A pandemic is an epidemic of disease that has spread across a large region; for instance multiple continents, or even worldwide. A widespread endemic disease that is stable in terms of how many people are getting sick from it is not a pandemic. Further, flu pandemics generally exclude recurrences of seasonal flu. Throughout history, there have been a number of pandemics, such as smallpox and tuberculosis. One of the most devastating pandemics was the Black Death, which killed over 20 million people in 1350. The most recent pandemics include the HIV pandemic as well as the 1918 and 2009 H1N1 pandemics.

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been exposed to a communicable disease, but do not have a confirmed medical diagnosis. The term is often used synonymously with medical isolation, in which those confirmed to be infected with a communicable disease are isolated from the healthy population.

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains particularly in the back, and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is increased.

Scarlet fever is a disease which can occur as a result of a group A streptococcus infection, also known as Streptococcus pyogenes. The signs and symptoms include a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, and a characteristic rash. The rash is red and feels like sandpaper and the tongue may be red and bumpy. It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age.

Major Walter Reed, M.D., U.S. Army, was a U.S. Army physician who in 1901 led the team that confirmed the theory of the Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species, rather than by direct contact. This insight gave impetus to the new fields of epidemiology and biomedicine, and most immediately allowed the resumption and completion of work on the Panama Canal (1904–1914) by the United States. Reed followed work started by Carlos Finlay and directed by George Miller Sternberg, who has been called the "first U.S. bacteriologist".

One of the greatest challenges facing the builders of the Panama Canal was dealing with the tropical diseases rife in the area. The health measures taken during the construction contributed greatly to the success of the canal's construction. These included general health care, the provision of an extensive health infrastructure, and a major program to eradicate disease-carrying mosquitoes from the area.

Carlos Juan Finlay was a Cuban epidemiologist recognized as a pioneer in the research of yellow fever, determining that it was transmitted through mosquitoes Aedes aegypti.

Cordon sanitaire is a French phrase that, literally translated, means "sanitary cordon". It originally denoted a barrier implemented to stop the spread of infectious diseases. It may be used interchangeably with the term "quarantine", and although the terms are related, cordon sanitaire refers to the restriction of movement of people into or out of a defined geographic area, such as a community. The term is also often used metaphorically, in English, to refer to attempts to prevent the spread of an ideology deemed unwanted or dangerous, such as the containment policy adopted by George F. Kennan against the Soviet Union.

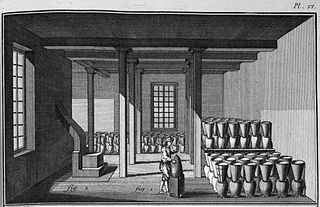

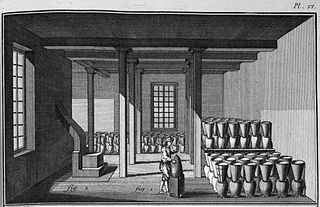

A lazaretto or lazaret is a quarantine station for maritime travellers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings. In some lazarets, postal items were also disinfected, usually by fumigation. This practice was still being done as late as 1936, albeit in rare cases. A leper colony administered by a Christian religious order was often called a lazar house, after the parable of Lazarus the beggar.

Aircraft disinsection is the use of insecticide on international flights and in other closed spaces for insect and disease control. Confusion with disinfection, the elimination of microbes on surfaces, is not uncommon. Insect vectors of disease, mostly mosquitoes, have been introduced into and become indigenous in geographic areas where they were not previously present. Dengue, chikungunya and Zika spread across the Pacific and into the Americas by means of the airline networks. Cases of "airport malaria", in which live malaria-carrying mosquitoes disembark and infect people near the airport, may increase with global warming.

During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, 5,000 or more people were listed in the official register of deaths between August 1 and November 9. The vast majority of them died of yellow fever, making the epidemic in the city of 50,000 people one of the most severe in United States history. By the end of September, 20,000 people had fled the city. The mortality rate peaked in October, before frost finally killed the mosquitoes and brought an end to the epidemic in November. Doctors tried a variety of treatments, but knew neither the origin of the fever nor that it was transmitted by mosquitoes.

Mosquito-borne diseases or mosquito-borne illnesses are diseases caused by bacteria, viruses or parasites transmitted by mosquitoes. They can transmit disease without being affected themselves. Nearly 700 million people get a mosquito-borne illness each year resulting in over one million deaths.

The evolutionary origins of yellow fever most likely lie in Africa. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the virus originated from East or Central Africa, with transmission between primates and humans, and spread from there to West Africa. The virus as well as the vector Aedes aegypti, a mosquito species, were probably brought to the western hemisphere and the Americas by slave trade ships from Africa after the first European exploration in 1492.

Jean Charles Faget was a medical doctor born on June 26, 1818 in New Orleans. He is best known for the Faget sign—a medical sign that is the unusual combination of fever and bradycardia. The sign is an important diagnostic symptom of yellow fever.

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the seventh pandemic originating in Indonesia in 1961. Additionally, there have been many documented cholera outbreaks, such as a 1991-1994 outbreak in South America and, more recently, the 2016–19 Yemen cholera outbreak.

Antoine-Germain Labarraque was a French chemist and pharmacist, notable for formulating and finding important uses for "Eau de Labarraque" or "Labarraque's solution", a solution of sodium hypochlorite widely used as a disinfectant and deodoriser.

John Laing Leal was a physician and water treatment expert who, in 1908, was responsible for conceiving and implementing the first disinfection of a U.S. drinking water supply using chlorine. He was one of the principal expert witnesses at two trials which examined the quality of the water supply in Jersey City, New Jersey, and which evaluated the safety and utility of chlorine for production of "pure and wholesome" drinking water. The second trial verdict approved the use of chlorine to disinfect drinking water which led to an explosion of its use in water supplies across the U.S.

Water chlorination is the process of adding chlorine or chlorine compounds such as sodium hypochlorite to water. This method is used to kill certain bacteria and other microbes in tap water as chlorine is highly toxic. In particular, chlorination is used to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid.

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century reached epidemic proportions in the case of one emerging infectious disease: cholera. Other important diseases at that time in Europe and other regions included smallpox, typhus and yellow fever.

On 20 January 2016, the health minister of Angola reported 23 cases of yellow fever with 7 deaths among Eritrean and Congolese citizens living in Angola in Viana municipality, a suburb of the capital of Luanda. The first cases were reported in Eritrean visitors beginning on 5 December 2015 and confirmed by the Pasteur WHO reference laboratory in Dakar, Senegal in January. The outbreak was classified as an urban cycle of yellow fever transmission, which can spread rapidly. A preliminary finding that the strain of the yellow fever virus was closely related to a strain identified in a 1971 outbreak in Angola was confirmed in August 2016. Moderators from ProMED-mail stressed the importance of initiating a vaccination campaign immediately to prevent further spread. The CDC classified the outbreak as Watch Level 2 on 7 April 2016. The WHO declared it a grade 2 event on its emergency response framework having moderate public health consequences.