lawrence Weber was an American sports promoter, stage show producer and theater manager. He was active in arranging vaudeville shows, legitimate theater and films. He once tried to bypass laws against importing a boxing film to the US by projecting it on a screen just across the border in Canada and filming the screening from the USA side.

The Vaudeville Managers Association (VMA) was a cartel of managers of American vaudeville theaters established in 1900, dominated by the Boston-based Keith-Albee chain. Soon afterwards the Western Vaudeville Managers Association (WVMA) was formed as a cartel of theater owners in Chicago and the west, dominated by the Orpheum Circuit. Although rivals, the two organizations collaborated in booking acts and dealing with the performers' union, the White Rats. By 1913 Edward Franklin Albee II had effective control over both the VMA and WVMA. In the 1920s vaudeville went into decline, unable to compete with film. In 1927 the Keith-Albee and Orpheum chains merged. The next year they became part of RKO Pictures.

Klaw and Erlanger was an entertainment management and production partnership of Marc Klaw and Abraham Lincoln Erlanger based in New York City from 1888 through 1919. While running their own considerable and multi-faceted theatrical businesses on Broadway, they were key figures in the Theatrical Syndicate, the lucrative booking monopoly for first-class legitimate theaters nationwide.