The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclamation forbade all settlements west of a line drawn along the Appalachian Mountains, which was delineated as an Indian Reserve. Exclusion from the vast region of Trans-Appalachia created discontent between Britain and colonial land speculators and potential settlers. The proclamation and access to western lands was one of the first significant areas of dispute between Britain and the colonies and would become a contributing factor leading to the American Revolution. The 1763 proclamation line is situated similar to the Eastern Continental Divide, extending from Georgia to the divide's northern terminus near the middle of the northern border of Pennsylvania, where it intersects the northeasterly St. Lawrence Divide, and extends further through New England.

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War.

The Transylvania Colony, also referred to as the Transylvania Purchase, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in early 1775 by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson, who formed and controlled the Transylvania Company. Henderson and his investors had reached an agreement to purchase a vast tract of Cherokee lands west of the southern and central Appalachian Mountains through the acceptance of the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals with most leading Cherokee chieftains then controlling these lands. In exchange for the land the tribes received goods worth, according to the estimates of some scholars, about 10,000 British pounds. To further complicate matters, this frontier land was also claimed by the Virginia Colony and a southern portion by Province of North Carolina.

Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden, PC was an English lawyer, judge and Whig politician who was first to hold the title of Earl Camden. As a lawyer and judge he was a leading proponent of civil liberties, championing the rights of the jury, and limiting the powers of the State in leading cases such as Entick v Carrington.

A princely state was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to a subsidiary alliance and the suzerainty or paramountcy of the British crown.

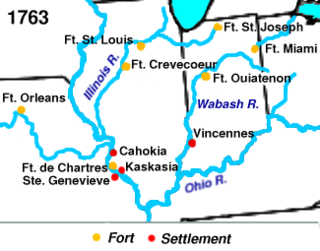

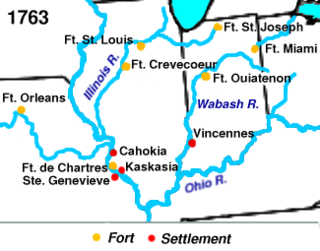

The Illinois-Wabash Company, formally known as the United Illinois and Wabash Land Company, was a company formed in 1779 from the merger of the Illinois Company and the Wabash Company. The two companies had been established in order to purchase land from Native Americans in the Illinois Country, a region of North America acquired by Great Britain in 1763. The Illinois Company purchased two large tracts of land in 1773; the Wabash Company purchased two additional tracts in 1775.

Indian nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds Indian nationality. The two primary pieces of legislation governing these requirements are the Constitution of India and the Citizenship Act, 1955.

The legal system of Singapore is based on the English common law system. Major areas of law – particularly administrative law, contract law, equity and trust law, property law and tort law – are largely judge-made, though certain aspects have now been modified to some extent by statutes. However, other areas of law, such as criminal law, company law and family law, are almost completely statutory in nature.

The Indian Independence Act 1947 is an action of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 July 1947 and thus modern-day India and Pakistan, comprising west and east regions, came into being on 15 August.

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another, they existed between 1612 and 1947, conventionally divided into three historical periods:

Events from the year 1757 in Great Britain.

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, the content of aboriginal title, the methods of extinguishing aboriginal title, and the availability of compensation in the case of extinguishment vary significantly by jurisdiction. Nearly all jurisdictions are in agreement that aboriginal title is inalienable, and that it may be held either individually or collectively.

The Singranatore family is the consanguineous name given to a noble family in Rajshahi of landed aristocracy in erstwhile East Bengal and West Bengal that were prominent in the nineteenth century till the fall of the monarchy in India by Royal Assent in 1947 and subsequently abolished by the newly formed democratic Government of East Pakistan in 1950 by the State Acquisition Act.

The Haldimand Proclamation was a decree that granted land to the Mohawk who had served on the British side during the American Revolution. The decree was issued by the Governor of the Province of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand, on October 25, 1784, three days after the Treaty of Fort Stanwix was signed between others of the Six Nations and the American government. The granted land had to be purchased from the Mississaugas of the Credit whose traditional territory spans much of modern-day Southwestern Ontario. On May 22, 1784 Col. John Butler was sent to negotiate the sale of approximately 3,000,000 acres of land located between Lakes Huron, Ontario, and Erie for £1180.00 from the Mississaugas of the Credit. Of the land ceded, some 550,000 acres were granted to the Mohawk nation in the Haldimand Proclamation. The sale by the Mississaugas of the Credit is also referred to as the "Between the Lakes Treaty."

The regiments of Bengal Native Infantry, alongside the regiments of Bengal European Infantry, were the regular infantry components of the East India Company's Bengal Army from the raising of the first Native battalion in 1757 to the passing into law of the Government of India Act 1858. At this latter point control of the East India Company's Bengal Presidency passed to the British Government. The first locally recruited battalion was raised by the East India Company in 1757 and by the start of 1857 there were 74 regiments of Bengal Native Infantry in the Bengal Army. Following the Mutiny the Presidency armies came under the direct control of the United Kingdom Government and there was a widespread reorganisation of the Bengal Army that saw the Bengal Native Infantry regiments reduced to 45.

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States the term treaty rights specifically refers to rights for indigenous peoples enumerated in treaties with settler societies that arose from European colonization.

Land is owned in Canada by governments, Indigenous groups, corporations, and individuals. Canada is the second-largest country in the world by area; at 9,093,507 km2 or 3,511,085 mi2 of land. It occupies more than 6% of the Earth's surface.

Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy, 162 U.S. 283 (1896), was the first litigation of aboriginal title in the United States by a tribal plaintiff in the Supreme Court of the United States since Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831). It was the first such litigation by an indigenous plaintiff since Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857) and its companion case of New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble (1858). The New York courts held that the 1788 Phelps and Gorham Purchase did not violate the Nonintercourse Act, one of the provisions of which prohibits purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government, and that the Seneca Nation of New York was barred by the state statute of limitations from challenging the transfer of title. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the merits of lower court ruling because of the adequate and independent state grounds doctrine.

The Marshall Court (1801–1835) issued some of the earliest and most influential opinions by the Supreme Court of the United States on the status of aboriginal title in the United States, several of them written by Chief Justice John Marshall himself. However, without exception, the remarks of the Court on aboriginal title during this period are dicta. Only one indigenous litigant ever appeared before the Marshall Court, and there, Marshall dismissed the case for lack of original jurisdiction.

Tort law in India is primarily governed by judicial precedent as in other common law jurisdictions, supplemented by statutes governing damages, civil procedure, and codifying common law torts. As in other common law jurisdictions, a tort is breach of a non-contractual duty which has caused damage to the plaintiff giving rise to a civil cause of action and for which remedy is available. If a remedy does not exist, a tort has not been committed since the rationale of tort law is to provide a remedy to the person who has been wronged.