Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych, given the epithet "the Great", was Prince of Novgorod from 970 and Grand Prince of Kiev from 978 until his death in 1015. The Eastern Orthodox Church canonised him as Saint Vladimir.

The Mongol Empire invaded and conquered much of Kievan Rus' in the mid-13th century, sacking numerous cities including the largest such as Kiev and Chernigov. The Mongol siege and sack of Kiev in 1240 is generally held to mark the end of Kievan Rus' as a distinct, singular polity. Many other Rus' principalities and urban centres in the northwest and southwest escaped destruction or suffered little to no damage from the Mongol invasion, including Galicia-Volhynia, Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, Polotsk, Vitebsk, and probably Rostov and Uglich.

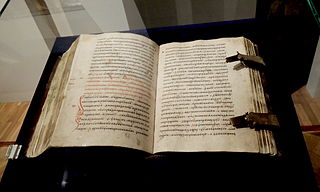

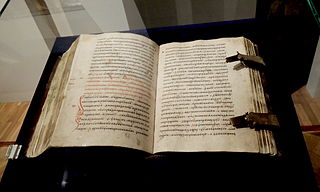

The Russian Primary Chronicle, commonly shortened to Primary Chronicle, is a chronicle of Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110. It is believed to have been originally compiled in or near Kiev in the 1110s. Tradition ascribed its compilation to the monk Nestor beginning in the 17th century, but this is no longer believed to have been the case.

The Grand Prince of Kiev was the title of the monarch of Kievan Rus', residing in Kiev from the 10th to 13th centuries. In the 13th century, Kiev became an appanage principality first of the grand prince of Vladimir and the Mongol Golden Horde governors, and later was taken over by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

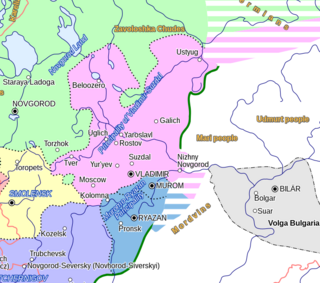

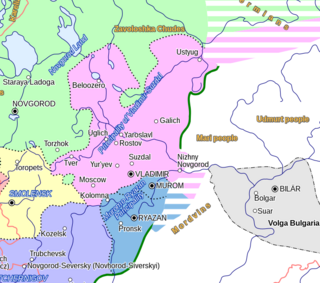

Vladimir-Suzdal, formally known as the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal or Grand Principality of Vladimir (1157–1331), also as Vladimir-Suzdalian Rus', was one of the major principalities that succeeded Kievan Rus' in the late 12th century, centered in Vladimir-on-Klyazma. With time the principality grew into a grand principality divided into several smaller principalities. After being conquered by the Mongol Empire, the principality became a self-governed state headed by its own nobility. A governorship of principality, however, was prescribed by a jarlig issued from the Golden Horde to a Rurikid sovereign.

Old East Slavic was a language used by the East Slavs from the 7th or 8th century to the 13th or 14th century, until it diverged into the Russian and Ruthenian languages. Ruthenian eventually evolved into the Belarusian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian languages.

Cyril of Turov, alternately Kirill of Turov was a bishop and saint of the Russian Orthodox Church. He was one of the first and finest theologians of Kievan Rus'; he lived in Principality of Turov, now southern Belarus. His feast day in the Eastern Orthodox Church is on 28 April.

The Christianization of Kievan Rus' was a long and complicated process that took place in several stages. In 867, Patriarch Photius of Constantinople told other Christian patriarchs that the Rus' people were converting enthusiastically, but his efforts seem to have entailed no lasting consequences, since the Russian Primary Chronicle and other Slavonic sources describe the tenth-century Rus' as still firmly entrenched in Slavic paganism. The traditional view, as recorded in the Russian Primary Chronicle, is that the definitive Christianization of Kievan Rus' dates happened c. 988, when Vladimir the Great was baptized in Chersonesus (Korsun) and proceeded to baptize his family and people in Kiev. The latter events are traditionally referred to as baptism of Rus' in Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian literature.

Old East Slavic literature, also known as Old Russian literature, is a collection of literary works of Rus' authors, which includes all the works of ancient Rus' theologians, historians, philosophers, translators, etc., and written in Old East Slavic. It is a general term that unites the common literary heritage of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine of the ancient period. In terms of genre construction, it has a number of differences from medieval European literature. The greatest influence on the literature of ancient Rus' was exerted by old Polish and old Serbian literature.

The Volhynians were an East Slavic tribe of the Early Middle Ages and the Principality of Volhynia in 987–1199.

The architecture of Kievan Rus' comes from the medieval state of Kievan Rus' which incorporated parts of what is now modern Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus, and was centered on Kiev and Novgorod. Its architecture is the earliest period of Russian and Ukrainian architecture, using the foundations of Byzantine culture but with great use of innovations and architectural features. Most remains are Russian Orthodox churches or parts of the gates and fortifications of cities.

The Principality of Polotsk, also known as the Duchy of Polotsk or Polotskian Rus', was a medieval principality of the Early East Slavs. The origin and date of state establishment is uncertain. Chronicles of Kievan Rus' mention Polotsk being conquered by Vladimir the Great, and thereafter it became associated with Kievan Rus' and its ruling Rurik dynasty.

Rusʹ Khaganate, or kaganate of Rus is a name applied by some modern historians to a hypothetical polity suggested to have existed during a poorly documented period in the history of Eastern Europe between c. 830 and the 890s.

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus' was a state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century. The name was coined by Russian historians in the 19th century. Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse, and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rus' as their cultural ancestor, with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it, and the name Kievan Rus' derived from what is now the capital of Ukraine. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rus' stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east, uniting the East Slavic tribes.

The Sermon on Law and Grace is a sermon written by the Kievan Metropolitan Hilarion. It is one of the earliest Slavonic texts available, having been written several decades before the Primary Chronicle. Since Hilarion was considered to be a writer worthy of imitation, this sermon was very influential in the further development of both the style and content of Kievan Rus' literature.

The siege of Kiev by the Mongols took place between 28 November and 6 December 1240, and resulted in a Mongol victory. It was a heavy morale and military blow to the Principality of Galicia–Volhynia, which was forced to submit to Mongol suzerainty, and allowed Batu Khan to proceed westward into Central Europe.

In the 9th century, Christianity was spreading throughout Europe, being promoted especially in the Carolingian Empire, its eastern neighbours, Scandinavia, and northern Spain. In 800, Charlemagne was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor, which continued the Photian schism.

This is a select bibliography of post-World War II English-language books and journal articles about the Early Slavs and Rus' and its borderlands until the Mongol invasions beginning in 1223. Book entries may have references to reviews published in academic journals or major newspapers when these could be considered helpful.

Topical outline of articles about Slavic history and culture. This outline is an overview of Slavic topics; for outlines related to specific Slavic groups and topics, see the links in the Other Slavic outlines section below.