The gray whale, also known as the grey whale, gray back whale, Pacific gray whale, Korean gray whale, or California gray whale, is a baleen whale that migrates between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of 14.9 meters (49 ft), a weight of up to 41 tonnes (90,000 lb) and lives between 55 and 70 years, although one female was estimated to be 75–80 years of age. The common name of the whale comes from the gray patches and white mottling on its dark skin. Gray whales were once called devil fish because of their fighting behavior when hunted. The gray whale is the sole living species in the genus Eschrichtius. It is the sole living genus in the family Eschrichtiidae, however some recent studies classify it as a member of the family Balaenopteridae. This mammal is descended from filter-feeding whales that appeared during the Neogene.

Porpoises are small cetaceans classified under the family Phocoenidae. Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals and belugas than to the true dolphins. There are eight extant species of porpoise, all among the smallest of the toothed whales. Porpoises are distinguished from dolphins by their flattened, spade-shaped teeth distinct from the conical teeth of dolphins, and lack of a pronounced beak, although some dolphins also lack a pronounced beak. Porpoises, and other cetaceans, belong to the clade Cetartiodactyla with even-toed ungulates.

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine (saltwater) ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine environments for feeding and survival.

The common minke whale or northern minke whale is a species of minke whale within the suborder of baleen whales.

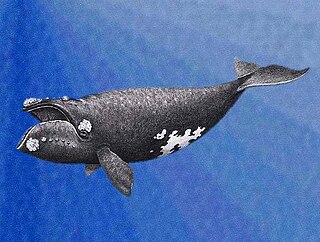

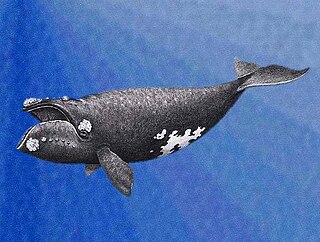

Right whales are three species of large baleen whales of the genus Eubalaena: the North Atlantic right whale, the North Pacific right whale and the Southern right whale. They are classified in the family Balaenidae with the bowhead whale. Right whales have rotund bodies with arching rostrums, V-shaped blowholes and dark gray or black skin. The most distinguishing feature of a right whale is the rough patches of skin on its head, which appear white due to parasitism by whale lice. Right whales are typically 13–17 m (43–56 ft) long and weigh up to 100 short tons or more.

The North Pacific right whale is a very large, thickset baleen whale species that is extremely rare and endangered.

The short-finned pilot whale is one of the two species of cetaceans in the genus Globicephala, which it shares with the long-finned pilot whale. It is part of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae).

The sei whale is a baleen whale. It is one of ten rorqual species, and the third-largest member after the blue and fin whales. They can grow up to 19.5 m (64 ft) in length and weigh as much as 28 t. Two subspecies are recognized: B. b. borealis and B. b. schlegelii. The whale's ventral surface has sporadic markings ranging from light grey to white, and its body is usually dark steel grey in color. It is among the fastest of all cetaceans, and can reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) over short distances.

The four-toothed whales or giant beaked whales are beaked whales in the genus Berardius. They include Arnoux's beaked whale in cold Southern Hemispheric waters, and Baird's beaked whale in the cold temperate waters of the North Pacific. A third species, Sato's beaked whale, was distinguished from B. bairdii in the 2010s.

The melon-headed whale, also known less commonly as the electra dolphin, little killer whale, or many-toothed blackfish, is a toothed whale of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). The common name is derived from the head shape. Melon-headed whales are widely distributed throughout deep tropical and subtropical waters worldwide, but they are rarely encountered at sea. They are found near shore mostly around oceanic islands, such as Hawaii, French Polynesia, and the Philippines.

The northern right whale dolphin is a small, slender species of cetacean found in the cold and temperate waters of the North Pacific Ocean. Lacking a dorsal fin, and appearing superficially porpoise-like, it is one of the two species of right whale dolphin.

The pantropical spotted dolphin is a species of dolphin found in all the world's temperate and tropical oceans. The species was beginning to come under threat due to the killing of millions of individuals in tuna purse seines. In the 1980s, the rise of "dolphin-friendly" tuna capture methods saved millions of the species in the eastern Pacific Ocean and it is now one of the most abundant dolphin species in the world.

The dwarf sperm whale is a sperm whale that inhabits temperate and tropical oceans worldwide, in particular continental shelves and slopes. It was first described by biologist Richard Owen in 1866, based on illustrations by naturalist Sir Walter Elliot. The species was considered to be synonymous with the pygmy sperm whale from 1878 until 1998. The dwarf sperm whale is a small whale, 2 to 2.7 m and 136 to 272 kg, that has a grey coloration, square head, small jaw, and robust body. Its appearance is very similar to the pygmy sperm whale, distinguished mainly by the position of the dorsal fin on the body–nearer the middle in the dwarf sperm whale and nearer the tail in the other.

Cetacean bycatch is the accidental capture of non-target cetacean species such as dolphins, porpoises, and whales by fisheries. Bycatch can be caused by entanglement in fishing nets and lines, or direct capture by hooks or in trawl nets.

The bowhead whale is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and is the only living representative of the genus Balaena. It is the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, and is named after its characteristic massive triangular skull, which it uses to break through Arctic ice. Other common names of the species included the Greenland right whale, Arctic whale, steeple-top, and polar whale.

Whale conservation refers to the conservation of whales.

William F. Perrin was an American biologist specializing in the fields of cetacean taxonomy, reproductive biology, and conservation biology. He is best known for his work documenting the unsustainable mortality of hundreds of thousands of dolphins per year in the tuna purse-seine fishery of the eastern tropical Pacific. This work became a primary motivation for the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972). His work on cetacean taxonomy was acknowledged in 2002 when a newly recognized species of beaked whale, Perrin's beaked whale, which was named in his honor.

Dr. Amanda Bradford is a marine mammal biologist who is currently researching cetacean population dynamics for the National Marine Fisheries Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Bradford is currently a Research Ecologist with the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center's Cetacean Research Program. Her research primarily focuses on assessing populations of cetaceans, including evaluating population size, health, and impacts of human-caused threats, such as fisheries interactions. Bradford is a cofounder and organizer of the Women in Marine Mammal Science (WIMMS) Initiative.