In physics, a dipole is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs in two ways:

An intermolecular force (IMF) is the force that mediates interaction between molecules, including the electromagnetic forces of attraction or repulsion which act between atoms and other types of neighbouring particles, e.g. atoms or ions. Intermolecular forces are weak relative to intramolecular forces – the forces which hold a molecule together. For example, the covalent bond, involving sharing electron pairs between atoms, is much stronger than the forces present between neighboring molecules. Both sets of forces are essential parts of force fields frequently used in molecular mechanics.

In chemistry, polarity is a separation of electric charge leading to a molecule or its chemical groups having an electric dipole moment, with a negatively charged end and a positively charged end.

Accelerator physics is a branch of applied physics, concerned with designing, building and operating particle accelerators. As such, it can be described as the study of motion, manipulation and observation of relativistic charged particle beams and their interaction with accelerator structures by electromagnetic fields.

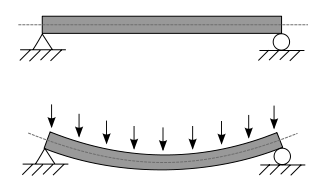

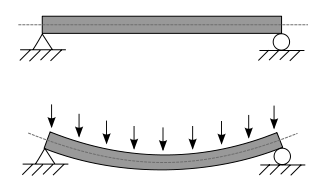

A beam is a structural element that primarily resists loads applied laterally to the beam's axis. Its mode of deflection is primarily by bending. The loads applied to the beam result in reaction forces at the beam's support points. The total effect of all the forces acting on the beam is to produce shear forces and bending moments within the beams, that in turn induce internal stresses, strains and deflections of the beam. Beams are characterized by their manner of support, profile, equilibrium conditions, length, and their material.

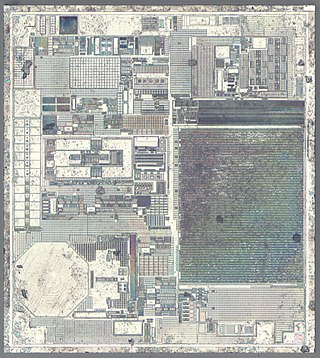

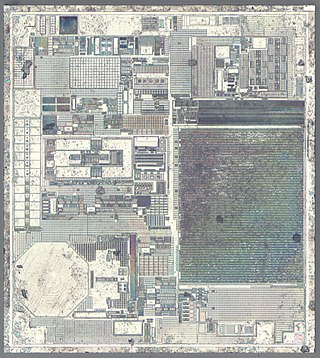

Nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) are a class of devices integrating electrical and mechanical functionality on the nanoscale. NEMS form the next logical miniaturization step from so-called microelectromechanical systems, or MEMS devices. NEMS typically integrate transistor-like nanoelectronics with mechanical actuators, pumps, or motors, and may thereby form physical, biological, and chemical sensors. The name derives from typical device dimensions in the nanometer range, leading to low mass, high mechanical resonance frequencies, potentially large quantum mechanical effects such as zero point motion, and a high surface-to-volume ratio useful for surface-based sensing mechanisms. Applications include accelerometers and sensors to detect chemical substances in the air.

Polarizability usually refers to the tendency of matter, when subjected to an electric field, to acquire an electric dipole moment in proportion to that applied field. It is a property of all matter, considering that matter is made up of elementary particles which have an electric charge, namely protons and electrons. When subject to an electric field, the negatively charged electrons and positively charged atomic nuclei are subject to opposite forces and undergo charge separation. Polarizability is responsible for a material's dielectric constant and, at high (optical) frequencies, its refractive index.

An electrostatic motor or capacitor motor is a type of electric motor based on the attraction and repulsion of electric charge.

Magnetic force microscopy (MFM) is a variety of atomic force microscopy, in which a sharp magnetized tip scans a magnetic sample; the tip-sample magnetic interactions are detected and used to reconstruct the magnetic structure of the sample surface. Many kinds of magnetic interactions are measured by MFM, including magnetic dipole–dipole interaction. MFM scanning often uses non-contact AFM (NC-AFM) mode.

In classical electromagnetism, magnetization is the vector field that expresses the density of permanent or induced magnetic dipole moments in a magnetic material. Movement within this field is described by direction and is either Axial or Diametric. The origin of the magnetic moments responsible for magnetization can be either microscopic electric currents resulting from the motion of electrons in atoms, or the spin of the electrons or the nuclei. Net magnetization results from the response of a material to an external magnetic field. Paramagnetic materials have a weak induced magnetization in a magnetic field, which disappears when the magnetic field is removed. Ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials have strong magnetization in a magnetic field, and can be magnetized to have magnetization in the absence of an external field, becoming a permanent magnet. Magnetization is not necessarily uniform within a material, but may vary between different points. Magnetization also describes how a material responds to an applied magnetic field as well as the way the material changes the magnetic field, and can be used to calculate the forces that result from those interactions. It can be compared to electric polarization, which is the measure of the corresponding response of a material to an electric field in electrostatics. Physicists and engineers usually define magnetization as the quantity of magnetic moment per unit volume. It is represented by a pseudovector M.

In chemistry, a non-covalent interaction differs from a covalent bond in that it does not involve the sharing of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions between molecules or within a molecule. The chemical energy released in the formation of non-covalent interactions is typically on the order of 1–5 kcal/mol. Non-covalent interactions can be classified into different categories, such as electrostatic, π-effects, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects.

In molecular physics/nanotechnology, electrostatic deflection is the deformation of a beam-like structure/element bent by an electric field. It can be due to interaction between electrostatic fields and net charge or electric polarization effects. The beam-like structure/element is generally cantilevered. In nanomaterials, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are typical ones for electrostatic deflections.

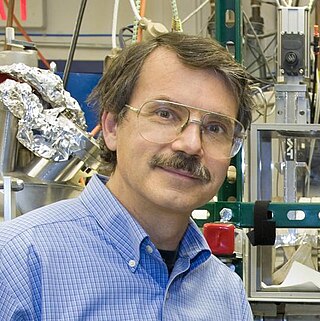

Alex K. Zettl is an American experimental physicist, educator, and inventor.

Nanomechanics is a branch of nanoscience studying fundamental mechanical properties of physical systems at the nanometer scale. Nanomechanics has emerged on the crossroads of biophysics, classical mechanics, solid-state physics, statistical mechanics, materials science, and quantum chemistry. As an area of nanoscience, nanomechanics provides a scientific foundation of nanotechnology.

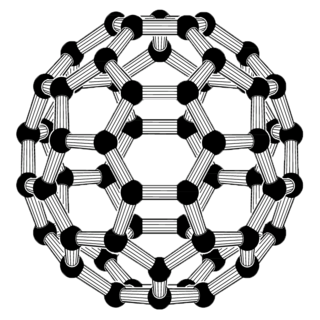

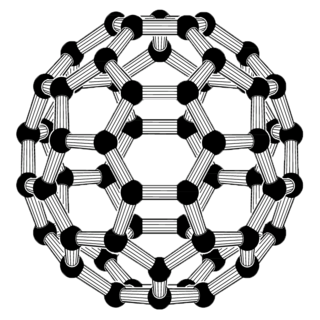

The mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reveal them as one of the strongest materials in nature. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are long hollow cylinders of graphene. Although graphene sheets have 2D symmetry, carbon nanotubes by geometry have different properties in axial and radial directions. It has been shown that CNTs are very strong in the axial direction. Young's modulus on the order of 270 - 950 GPa and tensile strength of 11 - 63 GPa were obtained.

A device generating linear or rotational motion using carbon nanotube(s) as the primary component, is termed a nanotube nanomotor. Nature already has some of the most efficient and powerful kinds of nanomotors. Some of these natural biological nanomotors have been re-engineered to serve desired purposes. However, such biological nanomotors are designed to work in specific environmental conditions. Laboratory-made nanotube nanomotors on the other hand are significantly more robust and can operate in diverse environments including varied frequency, temperature, mediums and chemical environments. The vast differences in the dominant forces and criteria between macroscale and micro/nanoscale offer new avenues to construct tailor-made nanomotors. The various beneficial properties of carbon nanotubes makes them the most attractive material to base such nanomotors on.

A carbon nanotube field-effect transistor (CNTFET) is a field-effect transistor that utilizes a single carbon nanotube or an array of carbon nanotubes as the channel material instead of bulk silicon in the traditional MOSFET structure. First demonstrated in 1998, there have been major developments in CNTFETs since.

The Research Institute for Nuclear Problems of Belarusian State University is a research institute in Minsk, Belarus. Its main fields of research are nuclear physics, particle physics, materials science and nanotechnology.

The index of physics articles is split into multiple pages due to its size.

Vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays (VANTAs) are a unique microstructure consisting of carbon nanotubes oriented with their longitudinal axis perpendicular to a substrate surface. These VANTAs effectively preserve and often accentuate the unique anisotropic properties of individual carbon nanotubes and possess a morphology that may be precisely controlled. VANTAs are consequently widely useful in a range of current and potential device applications.