Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles was a British colonial official who served as Governor of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816 and Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen between 1818 and 1824. Raffles was heavily involved in the capture of the Indonesian island of Java from the Dutch during the Napoleonic Wars. It was subsequently returned under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814. He also wrote The History of Java in 1817, describing the history of the island from ancient times.

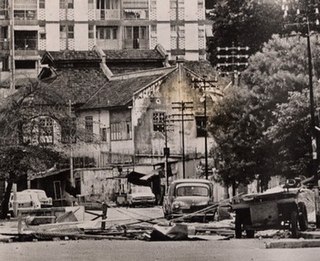

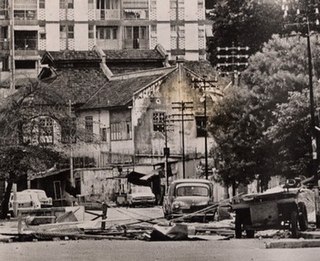

The 13 May incident was an episode of Sino-Malay sectarian violence that took place in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, on 13 May 1969. The riot occurred in the aftermath of the 1969 Malaysian general election when opposition parties such as the Democratic Action Party and Gerakan made gains at the expense of the ruling coalition, the Alliance Party.

William Farquhar was a Scottish colonial administrator employed by the East India Company, who served as the sixth Resident of Malacca between 1813 and 1818, and the first Resident of Singapore between 1819 and 1823.

The Jackson Plan or Raffles Town Plan, an urban plan of 1822 titled "Plan of the Town of Singapore", is a proposed scheme for Singapore drawn up to maintain some order in the urban development of the fledgling but thriving colony founded just three years earlier. It was named after Lieutenant Philip Jackson, the colony's engineer and land surveyor tasked to oversee its physical development in accordance with the vision of Stamford Raffles for Singapore, hence it is also commonly called Raffles Town Plan. Raffles gave his instructions in November 1822, the plan was then drawn up in late 1822 or early 1823 and published in 1828. It is the earliest extant plan for the town of Singapore, but not an actual street map of Singapore as it existed in 1822 or 1827 since the plan is an idealised scheme of how Singapore may be organised that was not fully realised. Nevertheless, it served as a guide for the development of Singapore in its early days, and the effect of the general layout of the plan is still observable to this day.

The establishment of a British trading post in Singapore in 1819 by Sir Stamford Raffles led to its founding as a British colony in 1824. This event has generally been understood to mark the founding of colonial Singapore, a break from its status as a port in ancient times during the Srivijaya and Majapahit eras, and later, as part of the Sultanate of Malacca and the Johor Sultanate.

Secret societies in Singapore have been largely eradicated as a security issue in the city-state. However many smaller groups remain today which attempt to mimic societies of the past. The membership of these societies is largely adolescent.

The Ghee Hin Kongsi was a secret society in Singapore and Malaya, formed in 1820. Ghee Hin literally means "the rise of righteousness" in Chinese and was part of the Hongmen overseas network. The Ghee Hin often fought against the Hakka-dominated Hai San secret society.

Fort Canning Hill, formerly Government Hill, Singapore Hill and Bukit Larangan, or simply known as Fort Canning, is a prominent hill, about 48 metres (157 ft) high, in the southeast portion of Singapore, within the Central Area that forms Singapore's central business district.

The history of the modern state of Singapore dates back to its founding in the early 19th century; however, evidence suggests that a significant trading settlement existed on the island in the 14th century. The last ruler of the Kingdom of Singapura, Parameswara, was expelled by the Majapahit or the Siamese before he founded Malacca. Singapore then came under the Malacca Sultanate and subsequently the Johor Sultanate. In 1819, British statesman Stamford Raffles negotiated a treaty whereby Johor will allow the British to locate a trading port on the island, ultimately leading to the establishment of the Crown colony of Singapore in 1867. Important reasons for the rise of Singapore were its nodal position at the tip of the Malay Peninsula flanked by the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the presence of a natural sheltered harbour, as well as its status as a free port.

Singapore in the Straits Settlements refers to a period in the history of Singapore between 1826 and 1942, during which Singapore was part of the Straits Settlements together with Penang and Malacca. Singapore was the capital and the seat of government of the Straits Settlement after it was moved from George Town in 1832.

The Larut Wars were a series of four wars started in July 1861 and ended with the signing of the Pangkor Treaty of 1874. The conflict was fought among local Chinese secret societies over the control of mining areas in Perak which later involved rivalry between Raja Abdullah and Ngah Ibrahim, making it a war of succession.

Anti-Malay sentiment or Malayophobia refers to feelings of hostility, prejudice, discrimination or disdain towards Malay people, Malay culture, the Malay language or anything perceived as Malay.

The Hai San Society, which had its origins in Southern China, was a Penang-based Chinese secret society established around 1820 and in 1825 led by Low, Ah Chong and Hoh Akow, its titular head. At that time the society's headquarters was located at Beach Street.

Khoo Thean Teik was one of the most powerful and notorious Hokkien leaders of 19th-century Penang. His name, "Thean Teik", means "Heavenly Virtue". He was the leader of the Tokong or Khian Teik society that was involved in the Penang Riots of 1867 and through its connection with the Hai San, the internecine Larut Wars of 1861 to 1874. He traded through the companies Khoon Ho and Chin Bee. He was a towkay, trading in immigrant labour and had interests in the Opium Farms in Penang and Hong Kong. Thean Teik Estate, a residential neighbourhood in Penang, and Jalan Thean Teik are named after him.

Kapitan Cina, also spelled Kapitan China or Capitan China, was a high-ranking government position in the civil administration of colonial Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Borneo and the Philippines. Office holders exercised varying degrees of power and influence: from near-sovereign political and legal jurisdiction over local Chinese communities, to ceremonial precedence for community leaders. Corresponding posts existed for other ethnic groups, such as Kapitan Arab and Kapitan Keling for the local Arab and Indian communities respectively.

Ngee Heng Kongsi of Johor was a Teochew secret society that founded the earliest Chinese settlement in Johor. However, it did not have a clandestine image and has instead been accorded a respectable place in the history of the Johor Chinese. The term kongsi generally refers to any firm or partnership, and has also been used to refer to any group or society in a very broad sense. Ngee Heng is the Teochew name for the Ghi Hin or Ghee Hin, its name in Hokkien. The name identifies it as the Teochew offshoot of the Tiandihui secret society.

Singaporeans are an ethnic group comprising citizens who identify themselves as a nation with the sovereign island city-state of Singapore. Singapore is a multi-racial, multi-cultural, multi-religious, and multi-lingual country. Singaporeans of Chinese, Malay, Indian and Eurasian descent have made up the vast majority of the population since the 19th century. The Singaporean diaspora is also far-reaching worldwide.

The coming of the British to Singapore and the subsequent establishment of British rule saw the rise of secret societies in this small colony. Whilst known as "secret" societies, paradoxically they often worked in the open, and even played essential and functional roles within society, with state knowledge or tacit cooperation.

Organised crime in Singapore has a long history with secret societies such as Ghee Hin Kongsi carrying out their activities in the 19th century. These organized groups hold great relevance to Singaporean modern history. Since 1890, organized groups began fading from Singapore, decline in street organized crime in the past years due to legislation has been put place to ensure authorities suppress the activities of criminal gangs. Contemporary Singapore witnessed a significant rise in other forms of crime —organised cyber-crime.