Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In the United States, it is regarded as a standalone conflict under this name. Elsewhere it is usually viewed as the American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession. It is also known as the Third Indian War. In France it was known as the Second Intercolonial War.

Acadia was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early 18th centuries, Norridgewock on the Kennebec River and Castine at the end of the Penobscot River were the southernmost settlements of Acadia. The French government specified land bordering the Atlantic coast, roughly between the 40th and 46th parallels. It was eventually divided into British colonies. The population of Acadia included the various indigenous First Nations that comprised the Wabanaki Confederacy, the Acadian people and other French settlers.

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians, was the forced removal, by the British, of inhabitants of parts of a Canadian-American region historically known as Acadia, between 1755 and 1764. The area included the present-day Canadian Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, and the present-day U.S. state of Maine. The Expulsion, which caused the deaths of thousands of people, occurred during the French and Indian War and was part of the British military campaign against New France.

The Isthmus of Chignecto is an isthmus bordering the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia that connects the Nova Scotia peninsula with North America.

Dummer's War (1722–1725) was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the Wabanaki Confederacy, who were allied with New France. The eastern theater of the war was located primarily along the border between New England and Acadia in Maine, as well as in Nova Scotia; the western theater was located in northern Massachusetts and Vermont at the border between Canada and New England. During this time, Maine and Vermont were part of Massachusetts.

The Acadians are the descendants of 17th and 18th century French settlers in parts of Acadia in the northeastern region of North America comprising what is now the Canadian Maritime Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, the Gaspé peninsula in eastern Québec, and the Kennebec River in southern Maine. The settlers whose descendants became Acadians primarily came from the southwestern and southern regions of France, historically known as Occitania, while some Acadians are claimed to be descended from the Indigenous peoples of the region. Today, due to assimilation, some Acadians may share other ethnic ancestries as well.

The siege of Port Royal in 1707 included two separate attempts by English colonists from New England to conquer Acadia by capturing its capital Port Royal during Queen Anne's War. Both attempts were made by colonial militia, and were led by men inexperienced in siege warfare. Led by Acadian Governor Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, the French troops at Port Royal easily withstood both attempts, assisted by irregular Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy outside the fort.

The siege of Port Royal, also known as the Conquest of Acadia, was a military siege conducted by British regular and provincial forces under the command of Francis Nicholson against a French Acadian garrison and the Wabanaki Confederacy under the command of Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, at the Acadian capital, Port Royal. The successful British siege marked the beginning of permanent British control over the peninsular portion of Acadia, which they renamed Nova Scotia, and it was the first time the British took and held a French colonial possession. After the French surrender, the British occupied the fort in the capital with all the pomp and ceremony of having captured one of the great fortresses of Europe, and renamed it Annapolis Royal.

The siege of Grand Pré happened during Father Le Loutre's War and was fought between the British and the Wabanaki Confederacy and Acadian militia. The siege happened at Fort Vieux Logis, Grand-Pré. The native and Acadia militia laid siege to Fort Vieux Logis for a week in November 1749. One historian states that the intent of the siege was to help facilitate the Acadian Exodus from the region.

The Raid on Chignecto occurred during King William's War when New England forces from Boston attacked the Isthmus of Chignecto, Acadia in present-day Nova Scotia. The raid was in retaliation for the French and Indian Siege of Pemaquid (1696) at present day Bristol, Maine. In the English Province of Massachusetts Bay. Colonel Benjamin Church was the leader of the New England force of 400 men. The raid lasted nine days, between September 20–29, 1696, and formed part of a larger expedition by Church against a number of other Acadian communities.

The Battle of Chedabucto occurred against Fort St. Louis in Chedabucto on June 3, 1690 during King William's War (1689–97). The battle was part of Sir William Phips and New England's military campaign against Acadia. New England sent an overwhelming force to conquer Acadia by capturing the capital Port Royal, Chedabucto, and attacking other villages. The aftermath of these battles was unlike any of the previous military campaigns against Acadia. The violence of the attacks alienated many of the Acadians from the New Englanders, broke their trust, and made it difficult for them to deal amicably with the English-speakers.

The Battle at Chignecto happened during Father Le Loutre's War when Charles Lawrence, in command of the 45th Regiment of Foot and the 47th Regiment, John Gorham in command of the Rangers and Captain John Rous in command of the navy, fought against the French monarchists at Chignecto. This battle was the first attempt by the British to occupy the head of the Bay of Fundy since the disastrous Battle of Grand Pré three years earlier. They fought against a militia made up of Mi'kmaq and Acadians led by Jean-Louis Le Loutre and Joseph Broussard (Beausoliel). The battle happened at Isthmus of Chignecto, Nova Scotia on 3 September 1750.

The siege of Fort Nashwaak occurred during King William's War when New England forces from Boston attacked the capital of Acadia, Fort Nashwaak, at present-day Fredericton, New Brunswick. The siege was in retaliation for the French and Indian Siege of Pemaquid (1696) at present day Bristol, Maine. In the English Province of Massachusetts Bay. Colonel John Hathorne and Major Benjamin Church were the leaders of the New England force of 400 men. The siege lasted two days, between October 18–20, 1696, and formed part of a larger expedition by Church against a number of other Acadian communities.

Nova Scotia is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Maritime Provinces and the northern part of Maine, all of which were at one time part of Nova Scotia. In 1763, Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the colony was primarily made up of Catholic Acadians, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq. During the last 75 years of this time period, there were six colonial wars that took place in Nova Scotia. After agreeing to several peace treaties, the long period of warfare ended with the Halifax Treaties (1761) and two years later, when the British defeated the French in North America (1763). During those wars, the Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from the region fought to protect the border of Acadia from New England. They fought the war on two fronts: the southern border of Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine, and in Nova Scotia, which involved preventing New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal and establishing themselves at Canso.

The Northeast Coast campaign was the first major campaign by the French of Queen Anne's War in New England. Alexandre Leneuf de La Vallière de Beaubassin led 500 troops made up of French colonial forces and the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia. They attacked English settlements on the coast of present-day Maine between Wells and Casco Bay, burning more than 15 leagues of New England country and killing or capturing more than 150 people. The English colonists protected some of their settlements, but a number of others were destroyed and abandoned. Historian Samuel Drake reported that, "Maine had nearly received her death-blow" as a result of the campaign.

Port Royal (1605–1713) was a historic settlement based around the upper Annapolis Basin in Nova Scotia, Canada, and the predecessor of the modern town of Annapolis Royal. It was the first successful attempt by Europeans to establish a permanent settlement in what is today known as Canada. Port Royal was a key step in the development of New France and was the first permanent base of operations of the explorer Samuel de Champlain who would later found Quebec in 1608 and the farmer Louis Hébert, who would resettle at Quebec in 1617. For most of its existence, it was the capital of the New France colony of Acadia.

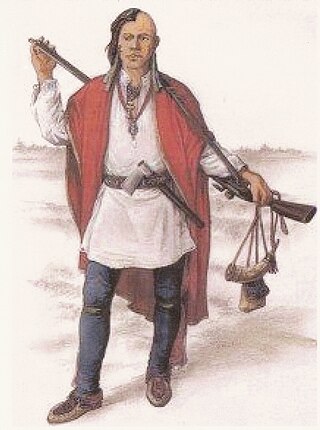

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who participated in wars against the English independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants. After some engagements against the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties. After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy and French royal forces. A number of Acadians provided military intelligence, sanctuary, and logistical support to the various resistance movements against British rule in Acadia, while other Acadians remained neutral in the contest between the Franco–Wabanaki Confederacy forces and the British. The Acadian militias managed to maintain an effective resistance movement for more than 75 years and through six wars before their eventual demise. According to Acadian historian Maurice Basque, the story of Evangeline continues to influence historic accounts of the expulsion, emphasising Acadians who remained neutral and de-emphasising those who joined resistance movements. While Acadian militias were briefly active during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century. After confederation, Acadians eventually joined the Canadian War efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Joseph Broussard and Joseph-Nicolas Gautier.

Fort St. Louis was a French fort built in Chedabucto, Acadia. The British attacked in 1720 as they built Fort William Augustus at Canso.

The Battle of Falmouth was fought at Falmouth, Maine when the Canadiens and Wabanaki Confederacy attacked the English New Casco Fort. The battle was part of the Northeast Coast Campaign (1703) during Queen Anne's War.