The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes relating to religious doctrine or alternative religious beliefs. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Catholic Inquisition along with the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition.

Tommaso Campanella, baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.

The "Letter to The Grand Duchess Christina" is an essay written in 1615 by Galileo Galilei. The intention of this letter was to accommodate Copernicanism with the doctrines of the Catholic Church. Galileo tried to use the ideas of Church Fathers and Doctors to show that any condemnation of Copernicanism would be inappropriate.

The Accademia dei Lincei is one of the oldest and most prestigious European scientific institutions, located at the Palazzo Corsini on the Via della Lungara in Rome, Italy.

Giambattista della Porta, also known as Giovanni Battista Della Porta, was an Italian scholar, polymath and playwright who lived in Naples at the time of the Renaissance, Scientific Revolution and Reformation.

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of 126 arguments concerning the motion of the Earth, and for introducing the current scheme of lunar nomenclature. He is also widely known for discovering the first double star. He argued that the rotation of the Earth should reveal itself because on a rotating Earth, the ground moves at different speeds at different times.

Alexandre Koyré, also anglicized as Alexander Koyre, was a French philosopher of Russian origin who wrote on the history and philosophy of science.

Paolo Frisi was an Italian mathematician and astronomer.

The Galileo affair began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. Galileo was prosecuted for his support of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe.

1634: The Galileo Affair is the fourth book and third novel published in the 1632 series. It is co-written by American authors Eric Flint and Andrew Dennis and was published in 2004. It follows the activities of an embassy party sent from the United States of Europe (Grantville) to Venice, Italy, where the three young Stone brothers become involved with the local Committees of Correspondence and the Inquisition's trial of Galileo Galilei.

Ludovico Geymonat was an Italian mathematician, philosopher and historian of science. As a philosopher, he mainly dealt with philosophy of science, epistemology and Marxist philosophy, in which he gave an original turn to dialectical materialism.

The Assayer was a book published in Rome by Galileo Galilei in October 1623 and is generally considered to be one of the pioneering works of the scientific method, first broaching the idea that the book of nature is to be read with mathematical tools rather than those of scholastic philosophy, as generally held at the time.

Stillman Drake was a Canadian historian of science best known for his work on Galileo Galilei (1569–1642). Drake published over 131 books, articles, and book chapters on Galileo. Including his translations, Drake wrote 16 books on Galileo and contributed to 15 others.

The relationship between science and the Catholic Church is a widely debated subject. Historically, the Catholic Church has been a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation and funding of schools, universities, and hospitals, and many clergy have been active in the sciences. Some historians of science such as Pierre Duhem credit medieval Catholic mathematicians and philosophers such as John Buridan, Nicole Oresme, and Roger Bacon as the founders of modern science. Duhem found "the mechanics and physics, of which modern times are justifiably proud, to proceed by an uninterrupted series of scarcely perceptible improvements from doctrines professed in the heart of the medieval schools." The conflict thesis and other critiques emphasize the historical or contemporary conflict between the Catholic Church and science, citing, in particular, the trial of Galileo as evidence. For its part, the Catholic Church teaches that science and the Christian faith are complementary, as can be seen from the Catechism of the Catholic Church which states in regards to faith and science:

Though faith is above reason, there can never be any real discrepancy between faith and reason. Since the same God who reveals mysteries and infuses faith has bestowed the light of reason on the human mind, God cannot deny himself, nor can truth ever contradict truth. ... Consequently, methodical research in all branches of knowledge provided it is carried out in a truly scientific manner and does not override moral laws, can never conflict with the faith, because the things of the world and the things of faith derive from the same God. The humble and persevering investigator of the secrets of nature is being led, as it were, by the hand of God despite himself, for it is God, the conserver of all things, who made them what they are.

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced. He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence. Galileo has been called the "father" of observational astronomy, modern physics, the scientific method, and modern science.

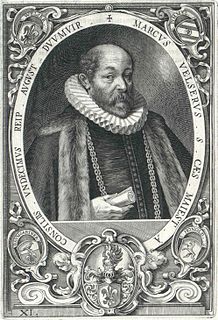

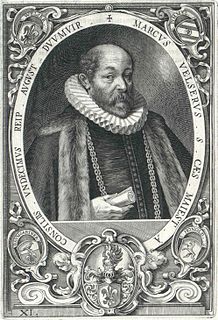

Mark Welser (1558–1614) was a German banker, politician, and astronomer, who engaged in learned correspondence with European intellectuals of his time. Of particular note is his exchange with Galileo Galilei, regarding sunspots.

Giovanni Ciampoli or Giovanni Battista Ciampoli was a priest, poet and humanist. He was closely associated with Galileo Galilei and his disputes with the Catholic Church.

Pietro Corsi is an Italian historian of science.

Tommaso Rinuccini was an Italian noble, diplomat and friend of Galileo Galilei.

Antonella Romano is a French historian of science known for her research on science and the Catholic Church, and in particular on the scientific and mathematical work of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in the Renaissance. She is full professor at the Alexandre Koyré Centre for research in the history of science at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS) in Paris, the former director of the center, and a vice-president of EHESS.