The fortifications of Metz, a city in northeastern France, are extensive, due to the city's strategic position near the border of France and Germany. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the area was annexed by the newly created German Empire in 1871 by the Treaty of Frankfurt and became the Reichsland Alsace–Lorraine. The German Army decided to build a fortress line from Mulhouse to Luxembourg to protect their new territories. The centerpiece of this line was the Moselstellung between Metz and Thionville, in Lorraine.

Ouvrage Métrich located in the village of Kœnigsmacker in Moselle, comprises part of the Elzange portion of the Fortified Sector of Thionville of the Maginot Line. A gros ouvrage, it is the third largest of the Line, after Hackenberg and Hochwald. It lies between petit ouvrage Sentzich and gros ouvrage Billig, facing Germany. Located to the east of the Moselle, it cooperated with Ouvrage Galgenberg to control the river valley.

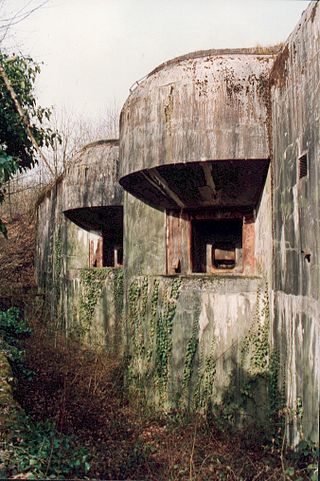

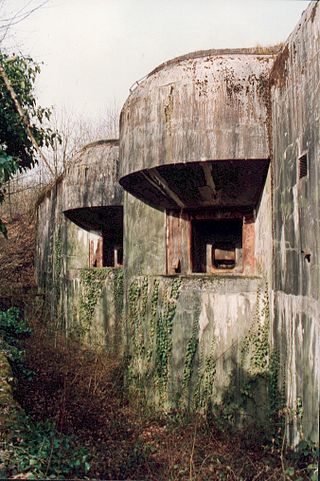

Ouvrage Sentzich is part of the Fortified Sector of Thionville of the Maginot Line. The petit ouvrage for infantry is located to the south of gros ouvrage Galgenberg, on the edge of the main road to Luxembourg near the village of Sentzich. Gros ouvrage Métrich is to the east. As a small work, it was not considered for use after World War II and was abandoned. It is secured and is not open to the public.

Ouvrage Galgenberg forms a portion of the Fortified Sector of Thionville of the Maginot Line. It is situated in the Cattenom Forest, near the gros ouvrage Kobenbusch and petit ouvrage Oberheid. The ouvrage was tasked with controlling the Moselle Valley and as such was called the "Guardian of the Moselle." Galgenberg did not see significant action in 1940 or 1944. After a period of reserve duty in the 1950s and 1960s, it was deactivated. It is now a museum.

The Fort de Guentrange dominates Thionville in the Moselle department of France. It was built by Germany next to the town of the same name in the late 19th century after the annexation of the Moselle following the Franco-Prussian War. The Fort de Guentrange was part of the Moselstellung, a group of eleven fortresses surrounding Thionville and Metz to guard against the possibility of a French attack aimed at regaining Alsace and Lorraine, with construction taking place between 1899 and 1906. The fortification system incorporated new principles of defensive construction to deal with advances in artillery. Later forts, such as Guentrange, embodied innovative design concepts such as dispersal and concealment. The later forts were designed to support offensive operations, as an anchor for a pivoting move by German forces into France.

The Fort de Koenigsmacker is a fortification located to the northeast of Thionville in the Moselle department of France. It was built by Germany next to the town of the same name in the early 20th century after the annexation of the Moselle following the Franco-Prussian War. The Fort de Koenigsmacker was part of the Moselstellung, a group of eleven fortresses surrounding Thionville and Metz to guard against the possibility of a French attack aimed at regaining Alsace and Lorraine, with construction taking place between 1908 and 1914. The fortification system incorporated new principles of defensive construction to deal with advances in artillery. Later forts, such as Koenigsmacker, embodied innovative design concepts such as dispersal and concealment. These later forts were designed to support offensive operations, as an anchor for a pivoting move by German forces into France.

Fort Jeanne d'Arc, also called Fortified Group Jeanne d'Arc, is a fortification located to the west of Metz in the Moselle department of France. It was built by Germany to the west of the town of Rozérieulles in the early 20th century as part of the third and final group of Metz fortifications. The fortification program was started after the German victory of the Franco-Prussian War, which resulted in the annexation of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine from France to Germany. The Fort Jeanne d'Arc was part of the Moselstellung, a group of eleven fortresses surrounding Thionville and Metz to guard against the possibility of a French attack aimed at regaining Alsace and Lorraine, with construction taking place between 1899 and 1908. The fortification system incorporated new principles of defensive construction to deal with advances in artillery. Later forts, such as Jeanne d'Arc, embodied innovative design concepts such as dispersal and concealment. These later forts were designed to support offensive operations, as an anchor for a pivoting move by German forces into France.

The Fort de Plappeville, or Feste Alvensleben, is a military fortification located to the northwest of Metz in the commune of Plappeville. As part of the first ring of the fortifications of Metz, it is an early example of a Séré de Rivières system fort. While it did not see action during World War I, it was the scene of heavy fighting between American forces and German defenders at the end of the Battle of Metz, in 1944. After Second World War it became a training center for the French Air Force. Fort 'Alvensleben' has been abandoned since 1995.

The Fortified Sector of Thionville was the French military organisation that in 1940 controlled the section of the Maginot Line immediately to the north of Thionville. The sector describes an arc of about 25 kilometres (16 mi), about halfway between the French border with Luxembourg and Thionville. The Thionville sector was the strongest of the Maginot Line sectors. It was surrounded but not seriously attacked in 1940 by German forces in the Battle of France, whose main objective was the city of Metz. Despite the withdrawal of the mobile forces that supported the fixed fortifications, the sector successfully fended off German assaults before the Second Armistice at Compiègne. The majority of the positions and their garrisons finally surrendered on 27 June 1940, the remainder on 2 July. Following the war, many positions were reactivated for use during the Cold War. Four locations are now preserved and open to the public.

The Fortified Sector of Faulquemont was the French military organization that in 1940 controlled the section of the Maginot Line in the area of Faulquemont to the east of Metz. With five petit ouvrages the sector was poorly equipped with fortress artillery, limiting the ouvrages ability to provide mutual support. The sector was attacked in 1940 by German forces in the Battle of France. Despite the withdrawal of the mobile forces that supported the fixed fortifications, the sector mounted a strong resistance. Two of the petit ouvrages fell to German attack, the remainder holding out until the Second Armistice at Compiègne. The surviving positions and their garrisons finally surrendered on 2 June 1940. During the Cold War, Ouvrage Kerfent was partially reactivated as a communications station for Royal Canadian Air Force units stationed in northwestern France with NATO. At present, most of the underground works in the sector are flooded by groundwater. Only Ouvrage Bambesch has been preserved and may be toured by the public.

The Fortified Sector of Boulay was the French military organization that in 1940 controlled the section of the Maginot Line to the north and east of Metz in northeastern France. The left (western) wing of the Boulay sector was among the earliest and strongest portions of the Maginot Line. The right wing, started after 1931, was progressively scaled back in order to save money during the Great Depression. It was attacked in 1940 by German forces in the Battle of France. Despite the withdrawal of the mobile forces that supported the fixed fortifications, the sector successfully fended off German assaults before the Second Armistice at Compiègne. The positions and their garrisons finally surrendered on 27 June 1940. Following the war many positions were reactivated for use during the Cold War. Three locations are now preserved and open to the public.

The Feste Kameke, renamed Fort Déroulède by the French in 1919, is a military installation near Metz. It is part of the first fortified belt of forts of Metz and had its baptism of fire in late 1944, in the Battle of Metz.

The Feste Wagner, renamed Group Fortifications of Aisne by the French in 1919, is a fort of the second fortified belt of forts from Metz, in Moselle. This group fortification, built in the municipalities of Pournoy-la-Grasse and of Verny, controlled the valley of the Seille. It had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Feste Leipzig, renamed Group Fortifications Francois-de-Guise after 1919 by the French, is a military structure located in the municipality of Châtel-Saint-Germain, close to Metz. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz and had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Feste Lothringen, renamed Group Fortification Lorraine after 1919, is a military installation near Metz. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz and had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Feste Mercy, renamed Feste Freiherr von der Goltz in 1911 and then The Group Fortification Marne in 1919, is a military installation near Metz, in the woods between Jury, Mercy and Ars-Laquenexy. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz and had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Feste Haeseler, renamed Group Fortification Verdun after 1919, is a military installation near Metz. Constituted as forts Sommy and Saint-Blaise, the fortified group is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz. It had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Feste Prinz Regent Luitpold, renamed Group Fortification Yser after 1919, is a military installation near Metz. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz and had its baptism of fire in late 1944, when the Battle of Metz occurred.

The Infanterie-Werk Belle-Croix, renamed Fort Lauvallière after 1919, is a military installation near Metz. It is part of the second fortified belt of forts of Metz.

The forts of Metz are two fortified belts around the city of Metz in Lorraine. Built according to the design and theory of Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières at the end of the Second Empire—and later Hans von Biehler while Metz was under German control—they earned the city the reputation of premier stronghold of the German reich. These fortifications were particularly thorough given the city's strategic position between France and Germany. The detached forts and fortified groups of the Metz area were spared in World War I, but showed their full defensive potential in the Battle of Metz at the end of World War II.