Organizational culture refers to culture related to organizations including schools, universities, not-for-profit groups, government agencies, and business entities. Alternative terms include corporate culture and company culture. The term corporate culture emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was used by managers, sociologists, and organizational theorists in the 1980s.

Gerard Hendrik (Geert) Hofstede was a Dutch social psychologist, IBM employee, and Professor Emeritus of Organizational Anthropology and International Management at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, well known for his pioneering research on cross-cultural groups and organizations.

Alfonsus (Fons) Trompenaars is a Dutch organizational theorist, management consultant, and author in the field of ethics. known for the development of Trompenaars' model of national culture differences and Dilemma Theory.

Cross-cultural studies, sometimes called holocultural studies or comparative studies, is a specialization in anthropology and sister sciences such as sociology, psychology, economics, political science that uses field data from many societies through comparative research to examine the scope of human behavior and test hypotheses about human behavior and culture.

In cross-cultural psychology, uncertainty avoidance is how cultures differ on the amount of tolerance they have of unpredictability. Uncertainty avoidance is one of five key qualities or dimensions measured by the researchers who developed the Hofstede model of cultural dimensions to quantify cultural differences across international lines and better understand why some ideas and business practices work better in some countries than in others.According to Geert Hofstede, "The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: Should we try to control it or just let it happen?"

Power distance is the unequal distribution of power between parties, and the level of acceptance of that inequality; whether it is in the family, workplace, or other organizations.

Japanese values are cultural goals, beliefs and behaviors that are considered important in Japanese culture. From a global perspective, Japanese culture stands out for its higher scores in emancipative values, individualism, and flexibility compared to many other cultures around the world. There is a similar level of emphasis on these values in the cultures of the United States and Japan. However cultures from Western Europe surpass it in these aspects. Overall, Japanese society exhibits unique characteristics influenced by personal connections, consensus building, and a strong sense of community consciousness. These features have deep historical roots and reflect the values ingrained in Japanese society.

Cultural competence, also known as intercultural competence, is a range of cognitive, affective, behavioural, and linguistic skills that lead to effective and appropriate communication with people of other cultures. Intercultural or cross-cultural education are terms used for the training to achieve cultural competence.

Cultural economics is the branch of economics that studies the relation of culture to economic outcomes. Here, 'culture' is defined by shared beliefs and preferences of respective groups. Programmatic issues include whether and how much culture matters as to economic outcomes and what its relation is to institutions. As a growing field in behavioral economics, the role of culture in economic behavior is increasingly being demonstrated to cause significant differentials in decision-making and the management and valuation of assets.

Cross-cultural psychology is the scientific study of human behavior and mental processes, including both their variability and invariance, under diverse cultural conditions. Through expanding research methodologies to recognize cultural variance in behavior, language, and meaning it seeks to extend and develop psychology. Since psychology as an academic discipline was developed largely in North America and Europe, some psychologists became concerned that constructs and phenomena accepted as universal were not as invariant as previously assumed, especially since many attempts to replicate notable experiments in other cultures had varying success. Since there are questions as to whether theories dealing with central themes, such as affect, cognition, conceptions of the self, and issues such as psychopathology, anxiety, and depression, may lack external validity when "exported" to other cultural contexts, cross-cultural psychology re-examines them using methodologies designed to factor in cultural differences so as to account for cultural variance. Some critics have pointed to methodological flaws in cross-cultural psychological research, and claim that serious shortcomings in the theoretical and methodological bases used impede, rather than help the scientific search for universal principles in psychology. Cross-cultural psychologists are turning more to the study of how differences (variance) occur, rather than searching for universals in the style of physics or chemistry.

Face negotiation theory is a theory conceived by Stella Ting-Toomey in 1985, to understand how people from different cultures manage rapport and disagreements. The theory posited "face", or self-image when communicating with others, as a universal phenomenon that pervades across cultures. In conflicts, one's face is threatened; and thus the person tends to save or restore his or her face. This set of communicative behaviors, according to the theory, is called "facework". Since people frame the situated meaning of "face" and enact "facework" differently from one culture to the next, the theory poses a cross-cultural framework to examine facework negotiation. It is important to note that the definition of face varies depending on the people and their culture and the same can be said for the proficiency of facework. According to Ting-Toomey's theory, most cultural differences can be divided by Eastern and Western cultures, and her theory accounts for these differences.

Philippe d’Iribarne is a French author and director of research at CNRS. He works within a research centre called LISE.

Cross-cultural psychology attempts to understand how individuals of different cultures interact with each other. Along these lines, cross-cultural leadership has developed as a way to understand leaders who work in the newly globalized market. Today's international organizations require leaders who can adjust to different environments quickly and work with partners and employees of other cultures. It cannot be assumed that a manager who is successful in one country will be successful in another.

Global leadership is the interdisciplinary study of the key elements that future leaders in all realms of the personal experience should acquire to effectively familiarize themselves with the psychological, physiological, geographical, geopolitical, anthropological and sociological effects of globalization. Global leadership occurs when an individual or individuals navigate collaborative efforts of different stakeholders through environmental complexity towards a vision by leveraging a global mindset. Today, global leaders must be capable of connecting "people across countries and engage them to global team collaboration in order to facilitate complex processes of knowledge sharing across the globe" Personality characteristics, as well as a cross-cultural experience, appear to influence effectiveness in global leaders.

Individualistic cultures are characterized by individualism, which is the prioritization or emphasis of the individual over the entire group. In individualistic cultures people are motivated by their own preference and viewpoints. Individualistic cultures focus on abstract thinking, privacy, self-dependence, uniqueness, and personal goals. The term individualistic culture was first used in the 1980s by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede to describe countries and cultures that are not collectivist, Hofstede created the term individualistic culture when he created a measurement for the five dimensions of cultural values.

Cultural communication is the practice and study of how different cultures communicate within their community by verbal and nonverbal means. Cultural communication can also be referred to as intercultural communication and cross-cultural communication. Cultures are grouped together by a set of similar beliefs, values, traditions, and expectations which call all contribute to differences in communication between individuals of different cultures. Cultural communication is a practice and a field of study for many psychologists, anthropologists, and scholars. The study of cultural communication is used to study the interactions of individuals between different cultures. Studies done on cultural communication are utilized in ways to improve communication between international exchanges, businesses, employees, and corporations. Two major scholars who have influenced cultural communication studies are Edward T. Hall and Geert Hofstede. Edward T. Hall, who was an American anthropologist, is considered to be the founder of cultural communication and the theory of proxemics. The theory of proxemics focuses on how individuals use space while communicating depending on cultural backgrounds or social settings. The space in between individuals can be identified in four different ranges. For example, 0 inches signifies intimate space while 12 feet signifies public space. Geert Hofstede was a social psychologist who founded the theory of cultural dimension. In his theory, there are five dimensions that aim to measure differences between different cultures. The five dimensions are power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, and Chronemics.

Robert Roger McCrae is a personality psychologist. He earned his Ph.D. in 1976, and worked at the National Institute of Aging. He is associated with the Five Factor Theory of personality. He has spent his career studying the stability of personality across age and culture. Along with Paul Costa, he is a co-author of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. He has served on the editorial boards of many scholarly journals, including the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the Journal of Research in Personality, the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, and the Journal of Individual Differences.

Trompenaars's model of national culture differences is a framework for cross-cultural communication applied to general business and management, developed by Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner. This involved a large-scale survey of 8,841 managers and organization employees from 43 countries.

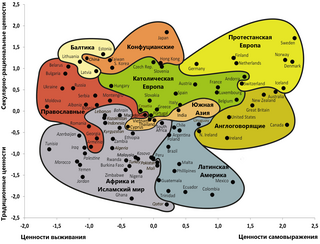

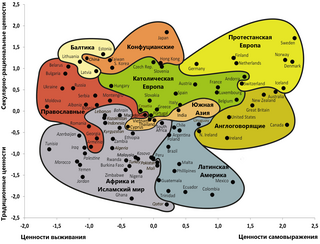

The Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world is a scatter plot created by political scientists Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel based on the World Values Survey and European Values Survey. It depicts closely linked cultural values that vary between societies in two predominant dimensions: traditional versus secular-rational values on the vertical y-axis and survival versus self-expression values on the horizontal x-axis. Moving upward on this map reflects the shift from traditional values to secular-rational ones and moving rightward reflects the shift from survival values to self-expression values.

Culture can affect aviation safety through its effect on how the flight crew deals with difficult situations; cultures with lower power distances and higher levels of individuality can result in better aviation safety outcomes. In higher power cultures subordinates are less likely to question their superiors. The crash of Korean Air Flight 801 in 1997 was attributed to the pilot's decision to land despite the junior officer's disagreement, while the crash of Avianca Flight 052 was caused by the failure to communicate critical low-fuel data between pilots and controllers, and by the failure of the controllers to ask the pilots if they were declaring an emergency and assist the pilots in landing the aircraft. The crashes have been blamed on aspects of the national cultures of the crews.