A mafic mineral or rock is a silicate mineral or igneous rock rich in magnesium and iron. Most mafic minerals are dark in color, and common rock-forming mafic minerals include olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Common mafic rocks include basalt, diabase and gabbro. Mafic rocks often also contain calcium-rich varieties of plagioclase feldspar. Mafic materials can also be described as ferromagnesian.

Hornblende is a complex inosilicate series of minerals. It is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende minerals are common in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

Amphibole is a group of inosilicate minerals, forming prism or needlelike crystals, composed of double chain SiO

4 tetrahedra, linked at the vertices and generally containing ions of iron and/or magnesium in their structures. Its IMA symbol is Amp. Amphiboles can be green, black, colorless, white, yellow, blue, or brown. The International Mineralogical Association currently classifies amphiboles as a mineral supergroup, within which are two groups and several subgroups.

The pyroxenes are a group of important rock-forming inosilicate minerals found in many igneous and metamorphic rocks. Pyroxenes have the general formula XY(Si,Al)2O6, where X represents calcium (Ca), sodium (Na), iron or magnesium (Mg) and more rarely zinc, manganese or lithium, and Y represents ions of smaller size, such as chromium (Cr), aluminium (Al), magnesium (Mg), cobalt (Co), manganese (Mn), scandium (Sc), titanium (Ti), vanadium (V) or even iron. Although aluminium substitutes extensively for silicon in silicates such as feldspars and amphiboles, the substitution occurs only to a limited extent in most pyroxenes. They share a common structure consisting of single chains of silica tetrahedra. Pyroxenes that crystallize in the monoclinic system are known as clinopyroxenes and those that crystallize in the orthorhombic system are known as orthopyroxenes.

Wüstite is a mineral form of mostly iron(II) oxide found with meteorites and native iron. It has a grey colour with a greenish tint in reflected light. Wüstite crystallizes in the isometric-hexoctahedral crystal system in opaque to translucent metallic grains. It has a Mohs hardness of 5 to 5.5 and a specific gravity of 5.88. Wüstite is a typical example of a non-stoichiometric compound.

Nepheline syenite is a holocrystalline plutonic rock that consists largely of nepheline and alkali feldspar. The rocks are mostly pale colored, grey or pink, and in general appearance they are not unlike granites, but dark green varieties are also known. Phonolite is the fine-grained extrusive equivalent.

Peridotite ( PERR-ih-doh-tyte, pə-RID-ə-) is a dense, coarse-grained igneous rock consisting mostly of the silicate minerals olivine and pyroxene. Peridotite is ultramafic, as the rock contains less than 45% silica. It is high in magnesium (Mg2+), reflecting the high proportions of magnesium-rich olivine, with appreciable iron. Peridotite is derived from Earth's mantle, either as solid blocks and fragments, or as crystals accumulated from magmas that formed in the mantle. The compositions of peridotites from these layered igneous complexes vary widely, reflecting the relative proportions of pyroxenes, chromite, plagioclase, and amphibole.

Forsterite (Mg2SiO4; commonly abbreviated as Fo; also known as white olivine) is the magnesium-rich end-member of the olivine solid solution series. It is isomorphous with the iron-rich end-member, fayalite. Forsterite crystallizes in the orthorhombic system (space group Pbnm) with cell parameters a 4.75 Å (0.475 nm), b 10.20 Å (1.020 nm) and c 5.98 Å (0.598 nm).

Ultramafic rocks are igneous and meta-igneous rocks with a very low silica content, generally >18% MgO, high FeO, low potassium, and are composed of usually greater than 90% mafic minerals. The Earth's mantle is composed of ultramafic rocks. Ultrabasic is a more inclusive term that includes igneous rocks with low silica content that may not be extremely enriched in Fe and Mg, such as carbonatites and ultrapotassic igneous rocks.

Lamprophyres are uncommon, small-volume ultrapotassic igneous rocks primarily occurring as dikes, lopoliths, laccoliths, stocks, and small intrusions. They are alkaline silica-undersaturated mafic or ultramafic rocks with high magnesium oxide, >3% potassium oxide, high sodium oxide, and high nickel and chromium.

Komatiite is a type of ultramafic mantle-derived volcanic rock defined as having crystallised from a lava of at least 18 wt% magnesium oxide (MgO). It is classified as a 'picritic rock'. Komatiites have low silicon, potassium and aluminium, and high to extremely high magnesium content. Komatiite was named for its type locality along the Komati River in South Africa, and frequently displays spinifex texture composed of large dendritic plates of olivine and pyroxene.

Ceylonite and pleonaste or pleonast are dingy blue or grey to black varieties of spinel. Ceylonite, named for the island of Ceylon, is a ferroan spinel with Mg:Fe from 3:1 and 1:1, and little or no ferric iron. Pleonaste is named from the Greek for 'abundant,' for its many crystal forms, and is distinguished chemically by low Mg:Fe ratios of approximately 1:3. It is sometimes used as a gemstone.

Cumulate rocks are igneous rocks formed by the accumulation of crystals from a magma either by settling or floating. Cumulate rocks are named according to their texture; cumulate texture is diagnostic of the conditions of formation of this group of igneous rocks. Cumulates can be deposited on top of other older cumulates of different composition and colour, typically giving the cumulate rock a layered or banded appearance.

In inorganic chemistry, mineral hydration is a reaction which adds water to the crystal structure of a mineral, usually creating a new mineral, commonly called a hydrate.

Fractional crystallization, or crystal fractionation, is one of the most important geochemical and physical processes operating within crust and mantle of a rocky planetary body, such as the Earth. It is important in the formation of igneous rocks because it is one of the main processes of magmatic differentiation. Fractional crystallization is also important in the formation of sedimentary evaporite rocks or simply fractional crystallization is the removal of early formed crystals from an Original homogeneous magma so that the crystals are prevented from further reaction with the residual melt.

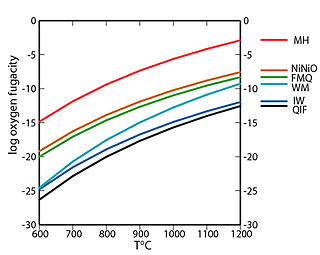

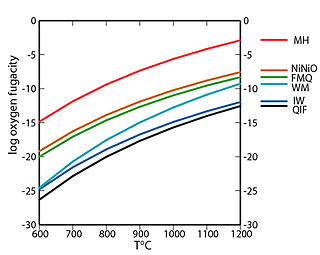

In geology, a redox buffer is an assemblage of minerals or compounds that constrains oxygen fugacity as a function of temperature. Knowledge of the redox conditions (or equivalently, oxygen fugacities) at which a rock forms and evolves can be important for interpreting the rock history. Iron, sulfur, and manganese are three of the relatively abundant elements in the Earth's crust that occur in more than one oxidation state. For instance, iron, the fourth most abundant element in the crust, exists as native iron, ferrous iron (Fe2+), and ferric iron (Fe3+). The redox state of a rock affects the relative proportions of the oxidation states of these elements and hence may determine both the minerals present and their compositions. If a rock contains pure minerals that constitute a redox buffer, then the oxygen fugacity of equilibration is defined by one of the curves in the accompanying fugacity-temperature diagram.

The endmember hornblende tschermakite (☐Ca2(Mg3Al2)(Si6Al2)O22(OH)2) is a calcium rich monoclinic amphibole mineral. It is frequently synthesized along with its ternary solid solution series members tremolite and cummingtonite so that the thermodynamic properties of its assemblage can be applied to solving other solid solution series from a variety of amphibole minerals.

Magmatic water, also known as juvenile water, is an aqueous phase in equilibrium with minerals that have been dissolved by magma deep within the Earth's crust and is released to the atmosphere during a volcanic eruption. It plays a key role in assessing the crystallization of igneous rocks, particularly silicates, as well as the rheology and evolution of magma chambers. Magma is composed of minerals, crystals and volatiles in varying relative natural abundance. Magmatic differentiation varies significantly based on various factors, most notably the presence of water. An abundance of volatiles within magma chambers decreases viscosity and leads to the formation of minerals bearing halogens, including chloride and hydroxide groups. In addition, the relative abundance of volatiles varies within basaltic, andesitic, and rhyolitic magma chambers, leading to some volcanoes being exceedingly more explosive than others. Magmatic water is practically insoluble in silicate melts but has demonstrated the highest solubility within rhyolitic melts. An abundance of magmatic water has been shown to lead to high-grade deformation, altering the amount of δ18O and δ2H within host rocks.

A primary mineral is any mineral formed during the original crystallization of the host igneous primary rock and includes the essential mineral(s) used to classify the rock along with any accessory minerals. In ore deposit geology, hypogene processes occur deep below the Earth's surface, and tend to form deposits of primary minerals, as opposed to supergene processes that occur at or near the surface, and tend to form secondary minerals.

Lamprophyllite is a rare, but widespread mineral Ti-silicate mineral usually found in intrusive agpasitic igneous rocks. Yellow, reddish brown, Vitreous, Pearly.