The Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, is a document signed in 1848 by 68 women and 32 men—100 out of some 300 attendees at the first women's rights convention to be organized by women. Held in Seneca Falls, New York, the convention is now known as the Seneca Falls Convention. The principal author of the Declaration was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who modeled it upon the United States Declaration of Independence. She was a key organizer of the convention along with Lucretia Coffin Mott, and Martha Coffin Wright.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first convention to be called for the sole purpose of discussing women's rights, and was the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. Her demand for women's right to vote generated a controversy at the convention but quickly became a central tenet of the women's movement. She was also active in other social reform activities, especially abolitionism.

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman". Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the town of Seneca Falls, New York, it spanned two days over July 19–20, 1848. Attracting widespread attention, it was soon followed by other women's rights conventions, including the Rochester Women's Rights Convention in Rochester, New York, two weeks later. In 1850 the first in a series of annual National Women's Rights Conventions met in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Martha Coffin Wright was an American feminist, abolitionist, and signatory of the Declaration of Sentiments who was a close friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman.

Mary Grew was an American abolitionist and suffragist whose career spanned nearly the entire 19th century. She was a leader of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. She was one of eight women delegates, all from the United States, who were denied their seats at the London World Anti-Slavery Convention, in 1840. An editor and journalist, she wrote for abolitionist newspapers and chronicled the work of Philadelphia's abolitionists over more than three decades. She was a gifted public orator at a time when it was still noteworthy for women to speak in public. Her obituary summarized her impact: "Her biography would be a history of all reforms in Pennsylvania for fifty years."

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention combined both female and male leadership and attracted a wide base of support including temperance advocates and abolitionists. Speeches were given on the subjects of equal wages, expanded education and career opportunities, women's property rights, marriage reform, and temperance. Chief among the concerns discussed at the convention was the passage of laws that would give women the right to vote.

Lucretia Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. In 1848, she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first public gathering about women's rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, during which the Declaration of Sentiments was written.

The Women's Rights National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park in Seneca Falls and Waterloo, New York, United States. Founded by an act of Congress in 1980 and first opened in 1982, the park was gradually expanded through purchases over the decades that followed. It recognizes the site of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, and the homes of several women's rights activists.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The exclusion of women from the convention gave a great impetus to the women's suffrage movement in the United States.

Mary B. Thistlethwaite Birdsall was an American suffragette, temperance worker, and journalist.

The Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848 met on August 2, 1848 in Rochester, New York. Many of its organizers had participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, two weeks earlier in Seneca Falls, a smaller town not far away. The Rochester convention elected Abigail Bush as its presiding officer, making it the first U.S. public meeting composed of both sexes to be presided by a woman. This controversial step was opposed even by some of the meeting's leading participants. The convention approved the Declaration of Sentiments that had first been introduced at the Seneca Falls Convention, including the controversial call for women's right to vote. It also discussed the rights of working women and took steps that led to the formation of a local organization to support those rights.

The Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 met on April 19–20, 1850 in Salem, Ohio, a center for reform activity. It was the third in a series of women's rights conventions that began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. It was the first of these conventions to be organized on a statewide basis. About five hundred people attended. All of the convention's officers were women. Men were not allowed to vote, sit on the platform or speak during the convention. The convention sent a memorial to the convention that was preparing a new Ohio state constitution, asking it to provide for women's right to vote.

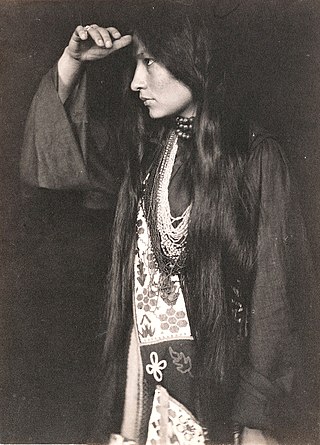

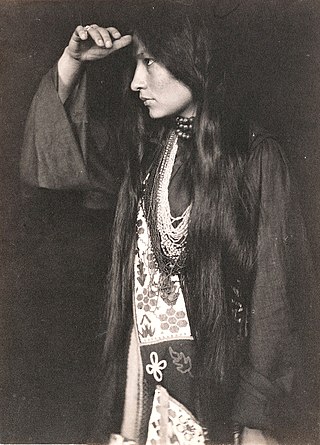

Native American women influenced early women's suffrage activists in the United States. The Iroquois nations, which had an egalitarian society, were visited by early feminists and suffragists, such as Lydia Maria Child, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. These women discussed how Native American women had authority in their own cultures at various feminist conventions and also in the news. Native American women became a symbol for some suffrage activists. However, other white suffragists actively excluded Native American people from the movement. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920, suffragist Zitkala-Sa, commented that Native Americans still had more work to do in order to vote. It was not until 1924 that many Native Americans could vote under the Indian Citizenship Act. In many states, there were additional barriers to Native American voting rights.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Pennsylvania. Activists in the state began working towards women's rights in the early 1850s, when two women's rights conventions discussed women's suffrage. A statewide group, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA), was formed in 1869. Other regional groups were formed throughout the state over the years. Suffragists in Pittsburgh created the "Pittsburgh Plan" in 1911. In 1915, a campaign to influence voters to support women's suffrage on the November 2 referendum took place. Despite these efforts, the referendum failed. On June 24, 1919, Pennsylvania became the seventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Pennsylvania women voted for the first time on November 2, 1920.

The women's suffrage movement in Pennsylvania was an outgrowth of the abolitionist movement in the state. Early women's suffrage advocates in Pennsylvania wanted equal suffrage not only for white women but for all African Americans. The first women's rights convention in the state was organized by Quakers and held in Chester County in 1852. Philadelphia would host the fifth National Women's Rights Convention in 1854. Later years saw suffragists forming a statewide group, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA), and other smaller groups throughout the state. Early efforts moved slowly, but steadily, with suffragists raising awareness and winning endorsements from labor unions.

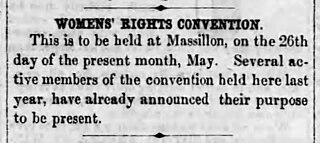

The Ohio Women's Convention at Massillon in 1852 met on May 26, 1852 at Massillon, Ohio. At this meeting participants established the Ohio Women's Rights Association.

The Progressive Friends, also known as the Congregational Friends and the Friends of Human Progress, was a loose-knit group of dissidents who left the Hicksite branch of the Society of Friends (Quakers) in the mid-nineteenth century. The separation was caused by the determination of some Quakers to participate in the social reform movements of the day despite efforts by leading Quaker bodies to dissuade them from mixing with non-Quakers. These reformers were drawn especially to organizations that opposed slavery, but also to those that campaigned for women's rights. The new organizations were structured according to congregationalist polity, a type of organization that gives a large degree of autonomy to local congregations. They were organized on a local and regional basis without the presence of a national organization. They did not see themselves as creators of a new religious sect but of a reform movement that was open to people of all religious beliefs.