The Vulgate, sometimes referred to as the Latin Vulgate, is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

Textus Receptus refers to the succession of printed editions of the Greek New Testament from Erasmus's Novum Instrumentum omne (1516) to the 1633 Elzevir edition.

The Bible has been translated into many languages from the biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. As of September 2023 all of the Bible has been translated into 736 languages, the New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,658 languages, and smaller portions of the Bible have been translated into 1,264 other languages according to Wycliffe Global Alliance. Thus, at least some portions of the Bible have been translated into 3,658 languages.

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Vetus Latina, also known as Vetus Itala, Itala ("Italian") and Old Italic, and denoted by the siglum , is the collective name given to the Latin translations of biblical texts that preceded the Vulgate.

Hugh of Saint-Cher, O.P. was a French Dominican friar who became a cardinal and noted biblical commentator.

Codex Claromontanus, symbolized by Dp, D2 or 06 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), δ 1026 (von Soden), is a Greek-Latin diglot uncial manuscript of the New Testament, written in an uncial hand on vellum. The Greek and Latin texts are on facing pages, thus it is a "diglot" manuscript, like Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis. The Latin text is designated by d (traditional system) or by 75 in Beuron system.

A corrector is a person or object practicing correction, usually by removing or rectifying errors.

The Bible Historiale was the predominant medieval translation of the Bible into French. It translates from the Latin Vulgate significant portions from the Bible accompanied by selections from the Historia Scholastica by Peter Comestor, a literal-historical commentary that summarizes and interprets episodes from the historical books of the Bible and situates them chronologically with respect to events from pagan history and mythology.

In Biblical studies, a gloss or glossa is an annotation written on margins or within the text of biblical manuscripts or printed editions of the scriptures. With regard to the Hebrew texts, the glosses chiefly contained explanations of purely verbal difficulties of the text; some of these glosses are of importance for the correct reading or understanding of the original Hebrew, while nearly all have contributed to its uniform transmission since the 11th century. Later on, Christian glosses also contained scriptural commentaries; St. Jerome extensively used glosses in the process of translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible.

Novum Instrumentum Omne, later called Novum Testamentum Omne, was a bilingual Latin-Greek New Testament with scholarly annotations, and the first printed New Testament of the Greek to be published. It was prepared by Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) and printed by Johann Froben (1460–1527) of Basel.

Bible translations in the Middle Ages discussions are rare in contrast to Late Antiquity, when the Bibles available to most Christians were in the local vernacular. In a process seen in many other religions, as languages changed, and in Western Europe languages with no tradition of being written down became dominant, the prevailing vernacular translations remained in place, despite gradually becoming sacred languages, incomprehensible to the majority of the population in many places. In Western Europe, the Latin Vulgate, itself originally a translation into the vernacular, was the standard text of the Bible, and full or partial translations into a vernacular language were uncommon until the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period.

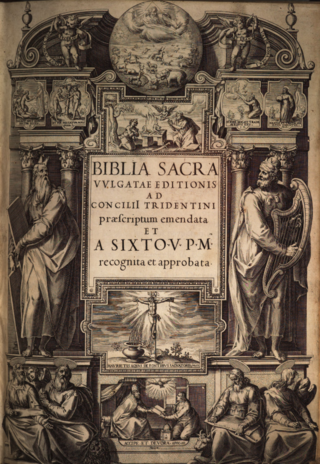

The Sixtine Vulgate or Sistine Vulgate is the edition of the Vulgate—a 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible that was written largely by Jerome—which was published in 1590, prepared by a commission on the orders of Pope Sixtus V and edited by himself. It was the first edition of the Vulgate authorised by a pope. Its official recognition was short-lived; the edition was replaced in 1592 by the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.

The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate or Clementine Vulgate is the edition promulgated in 1592 by Pope Clement VIII of the Vulgate—a 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible that was written largely by Jerome. It was the second edition of the Vulgate to be authorised by the Catholic Church, the first being the Sixtine Vulgate. The Sixto-Clementine Vulgate was used officially in the Catholic Church until 1979, when the Nova Vulgata was promulgated by Pope John Paul II.

The Codex Theodulphianus, designated Θ, is a 10th-century Latin manuscript of the Old and New Testament. The text, written on vellum, is a version of the Latin Vulgate Bible. It contains the whole Bible, with some parts written on purple vellum.

William of Luxi, O.P., also Guillelmus de Luxi or, was born in the region of Burgundy, France, sometime during the first quarter of the thirteenth century. He was a Dominican friar who became regent master of Theology at the University of Paris and a noted biblical exegete and preacher.

The Paris Bible was a standardized format of codex of the Vulgate Latin Bible originally produced in Paris in the 13th century. These bibles signalled a significant change in the organization and structure of medieval bibles and were the template upon which the structure of the modern bible is based.

The Abbey Bible is a complex illuminated manuscript, created in Bologna, Italy in the mid-thirteenth century. It is an example of a Gothic-style Bible, with significant Byzantine influence. This manuscript is especially known for its distinctive marginal imagery. The Abbey Bible now resides at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, CA.

The Vulgate is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible, largely edited by Jerome, which functioned as the Catholic Church's de facto standard version during the Middle Ages. The original Vulgate produced by Jerome around 382 has been lost, but texts of the Vulgate have been preserved in numerous manuscripts, albeit with many textual variants.

The Zirc Bestiary is a 15th-century Hungarian illuminated manuscript copy of a medieval bestiary, a book describing the appearance and habits of a number of familiar and exotic animals, both real and legendary. The animals' characteristics are frequently allegorized, with the addition of a Christian moral. The Latin-language work was kept in the Cistercian Zirc Abbey, now it belongs to the property of the National Széchényi Library (OSZK).