Significance

Along with Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia , this was one of the earliest cases establishing the right in the U.S. of nontheistic institutions that function like traditional theistic religious institutions to be treated similarly to theistic religious institutions under the law.

Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia, 249 F.2d 127 (1957), was a case of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The Washington Ethical Society functions much like a church, but regards itself as a non-theistic religious institution, honoring the importance of ethical living without mandating a belief in a supernatural origin for ethics. The case involved denial of the Society's application for tax exemption as a religious organization. The D.C. Circuit reversed the ruling of the Tax Court for the District Columbia and found that the Society was a religious organization under the Distinct of Columbia Code, 47-801a (1951). The Society thus was granted its tax exemption.

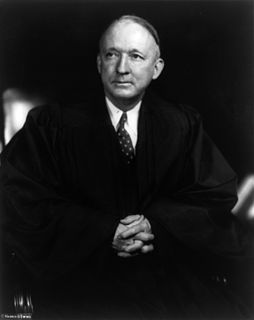

This case was cited by Justice Hugo Black in the decision for Torcaso v. Watkins , in an obiter dictum listing "secular humanism" as being among "religions in this country which do not teach what would generally be considered a belief in the existence of God."

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is the title of all members of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the Chief Justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869.

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist who served in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. A member of the Democratic Party and a devoted New Dealer, Black endorsed Franklin D. Roosevelt in both the 1932 and 1936 presidential elections. Having gained a reputation in the Senate as a reformer, Black was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Roosevelt and confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 63 to 16. He was the first of nine Roosevelt nominees to the Court, and he outlasted all except for William O. Douglas.

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (1961), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court reaffirmed that the United States Constitution prohibits States and the Federal Government from requiring any kind of religious test for public office, in the specific case, as a notary public.

The Fellowship of Humanity case itself referred to humanism but did not mention the term secular humanism. Nonetheless, this case was cited by Justice Black to justify the inclusion of Secular Humanism in the list of religions in his note. Presumably Justice Black added the word secular to emphasize the non-theistic nature of the Fellowship of Humanity and distinguish their brand of humanism from that associated with, for example, Christian humanism.

Secular humanism, or simply humanism, is a philosophy or life stance that embraces human reason, ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, pseudoscience, and superstition as the basis of morality and decision making.

Christian humanism regards humanist principles like universal human dignity and individual freedom and the primacy of human happiness as essential and principal components of the teachings of Jesus, and explicitly emerged during the Renaissance with strong roots in the patristic period. Historically, major forces shaping the development of Christian humanism was the Christian doctrine that God, in the form of Jesus Christ became human in order to redeem humanity, and the further injunction for the participating human collective to act out the life of Christ. Many of these ideas had emerged among the patristics, and would develop into Christian humanism in the late 15th century, through which the ideals of "common humanity, universal reason, freedom, personhood, human rights, human emancipation and progress, and indeed the very notion of secularity are literally unthinkable without their Christian humanistic roots." Though there is a common association of humanism with agnosticism and atheism in popular culture, this association developed in the 20th century and non-humanistic forms of agnosticism and atheism have long existed.

Black's statement was somewhat misleading in that Fellowship of Humanity v. County of Alameda did not address the question of whether the secular humanist ideas of the Fellowship of Humanity were religious; it merely determined that Fellowship of Humanity functioned like a church and so was entitled to similar protections. Subsequent cases such as Peloza v. Capistrano School District have clarified that "neither the Supreme Court, nor this circuit, has ever held that evolutionism or secular humanism are 'religions' for Establishment Clause purposes." Unlike the question of tax exemption, Establishment Clause issues rest on whether or not ideas themselves are primarily religious.

Peloza v. Capistrano Unified School District, 37 F.3d 517, was a 1994 court case heard by United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in which a creationist schoolteacher, John E. Peloza claimed that Establishment clause of the United States Constitution along with his own right to free speech was violated by the requirement to teach the "religion" of "evolutionism". The court found against Peloza, finding that evolution was science not religion and that the Capistrano Unified School District school board were right to restrict his teaching of creationism in light of the 1987 Supreme Court decision Edwards v. Aguillard. One of the three appeals judges, Poole, partially dissented from the majority's free speech and due process opinions. It was one in a long line court cases involving the teaching of creationism which have found against creationists. Peloza appealed to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

The decision for a subsequent case, Kalka v. Hawk et al., offered this commentary:

- The Court's statement in Torcaso does not stand for the proposition that humanism, no matter in what form and no matter how practiced, amounts to a religion under the First Amendment. The Court offered no test for determining what system of beliefs qualified as a "religion" under the First Amendment. The most one may read into the Torcaso footnote is the idea that a particular non-theistic group calling itself the "Fellowship of Humanity" qualified as a religious organization under California law.