| Morgan v. United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued January 12, 1885 Decided March 2, 1885 | |

| Full case name | Morgan v. United States |

| Citations | 113 U.S. 476 ( more ) 5 S. Ct. 588; 28 L. Ed. 1044 |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Matthews, joined by unanimous |

Morgan v. United States, 113 U.S. 476 (1885), was a case involving several judgments of the United States Court of Claims in four cases against the United States for the payment of United States bonds known as "five-twenty bonds." [1]

The Court of Claims was a federal court that heard claims against the United States government. It was established in 1855, renamed in 1948 to the United States Court of Claims, and abolished in 1982. Then, its jurisdiction was assumed by the newly created United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and United States Claims Court, which was later renamed the Court of Federal Claims.

Contents

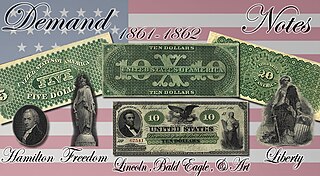

Consols of 1865, issued in pursuance of the authority conferred upon the Secretary of the Treasury by the Act of Congress approved March 3, 1865, entitled "An act to provide ways and means for the support of the government." Twenty bonds of the denomination of $1,000 each and sixteen of $500 each were embraced in the suits. The controversy relates to the title only, all of them being claimed by the Manhattan Savings Institution, and ten of each denomination by J.S. Morgan & Co., and the others, being ten of $1,000 each and six of $500 each, by L. Von Hoffman & Co. The bonds having been called in for redemption, were presented at the Treasury for that purpose by the holders, respectively, J.S. Morgan & Co. and L. Von Hoffman & Co., but payment was refused by the United States on account of the adverse claim of the Manhattan Savings Institution, and the claims of the several parties to the proceeds were Treasury, March 12, 1880, pursuant to § 1063, Revised Statutes. Judgments were rendered by that court in favor of the Manhattan Savings Institution, and against the other claimants respectively. 18 Ct.Cl. 386. The several appeals bring up all the cases as they stood in the Court of Claims; the United States appealing from the judgment in favor of the Manhattan Savings Institution, the other parties from the judgments dismissing their respective petitions. The controversy is wholly between the claimants, the United States being merely in the position of a stakeholder, not denying its liability to pay to the true owners of the bonds.

Consols was a name given to certain government debt issues in the form of perpetual bonds, redeemable at the option of the government. They were issued by the U.S. Government and the Bank of England. The first British Consols were issued in 1751. They have now been fully redeemed. The first U.S. Government Consols were issued in the 1870s.

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by the United States Congress. It can either be a Public Law, relating to the general public, or a Private Law, relating to specific institutions or individuals.

J.S. Morgan & Co. was a merchant banking firm based in London and New York City founded by Junius S. Morgan, father of J. Pierpont Morgan. The business had originally been started by the American merchant George Peabody conducting business on his own account when he took up residence in London in 1838. The business was formally incorporated as George Peabody & Co. in 1851 and on Peabody's retirement in 1864 control was assumed by Morgan who had joined the firm as a partner in 1854. As a consequence the firm was re-styled J. S. Morgan & Co.. The firm's New York agency was later to become J.P. Morgan & Co. a predecessor firm of JPMorgan Chase.

The act of Congress in pursuance of which the bonds in question were issued, being "An act to provide ways and means for the support of the government," approved March 3, 1865, 13 Stat. 468, c. 77, provided:

That the Secretary of the Treasury be, and he is hereby, authorized to borrow from time to time, on the credit of the United States, in addition to the amounts heretofore authorized, any sums not exceeding in the aggregate six hundred millions of dollars, and to issue therefor bonds or Treasury notes of the United States in such form as he may prescribe, and so much thereof as may be issued in bonds shall be of denominations not less than fifty dollars, and may be made payable at any period not more than forty years from date of issue, or may be made redeemable at the pleasure of the government at or after any period not less than five years nor more than forty years from date, or may be made redeemable and payable as aforesaid, as may be expressed upon their face,

The bonds issued under this act were called the consolidated debt or consols of 1865, because, in addition to the loan of six hundred millions of dollars authorized by it, the Secretary of the Treasury was empowered to permit the conversion, into any description of bonds authorized by it, of any Treasury notes or other obligations, bearing interest, issued under any act of Congress.

The bonds were only different only in numbers and denomination, and were in the following form:

- ~165,120] [165,120

- "[Consolidated debt. Issued under act of Congress approved March 3, 1865. Redeemable after five and payable twenty years from date.]"

- "1,000] [1,000"

- "It is hereby certified that the United States of America are indebted unto the bearer in the sum of one thousand dollars, redeemable at the pleasure of the United States after the first day of July 1870, and payable on the first day of July 1885, with interest from the first day of July 1865, inclusive at six percent per annum, payable on the first day of January and July in each year, on the presentation of the proper coupon hereunto annexed. This debt is authorized by act of Congress approved March 3, 1865."

- "Washington, July 1, 1865."

- "J. LOWERY"

- "For Register of the Treasury"

- "Six months' interest due July 1, 1885, payable with this bond."

- "(Thirteen coupons attached from and including coupon for interest due January 1, 1879, to and including coupon for interest due January 1, 1885.)"

The bonds were known as "five-twenty bonds," because they were redeemable after five years but not payable until twenty years after July 1, 1865.

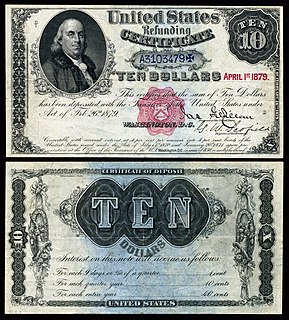

The Act of July 14, 1870, "to authorize the refunding of the national debt," 16 Stat. 272, authorized the issue of three classes of bonds, according as they bore interest at the rates of five percent, 4½ percent, and 4 percent per annum, amounting in the aggregate to $1,500,000,000, which the Secretary of the Treasury was, by the second section of the act, authorized to sell and dispose of at not less than their par value in coin, and "to apply the proceeds thereof to the redemption of any of the bonds of the United States outstanding, and known as five-twenty bonds at their par value," or, the act continues, "he may exchange the same for such five-twenty bonds, par for par."

By the fourth section of this act, it was provided:

That the Secretary of the Treasury is hereby authorized, with any coin of the Treasury of the United States which he may lawfully apply to such purpose, or which may be derived from the sale of any of the bonds, the issue of which is provided for in this act, to pay at par and cancel any six percent bonds of the United States of the kind known as five-twenty bonds which have become, or shall hereafter become, redeemable by the terms of their issue. But the particular bonds so to be paid and cancelled shall in all cases be indicated and specified by class, date, and number, in the order of their numbers and issue, beginning with the first numbered and issued, in public notice to be given by the Secretary of the Treasury, and in three months after the date of such public notice the interest on the bonds so selected and advertised to be paid shall cases.

By an Act passed January 20, 1871, 16 Stat. 399, the foregoing act was amended so as to authorize the issue of five hundred millions of five percent bonds instead of two hundred millions, as limited by the Act of July 14, 1870, but not so as to permit an increase of the aggregate of bonds of all classes thereby authorized.

On March 1, 1871, the nearest date prior to the commencement of operations under the Refunding Act of 1870, the following amounts of six percent five-twenty bonds were outstanding:

- Five-twenties of 1862 . . . . . . . . . . $493,738,350

- Five-twenties of March, 1864. . . . . . . 3,102,600

- Five-twenties of June, 1864 . . . . . . . 102,028,900

- Five-twenties of 1865 . . 182,112,450

- Act March 3, Consols of 1865 . . . . . 264,619,700

- 1865 Consols of 1867 . . . . . 338,832,550

- Consols of 1868 . . . . . 39,663,750

- "The National Loans of the United States," by Bailey, Washington, 1882, p. 94

Of these, large amounts were held abroad by investors in foreign countries, and had been dealt in by bankers in the principal money centers of the world. It was expected and desired by Congress that this should be so, as the Secretary of the Treasury had been expressly authorized by law to dispose of any of the bonds of the United States, "either in the United States or elsewhere." Act March 3, 1865, § 2. And under the Refunding Act of July 14, 1870, as we have already seen, the Secretary of the Treasury established an agency in London for the purpose of delivering the bonds sold under that act and receiving in exchange therefor the outstanding securities of the United States agreed to be received in payment therefor. The object of this great exchange was to reduce the annual interest on the public debt of the United States from six to the lower rates of five, four and one-half, and four percent. To have called in the redeemable debt and paid for it in gold coin, and to have obtained the gold coin for that purpose by sales of the new securities, would have been awkward, circuitous, and impracticable, involving the needless export and import of a mass of the gold coin distributed by the necessities of the world's commerce throughout its markets, the attempt to do which would have produced disturbances of market values, certain to have defeated it. Any transfer of specie in large amounts to meet balances occasioned by these operations would have been almost as serious in its effects, and was therefore by every consideration of public and private interests to be avoided. The difficult practical question was how to avoid it—how to substitute in the markets of the world one loan for the other by an exchange of securities without any serious and disturbing movement of coin. Congress had placed it within the power of the Secretary of the Treasury to accomplish this by authorizing him to receive the five-twenty bonds, to be redeemed in exchange at par for the bonds to be issued at a lower rate of interest. This he was enabled to do by calling in the five-twenty bonds for redemption, by which they were made equal in value as money to par and interest then due and by agreeing to treat and receive them as money in the exchange. This created a demand for the "called bonds" to be used for that purpose, and they were bought from the holders by bankers and agents of the syndicates who had contracted to place the new loans under the act of 1870. This transaction could only have been successfully effected upon the assumption that the call for redemption did not affect the negotiable quality of the bonds, nor impose upon them any disability except the cessation of interest after the maturity of the call, nor deprive them of any other immunity which had previously belonged to them. On the contrary, it must have been within the contemplation of the Treasury Department and of those with whom it was dealing that the "called bonds," until finally absorbed by payments into the Treasury in exchange for new bonds, which constituted the fact of redemption, were equivalent in all legal qualities to money itself or to those usual equivalents of money which circulate, without question as such, like Treasury notes, payable on demand. And this view, we have already seen, the parties were authorized and justified in adopting by the language and purposes of the statutes under which the transactions were accomplished. By this means, an enormous public debt was shifted and converted, so as largely to reduce the burden of its interest; the agents of the government were facilitated in the great work they had undertaken; the individual holders of the securities of the United States, scattered throughout the countries of Europe, received the money due them on the bonds for which they subscribed at their own domiciles, and this series of great financial operations was successfully accomplished without interference with the usual course of the business of the world, without disturbing the fixed distribution of currency which commerce had apportioned to its appropriate markets, and without unsettling the value of property or labor either at home or abroad. These beneficial results were greatly facilitated, if not made feasible, by the unquestioned negotiability of the called bonds, which, when subjected to the right of redemption reserved by their terms, were thereafter considered and treated as the equivalent of money. This could not have been if the principles which protect bona fide purchasers for value, in the due course of trade, without actual notice of a defect in the obligation or title, had not been practically adopted. The practice as found to have existed was in our opinion well warranted by law.

This confidence was invited by the convenience of the government itself, and certainly promoted its interests and advanced its purposes. The practice it engendered on the part of the public dealing in its securities had been expressly sanctioned by formal recognition and approval by the Treasury Department long prior to the negotiation of the war loans, which commenced in 1862. In 1860, Attorney General Black officially advised the Secretary of the Treasury, 9 Opinions 413, that Treasury notes, redeemable after one year from date, interest thereon to cease at the expiration thereafter of sixty days' notice of readiness to pay and redeem the same, were intended to be a continuing security and to pass by delivery, after the period of redemption equally as before, as money or banknotes not liable to any equities between the original or intermediate parties.

It was by force of such a custom declared by Lord Selborne

to be the legitimate, natural, and intended consequence (unless there should be any law to prohibit it) of that representation and engagement which appears on the face of the scrip itself, when construed according to the obvious import of its terms, that in the case of Goodwin Robarts, first in the Exchequer Chamber, L.R. 10 Exch. 337, and afterwards in the House of Lords, 1 App. Cas 476, an instrument, payable to bearer in the bonds of a foreign government, was held to be negotiable by delivery on the ground that after those payments had been made and receipts for them signed, the scrip was as much a symbol of money due and as capable of passing current upon the principle explained in the authorities, with respect to banknotes and exchequer bills as the bonds themselves would have been if they had been actually delivered in exchange for it. The court was therefore of opinion that the title of J.S. Morgan & Co. and of L. Von Hoffman & Co., respectively, to the bonds claimed by them ought to have prevailed against that set up by the Manhattan Savings Institution, and for error in not so holding.

The several judgments of the Court of Claims in these cases were reversed, and the causes are remanded to that court with directions to render judgments in accordance with this opinion.