Direct action is militant political action outside the usual political channels.

Contents

Direct action may also refer to:

Direct action is militant political action outside the usual political channels.

Direct action may also refer to:

Propaganda of the deed is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

Action Directe is a short 15-metre (49 ft) sport climb at the limestone Waldkopf crag in Frankenjura, Germany. When it was first climbed by German climber Wolfgang Güllich in 1991, it became the first climb in the world to have a consensus 9a (5.14d) grade. Action Directe is considered an important and historic route in rock climbing history, and is one of the most attempted climbs at its grade, where it is considered the "benchmark" for the level of 9a. The plyometric training techniques and customized equipment that Güllich used to prepare for the unique physical demands of Action Directe also revolutionized climbing and what could be achieved.

Action Directe was a French far-left militant group that originated from the anti-Franco struggle and the autonomous movement, and was responsible for violent attacks in France between 1979 and 1987. Members of the group considered themselves libertarian communists who had formed an "urban guerrilla organization". The French government banned the group. During its existence, AD's members murdered 12 people, and wounded a further 26. It associated at various times with the Red Brigades (Italy), Red Army Faction, Prima Linea (Italy), Armed Nuclei for Popular Autonomy (France), Communist Combatant Cells, Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Factions, Irish National Liberation Army, and others.

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of classical anarchism.

Red flag may refer to:

Fernand-Léonce-Émile Pelloutier was a French anarchist and syndicalist.

In the United States, anarchism began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and campaigning for diverse social reforms in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency.

Direct Action Day was the day the All-India Muslim League decided to take "direct action" for a separate Muslim homeland after the British exit from India. Also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, it was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta in the Bengal province of British India. The day also marked the start of what is known as The Week of the Long Knives. While there is a certain degree of consensus on the magnitude of the killings, including their short-term consequences, controversy remains regarding the exact sequence of events, the various actors' responsibility and the long-term political consequences.

Direct Action: Memoirs of an Urban Guerrilla is a memoir by the Canadian anarchist Ann Hansen. It was published in 2001 simultaneously by the anarchist book publisher AK Press in the United States and Between the Lines Books in Canada. An audio CD was released by the left-wing Canadian record label G7 Welcoming Committee Records on October 14, 2003 under the name Direct Action: Reflections on Armed Resistance and the Squamish Five.

Autonomism, also known as Autonomist Marxism, is an anti-capitalist social movement and Marxist-based theoretical current that first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism. Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tendencies became significant after influence from the Situationists, the failure of Italian far-left movements in the 1970s, and the emergence of a number of important theorists including Antonio Negri, who had contributed to the 1969 founding of Potere Operaio as well as Mario Tronti, Paolo Virno and Franco "Bifo" Berardi.

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigades. According to journalist Brian Doherty, "The number of people who subscribed to the anarchist movement's many publications was in the tens of thousands in France alone."

Anarchism was an influential contributor to the social politics of the First Brazilian Republic. During the epoch of mass migrations of European labourers at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, anarchist ideas started to spread, particularly amongst the country’s labour movement. Along with the labour migrants, many Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and German political exiles arrived, many holding anarchist or anarcho-syndicalist ideas. Some did not come as exiles but rather as a type of political entrepreneur, including Giovanni Rossi's anarchist commune, the Cecília Colony, which lasted few years but at one point consisted of 200 individuals.

The Argentine anarchist movement was the strongest such movement in South America. It was strongest between 1890 and the start of a series of military governments in 1930. During this period, it was dominated by anarchist communists and anarcho-syndicalists. The movement's theories were a hybrid of European anarchist thought and local elements, just as it consisted demographically of both European immigrant workers and native Argentines.

Émile Pouget was a French journalist, pamphleteer and trade unionist. His combination of anarchist political theory and revolutionary syndicalist tactics has led several authors to identify Pouget as an early anarcho-syndicalist.

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice or to solve perceived problems.

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based on a political program and periodic congresses. Instead, insurrectionary anarchists advocate informal organization and small affinity group based organization. Insurrectionary anarchists put value in attack, permanent class conflict and a refusal to negotiate or compromise with class enemies.

Anarchism in Norway first emerged in the 1870s. Some of the first to call themselves anarchists in Norway were Arne Garborg and Ivar Mortensson-Egnund. They ran the radical target magazine Fedraheimen which came out 1877–91. Gradually the magazine became more and more anarchist-oriented, and towards the end of its life it had the subtitle Anarchist-Communist Body. The anarchist author Hans Jæger published the book "The Bible of Anarchy" in 1906, and in recent times Jens Bjørneboe has been a spokesman for anarchism – among other things in the book "Police and anarchy".

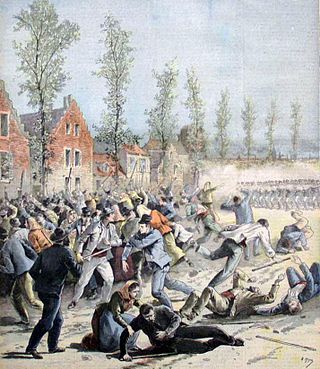

Anarchism spread into Belgium as Communards took refuge in Brussels with the fall of the Paris Commune. Most Belgian members in the First International joined the anarchist Jura Federation after the socialist schism. Belgian anarchists also organized the 1886 Walloon uprising, the Libertarian Communist Group, and several Bruxellois newspapers at the turn of the century. Apart from new publications, the movement dissipated through the internecine antimilitarism in the interwar period. Several groups emerged mid-century for social justice and anti-fascism.

Anarchism in Indonesia has its roots in the anti-colonial struggle against the Dutch Empire. It became an organized movement at the behest of Chinese anarchist immigrants, who played a key part in the development of the workers' movement in the country. The anarchist movement was suppressed, first by the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, then by the successive regimes of Sukarno and Suharto, before finally re-emerging in the 1990s.

Anarchism in El Salvador reached its peak during the labour movement of the 1920s, in which anarcho-syndicalists played a leading role. The movement was subsequently suppressed by the military dictatorship before experiencing a resurgence in the 21st century.