Related Research Articles

Gastroenterology is the branch of medicine focused on the digestive system and its disorders. The digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract, sometimes referred to as the GI tract, which includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine as well as the accessory organs of digestion which include the pancreas, gallbladder, and liver. The digestive system functions to move material through the GI tract via peristalsis, break down that material via digestion, absorb nutrients for use throughout the body, and remove waste from the body via defecation. Physicians who specialize in the medical specialty of gastroenterology are called gastroenterologists or sometimes GI doctors. Some of the most common conditions managed by gastroenterologists include gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, peptic ulcer disease, gallbladder and biliary tract disease, hepatitis, pancreatitis, colitis, colon polyps and cancer, nutritional problems, and many more.

Dietary fiber or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by their solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, which affect how fibers are processed in the body. Dietary fiber has two main components: soluble fiber and insoluble fiber, which are components of plant-based foods, such as legumes, whole grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts or seeds. A diet high in regular fiber consumption is generally associated with supporting health and lowering the risk of several diseases. Dietary fiber consists of non-starch polysaccharides and other plant components such as cellulose, resistant starch, resistant dextrins, inulin, lignins, chitins, pectins, beta-glucans, and oligosaccharides.

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the bowel movement. Complications from constipation may include hemorrhoids, anal fissure or fecal impaction. The normal frequency of bowel movements in adults is between three per day and three per week. Babies often have three to four bowel movements per day while young children typically have two to three per day.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a "disorder of gut-brain interaction" characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and changes in the consistency of bowel movements. These symptoms may occur over a long time, sometimes for years. IBS can negatively affect quality of life and may result in missed school or work or reduced productivity at work. Disorders such as anxiety, major depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome are common among people with IBS.

Colonoscopy or coloscopy is the endoscopic examination of the large bowel and the distal part of the small bowel with a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera on a flexible tube passed through the anus. It can provide a visual diagnosis and grants the opportunity for biopsy or removal of suspected colorectal cancer lesions.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of the colon and small intestine, with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine and large intestine, as well as the mouth, esophagus, stomach and the anus, whereas ulcerative colitis primarily affects the colon and the rectum.

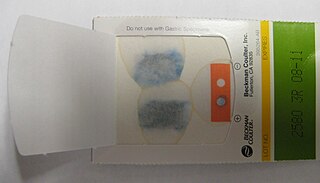

Fecal occult blood (FOB) refers to blood in the feces that is not visibly apparent. A fecal occult blood test (FOBT) checks for hidden (occult) blood in the stool (feces).

Diverticulitis, also called colonic diverticulitis, is a gastrointestinal disease characterized by inflammation of abnormal pouches—diverticula—that can develop in the wall of the large intestine. Symptoms typically include lower-abdominal pain of sudden onset, but the onset may also occur over a few days. There may also be nausea; and diarrhea or constipation. Fever or blood in the stool suggests a complication. Repeated attacks may occur.

Diverticulosis is the condition of having multiple pouches (diverticula) in the colon that are not inflamed. These are outpockets of the colonic mucosa and submucosa through weaknesses of muscle layers in the colon wall. Diverticula do not cause symptoms in most people. Diverticular disease occurs when diverticula become clinically inflamed, a condition known as diverticulitis.

Abdominal bloating is a short-term disease that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Bloating is generally characterized by an excess buildup of gas, air or fluids in the stomach. A person may have feelings of tightness, pressure or fullness in the stomach; it may or may not be accompanied by a visibly distended abdomen. Bloating can affect anyone of any age range and is usually self-diagnosed, in most cases does not require serious medical attention or treatment. Although this term is usually used interchangeably with abdominal distension, these symptoms probably have different pathophysiological processes, which are not fully understood.

Blood in stool or rectal bleeding looks different depending on how early it enters the digestive tract—and thus how much digestive action it has been exposed to—and how much there is. The term can refer either to melena, with a black appearance, typically originating from upper gastrointestinal bleeding; or to hematochezia, with a red color, typically originating from lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Evaluation of the blood found in stool depends on its characteristics, in terms of color, quantity and other features, which can point to its source, however, more serious conditions can present with a mixed picture, or with the form of bleeding that is found in another section of the tract. The term "blood in stool" is usually only used to describe visible blood, and not fecal occult blood, which is found only after physical examination and chemical laboratory testing.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, commonly abbreviated LGIB, is any form of gastrointestinal bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract. LGIB is a common reason for seeking medical attention at a hospital's emergency department. LGIB accounts for 30–40% of all gastrointestinal bleeding and is less common than upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). It is estimated that UGIB accounts for 100–200 per 100,000 cases versus 20–27 per 100,000 cases for LGIB. Approximately 85% of lower gastrointestinal bleeding involves the colon, 10% are from bleeds that are actually upper gastrointestinal bleeds, and 3–5% involve the small intestine.

Abdominal distension occurs when substances, such as air (gas) or fluid, accumulate in the abdomen causing its expansion. It is typically a symptom of an underlying disease or dysfunction in the body, rather than an illness in its own right. People with this condition often describe it as "feeling bloated". Affected people often experience a sensation of fullness, abdominal pressure, and sometimes nausea, pain, or cramping. In the most extreme cases, upward pressure on the diaphragm and lungs can also cause shortness of breath. Through a variety of causes, bloating is most commonly due to buildup of gas in the stomach, small intestine, or colon. The pressure sensation is often relieved, or at least lessened, by belching or flatulence. Medications that settle gas in the stomach and intestines are also commonly used to treat the discomfort and lessen the abdominal distension.

The specific carbohydrate diet (SCD) is a restrictive diet originally created to manage celiac disease; it limits the use of complex carbohydrates. Monosaccharides are allowed, and various foods including fish, aged cheese and honey are included. Prohibited foods include cereal grains, potatoes and lactose-containing dairy products. It is a gluten-free diet since no grains are permitted.

Capsule endoscopy is a medical procedure used to record internal images of the gastrointestinal tract for use in disease diagnosis. Newer developments are also able to take biopsies and release medication at specific locations of the entire gastrointestinal tract. Unlike the more widely used endoscope, capsule endoscopy provides the ability to see the middle portion of the small intestine. It can be applied to the detection of various gastrointestinal cancers, digestive diseases, ulcers, unexplained bleedings, and general abdominal pains. After a patient swallows the capsule, it passes along the gastrointestinal tract, taking a number of images per second which are transmitted wirelessly to an array of receivers connected to a portable recording device carried by the patient. General advantages of capsule endoscopy over standard endoscopy include the minimally invasive procedure setup, ability to visualize more of the gastrointestinal tract, and lower cost of the procedure.

A bland diet is a diet consisting of foods that are generally soft, low in dietary fiber, cooked rather than raw, and not spicy. It is an eating plan that emphasizes foods that are easy to digest. It is commonly recommended for people recovering from surgery or conditions affecting the gastrointestinal tract.

Fibre supplements are considered to be a form of a subgroup of functional dietary fibre, and in the United States are defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). According to the IOM, functional fibre "consists of isolated, non-digestible carbohydrates that have beneficial physiological effects in humans".

FODMAPs or fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and ferment in the colon. They include short-chain oligosaccharide polymers of fructose (fructans) and galactooligosaccharides, disaccharides (lactose), monosaccharides (fructose), and sugar alcohols (polyols), such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and maltitol. Most FODMAPs are naturally present in food and the human diet, but the polyols may be added artificially in commercially prepared foods and beverages.

Blair S. Lewis, M.D., F.A.C.P., F.A.C.G., is an American board-certified gastroenterologist and Clinical Professor of Medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Lewis is a specialist in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy and was the primary investigator for the first clinical trial of capsule endoscopy for the small intestine and also the first clinical trial of capsule endoscopy for the colon.

A low-FODMAP diet is a person's global restriction of consumption of all fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs), recommended only for a short time. A low-FODMAP diet is recommended for managing patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and can reduce digestive symptoms of IBS including bloating and flatulence.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Low Fiber/Low Residue Diet". ATLANTIC COAST GASTROENTEROLOGY ASSOCIATES. Atlantic Coast Gastroenterology. December 17, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Low Fiber/Low Residue Diet". Jackson|Siegelbaum Gastroenterology. Jackson|Siegelbaum Gastroenterology and West Shore Endoscopy Center. November 3, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Should You Try a Low-Residue Diet?". WebMD. October 25, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Low residue diet" (PDF). Great Western Hospital. Great Western Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. May 15, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Wax, Emily; Zieve, David; Ogilvie, Isla (August 14, 2016). "Low-fiber diet". Medline Plue. ADAM Health Solutions. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Low-Fiber Nutrition Therapy". New York Presbyterian. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Diverticulitis Diet". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. August 15, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Manual of Clinical Nutrition Management (PDF). Compass Group. 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Low FIber Diet" (PDF). Rush University Medical Center. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Clinical Dietitians Nutrition Service. "Low-Fiber, Low-Residue Diet" (PDF). Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Low-Residue/Low-Fiber Diet". University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. UPMC. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- 1 2 Vanhauwaert, Erika; Matthys, Christophe; Verdonck, Lies; De Preter, Vicky (November 2015). "Low-Residue and Low-Fiber Diets in Gastrointestinal Disease Management". Advances in Nutrition. 6 (6): 820–827. doi:10.3945/an.115.009688. PMC 4642427 . PMID 26567203 . Retrieved April 26, 2017.

This narrative review focuses on defining the similarities and/or discrepancies between low-residue and low-fiber diets and on the diagnostic and therapeutic values of these diets in gastrointestinal disease management.

- ↑ Saltzman, John R.; Cash, Brooks D.; Pasha, Shabana F.; Early, Dayna S.; Muthusamy, V. Raman; Khashab, Mouen A.; Chathadi, Krishnavel V.; Fanelli, Robert D.; Chandrasekhara, Vinay; et al. (April 2015). "Bowel preparation before colonoscopy". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 81 (4): 781–794. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.048. PMID 25595062.

This is one of a series of documents discussing the use of GI endoscopy in common clinical situations. The Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy prepared this document that updates a previously issued consensus statement and a technology status evaluation report on this topic

- ↑ Wu, Keng-Liang; Rayner, Christopher K; Chuah, Seng-Kee; Chiu, King-Wah; Lu, Chien-Chang; Chiu, Yi-Chun (2011). "Impact of low-residue diet on bowel preparation for colonoscopy". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 54 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fb1e52. PMID 21160321. S2CID 25592615.

- ↑ Helwick, Caroline (May 23, 2016). "Low-Residue Diet Acceptable for Bowel Prep". Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ↑ Alexander, Dominik D; Bylsma, Lauren C; Elkayam, Laura; Nguyen, Douglas L (May 6, 2016). "Nutritional and health benefits of semi-elemental diets: A comprehensive summary of the literature". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 7 (2): 306–319. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.306 . PMC 4848254 . PMID 27158547.

- ↑ Strate, Lisa L. "Diverticular Disease". NIH. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ↑ Tarleton, S; Dibaise, JK (January 17, 2017). "Invited Review: Low-residue diet in diverticular disease: Putting an end to a myth". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 26 (2): 137–42. doi:10.1177/0884533611399774. PMID 21447765.

- ↑ "SR-71 Pilot Interview Richard Graham Veteran Tales". YouTube . Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ↑ Alpers, David H.; Taylor, Beth E.; Bier, Dennis M.; Klein, Samuel (January 21, 2015). Manual of Nutritional Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Meant for quick retrieval of vital information regarding the management of nutritional issues in patients with gastroenterological problems--either primary or as the consequence of other medical disorders, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia and obesity. The book addresses normal physiology and pathophysiology, and offers chapters on diseases that can lead to specific nutritional problems. The clinical focus is on therapeutic nutrition and dietary management.

- ↑ Cunningham, Eleese (April 2012). "Are Low-Residue Diets Still Applicable?". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 112 (6): 960. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.04.005. PMID 22709819.