Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not only transmits meaning but also creates it. Models of communication are simplified overviews of its main components and their interactions. Many models include the idea that a source uses a coding system to express information in the form of a message. The message is sent through a channel to a receiver who has to decode it to understand it. The main field of inquiry investigating communication is called communication studies.

Harold Dwight Lasswell was an American political scientist and communications theorist. He earned his bachelor's degree in philosophy and economics and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He was a professor of law at Yale University. He served as president of the American Political Science Association, American Society of International Law, and World Academy of Art and Science.

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself or self-to-self communication. Examples are thinking to oneself "I will do better next time" after having made a mistake or imagining a conversation with one's boss in preparation for leaving work early. It is often understood as an exchange of messages in which the sender and the receiver is the same person. Some theorists use a wider definition that goes beyond message-based accounts and focuses on the role of meaning and making sense of things. Intrapersonal communication can happen alone or in social situations. It may be prompted internally or occur as a response to changes in the environment.

Communication theory is a proposed description of communication phenomena, the relationships among them, a storyline describing these relationships, and an argument for these three elements. Communication theory provides a way of talking about and analyzing key events, processes, and commitments that together form communication. Theory can be seen as a way to map the world and make it navigable; communication theory gives us tools to answer empirical, conceptual, or practical communication questions.

The hypodermic needle model is claimed to have been a model of communication in which media consumers were "uniformly controlled by their biologically based 'instincts' and that they react more or less uniformly to whatever 'stimuli' came along".

Uses and gratifications theory is a communication theory that describes the reasons and means by which people seek out media to meet specific needs. The theory postulates that media is a highly available product, that audiences are the consumers of the product, and that audiences choose media to satisfy given needs as well as social and psychological uses, such as knowledge, relaxation, social relationships, and diversion.

Denis McQuail was a British communication theorist, Emeritus Professor at the University of Amsterdam, considered one of the most influential scholars in the field of mass communication studies.

In media studies, mass communication, media psychology, communication theory, and sociology, media influence and themedia effect are topics relating to mass media and media culture's effects on individuals' or audiences' thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. Through written, televised, or spoken channels, mass media reach large audiences. Mass media's role in shaping modern culture is a central issue for the study of culture.

Audience theory offers explanations of how people encounter media, how they use it, and how it affects them. Although the concept of an audience predates media, most audience theory is concerned with people’s relationship to various forms of media. There is no single theory of audience, but a range of explanatory frameworks. These can be rooted in the social sciences, rhetoric, literary theory, cultural studies, communication studies and network science depending on the phenomena they seek to explain. Audience theories can also be pitched at different levels of analysis ranging from individuals to large masses or networks of people.

The Shannon–Weaver model is one of the first and most influential models of communication. It was initially published in the 1948 paper A Mathematical Theory of Communication and explains communication in terms of five basic components: a source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination. The source produces the original message. The transmitter translates the message into a signal, which is sent using a channel. The receiver translates the signal back into the original message and makes it available to the destination. For a landline phone call, the person calling is the source. They use the telephone as a transmitter, which produces an electric signal that is sent through the wire as a channel. The person receiving the call is the destination and their telephone is the receiver.

The encoding/decoding model of communication was first developed by cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall in 1973. Stuart Hall titled the study 'Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse.' Hall's essay offers a theoretical approach of how media messages are produced, disseminated, and interpreted. Hall proposed that audience members can play an active role in decoding messages as they rely on their own social contexts and capability of changing messages through collective action.

In mathematics, computer science, telecommunication, information theory, and searching theory, error-correcting codes with feedback are error correcting codes designed to work in the presence of feedback from the receiver to the sender.

Social information processing theory, also known as SIP, is a psychological and sociological theory originally developed by Salancik and Pfeffer in 1978. This theory explores how individuals make decisions and form attitudes in a social context, often focusing on the workplace. It suggests that people rely heavily on the social information available to them in their environments, including input from colleagues and peers, to shape their attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions.

The hyperpersonal model is a model of interpersonal communication that suggests computer-mediated communication (CMC) can become hyperpersonal because it "exceeds [face-to-face] interaction", thus affording message senders a host of communicative advantages over traditional face-to-face (FtF) interaction. The hyperpersonal model demonstrates how individuals communicate uniquely, while representing themselves to others, how others interpret them, and how the interactions create a reciprocal spiral of FtF communication. Compared to ordinary FtF situations, a hyperpersonal message sender has a greater ability to strategically develop and edit self-presentation, enabling a selective and optimized presentation of one's self to others.

Sven Windahl is a Swedish professor of communication studies as well as a consultant in the field of organizational communication. His most influential work is the book Using Communication Theory from 1989, co-authored with Dr. Benno Signitzer and Jean T. Olson. The book has been translated into many languages.

Active Audience Theory argues that media audiences do not just receive information passively but are actively involved, often unconsciously, in making sense of the message within their personal and social contexts. Decoding of a media message may therefore be influenced by such things as family background, beliefs, values, culture, interests, education and experiences. Decoding of a message means how well a person is able to effectively receive and understand a message. Active Audience Theory is particularly associated with mass-media usage and is a branch of Stuart Hall's Encoding and Decoding Model.

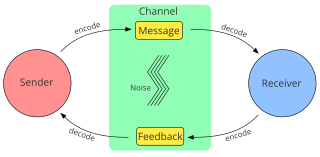

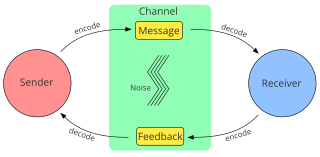

Models of communication are simplified representations of the process of communication. Most models try to describe both verbal and non-verbal communication and often understand it as an exchange of messages. Their function is to give a compact overview of the complex process of communication. This helps researchers formulate hypotheses, apply communication-related concepts to real-world cases, and test predictions. Despite their usefulness, many models are criticized based on the claim that they are too simple because they leave out essential aspects. The components and their interactions are usually presented in the form of a diagram. Some basic components and interactions reappear in many of the models. They include the idea that a sender encodes information in the form of a message and sends it to a receiver through a channel. The receiver needs to decode the message to understand the initial idea and provides some form of feedback. In both cases, noise may interfere and distort the message.

Various aspects of communication have been the subject of study since ancient times, and the approach eventually developed into the academic discipline known today as communication studies.

The source–message–channel–receiver model is a linear transmission model of communication. It is also referred to as the sender–message–channel–receiver model, the SMCR model, and Berlo's model. It was first published by David Berlo in his 1960 book The Process of Communication. It contains a detailed discussion of the four main components of communication: source, message, channel, and receiver. Source and receiver are usually distinct persons but can also be groups and, in some cases, the same entity acts both as source and receiver. Berlo discusses both verbal and non-verbal communication and sees all forms of communication as attempts by the source to influence the behavior of the receiver. The source tries to achieve this by formulating a communicative intention and encoding it in the form of a message. The message is sent to the receiver using a channel and has to be decoded so they can understand it and react to it. The efficiency or fidelity of communication is defined by the degree to which the reaction of the receiver matches the purpose motivating the source.

Schramm's model of communication is an early and influential model of communication. It was first published by Wilbur Schramm in 1954 and includes innovations over previous models, such as the inclusion of a feedback loop and the discussion of the role of fields of experience. For Schramm, communication is about sharing information or having a common attitude towards signs. His model is based on three basic components: a source, a destination, and a message. The process starts with an idea in the mind of the source. This idea is then encoded into a message using signs and sent to the destination. The destination needs to decode and interpret the signs to reconstruct the original idea. In response, they formulate their own message, encode it, and send it back as a form of feedback. Feedback is a key part of many forms of communication. It can be used to mitigate processes that may undermine successful communication, such as external noise or errors in the phases of encoding and decoding.