The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was a historical period of Germany from 9 November 1918 to 23 March 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclaimed itself, as the German Republic. The period's informal name is derived from the city of Weimar, which hosted the constituent assembly that established its government. In English, the republic was usually simply called "Germany", with "Weimar Republic" not commonly used until the 1930s.

Friedrich Ebert was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

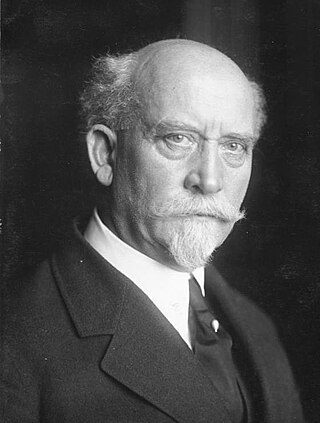

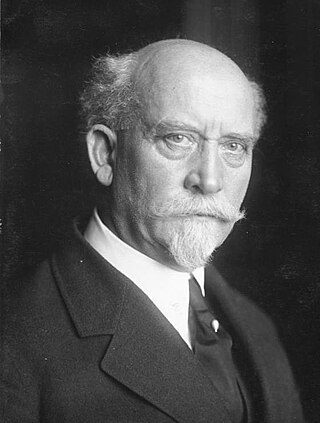

Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In the first quarter of the 20th century he played a leading role in both his party and in the young Weimar Republic. During the German Revolution of 1918–1919 that broke out after Germany's defeat in World War I, Scheidemann proclaimed a German Republic from a balcony of the Reichstag building. In 1919 he was elected Reich Minister President by the National Assembly meeting in Weimar to write a constitution for the republic. He resigned the office the same year due to a lack of unanimity in the cabinet on whether or not to accept the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

The German Revolution of 1918–1919, also known as the November Revolution, was an uprising started by workers and soldiers in the final days of World War I. It quickly and almost bloodlessly brought down the German Empire, then in its more violent second stage, the supporters of a parliamentary republic were victorious over those who wanted a soviet-style council republic. The defeat of the forces of the far left cleared the way for the establishment of the Weimar Republic.

Gustav Noske was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He served as the first Minister of Defence (Reichswehrminister) of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920. Noske was known for using army and paramilitary forces to suppress the socialist/communist uprisings of 1919.

Hugo Haase was a German socialist politician, jurist and pacifist. With Friedrich Ebert, he co-chaired of the Council of the People's Deputies during the German Revolution of 1918–19.

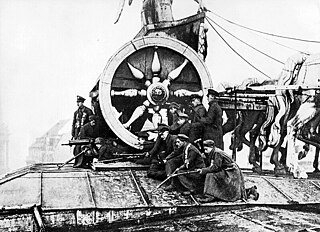

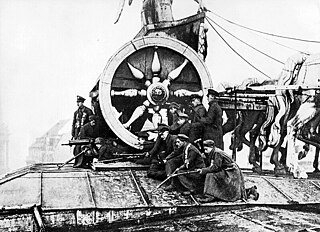

The 1918 Christmas crisis was a brief battle between the socialist revolutionary Volksmarinedivision and regular German army units on 24 December 1918 during the German Revolution of 1918–19. It took place at the Berlin Palace, the main residence of the House of Hohenzollern.

The Ebert–Groener pact, sometimes called the Ebert-Groener deal, was an agreement between the Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert, at the time the Chancellor of Germany, and Wilhelm Groener, Quartermaster General of the German Army, on November 10, 1918. This occurred on the day after the German Revolution had brought Ebert to power.

The Weimar National Assembly, officially the German National Constitutional Assembly, was the popularly elected constitutional convention and de facto parliament of Germany from 6 February 1919 to 21 May 1920. As part of its duties as the interim government, it debated and reluctantly approved the Treaty of Versailles that codified the peace terms between Germany and the victorious Allies of World War I. The Assembly drew up and approved the Weimar Constitution that was in force from 1919 to 1933. With its work completed, the National Assembly was dissolved on 21 May 1920. Following the election of 6 June 1920, the new Reichstag met for the first time on 24 June 1920, taking the place of the Assembly.

Emil Barth was a German Social Democratic party worker and socialist politician who became a key figure in the German Revolution of 1918.

During the First World War (1914–1918), the Revolutionary Stewards were shop stewards who were independent from the official unions and freely chosen by workers in various German industries. They rejected the war policies of the German Empire and the support which parliamentary representatives of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) gave to the policies. They also played a role during the German Revolution of 1918–19.

The Scheidemann cabinet, headed by Minister President Philipp Scheidemann of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), was Germany's first democratically elected national government. It took office on 13 February 1919, three months after the collapse of the German Empire following Germany's defeat in World War I. Although the Weimar Constitution was not in force yet, it is generally counted as the first government of the Weimar Republic.

The Spartacist uprising, also known as the January uprising, was an armed uprising that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolution that broke out following Germany's defeat in World War I. The uprising was primarily a power struggle between the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) led by Friedrich Ebert, which favored a social democracy, and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, which wanted to set up a council republic similar to the one established by the Bolsheviks in Russia. In 1914 Liebknecht and Luxemburg had founded the Marxist Spartacus League, which gave the uprising its popular name.

The Spartacus League was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the International Group by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and other members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) who were dissatisfied with the party's official policies in support of the war. In 1916 it renamed itself the Spartacus Group and in 1917 joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), which had split off from the SPD as its left wing faction.

The Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany was the name officially used by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) between April 1917 and September 1922. The name differentiated it from the Independent Social Democratic Party, which split from the SPD as a result of the party majority's support of the government during the First World War.

The Volksmarinedivision was an armed unit formed on 11 November 1918 during the November Revolution that broke out in Germany following its defeat in World War I. At its peak late that month, the People's Navy Division had about 3,200 members. In the struggles between the various elements involved in the revolution to determine Germany's future form of government, it initially supported the moderate socialist interim government of Friedrich Ebert and the Council of the People's Deputies. By December of 1918 it had turned more to the left and was involved in skirmishes against government troops. In March 1919, after the success of the Ebert government in the elections to the National Assembly that drew up the Weimar Constitution, the People's Navy Division was disbanded and 30 of its members were summarily shot by members of a Freikorps unit.

The proclamation of the republic in Germany took place in Berlin twice on 9 November 1918, the first at the Reichstag building by Philipp Scheidemann of the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) and the second a few hours later by Karl Liebknecht, the leader of the Marxist Spartacus League, at the Berlin Palace.

The German constitutional reforms of October 1918 consisted of several constitutional and legislative changes that transformed the German Empire into a parliamentary monarchy for a brief period at the end of the First World War. The reforms, which took effect on 28 October 1918, made the office of Reich chancellor dependent on the confidence of the Reichstag rather than that of the German emperor and required the consent of both the Reichstag and the Bundesrat for declarations of war and for peace agreements.

The Prussian Revolutionary Cabinet was the provisional state government of Prussia from November 14, 1918 to March 25, 1919. It was based on a coalition of Majority Social Democrats (MSPD) and Independent Social Democrats (USPD), as was the Council of the People's Deputies, which was formed at the Reich level. The Prussian cabinet was revolutionary because it was not formed on the basis of the previous Prussian constitution of 1848/1850.

The German workers' and soldiers' councils of 1918–1919 were short-lived revolutionary bodies that spread the German Revolution to cities across the German Empire during the final days of World War I. Meeting little to no resistance, they formed quickly, took over city governments and key buildings, caused most of the locally stationed military to flee and brought about the abdications all of Germany's ruling monarchs, including Emperor Wilhelm II, when they reached Berlin on 9 November 1918.