Sonohyan-utaki(園比屋武御嶽, Okinawan: Sunuhyan-utaki) is a sacred grove of trees and plants ( utaki ) of the traditional indigenous Ryukyuan religion. It is located on the grounds of Shuri Castle in Naha, Okinawa, a few paces away from the Shureimon castle gate. The utaki, or more specifically its stone gate(石門ishimon), [1] is one of a number of sites which together comprise the UNESCO World Heritage Site officially described as Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu , and has been designated an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese national government. [2]

The Okinawan language, or Central Okinawan, is a Northern Ryukyuan language spoken primarily in the southern half of the island of Okinawa, as well as in the surrounding islands of Kerama, Kumejima, Tonaki, Aguni, and a number of smaller peripheral islands. Central Okinawan distinguishes itself from the speech of Northern Okinawa, which is classified independently as the Kunigami language. Both languages have been designated as endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger since its launch in February 2009.

Utaki (御嶽) is an Okinawan term for a sacred place, often a grove, cave, or mountain. They are central to the Ryukyuan religion and the former noro priestess system. Although the term utaki is used throughout the Ryukyu Islands, the terms suku and on are heard in the Miyako and Yaeyama regions respectively. Utaki are usually located on the outskirts of villages and are places for the veneration of gods and ancestors. Most gusuku have places of worship, and it is theorized that the origins of both gusuku and utaki are closely related.

The Ryukyuan religion (琉球信仰), Ryukyu Shintō (琉球神道), Nirai Kanai Shinkō (ニライカナイ信仰), or Utaki Shinkō (御嶽信仰) is the indigenous belief system of the Ryukyu Islands. While specific legends and traditions may vary slightly from place to place and island to island, the Ryukyuan religion is generally characterized by ancestor worship and the respecting of relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods and spirits of the natural world. Some of its beliefs, such as those concerning genius loci spirits and many other beings classified between gods and humans, are indicative of its ancient animistic roots, as is its concern with mabui(まぶい), or life essence.

While the gates were once opened only for the king, today they are always closed, and so the gates have in a way become a sacred space themselves, representative of the actual sacred space behind them. Many travellers and locals come to pray at the gates. [1]

The stone gate was first built in 1519, during the reign of Ryukyuan king Shō Shin, though the space had been recognized as a sacred utaki prior to that. Whenever the king left the castle on a journey, he would first stop at Sonohyan-utaki to pray for safe travels. [1] The site also played an important role in the initiation of the High Priestess(聞得大君 kikoe-ōgimi ) of the native religion.

Shō Shin was a king of the Ryukyu Kingdom, the third of the line of the Second Shō Dynasty. Shō Shin's long reign has been described as "the Great Days of Chūzan", a period of great peace and relative prosperity. He was the son of Shō En, the founder of the dynasty, by Yosoidon, Shō En's second wife, often referred to as the queen mother. He succeeded his uncle, Shō Sen'i, who was forced to abdicate in his favor.

Kikoe-ōgimi was the highest ranking noro priestess of the Ryukyuan religion during the period of the Ryukyu Kingdom.

The gate is said to be a prime example of traditional Okinawan architecture, and shows many signs of Chinese influence, along with a Japanese-influenced gable in the karahafu style. [1] It was severely damaged in the 1945 battle of Okinawa, but was restored in 1957, and officially designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000, along with a number of other sites across Okinawa Island. The utaki, i.e. the sacred grove itself, was once much larger than it is today, an elementary school and other buildings having encroached upon the space.

Chinese architecture demonstrates an architectural style that developed over millennia in China, before spreading out to influence architecture all throughout East Asia. Since the solidification of the style in the early imperial period, the structural principles of Chinese architecture have remained largely unchanged, the main changes being only the decorative details. Starting with the Tang Dynasty, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Korea, Japan and Vietnam, and a varying amount of influence on the architectural styles of Northeast and Southeast Asia including Mongolia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Indonesia. Chinese architecture is typified by various features; such as, bilateral symmetry, use of enclosed open spaces, the incorporation of ideas related to feng shui such as directional hierarchies, a horizontal emphasis, and the allusion to various cosmological, mythological, or other symbolism. Chinese architecture traditionally classifies structures according to type, ranging from pagodas to palaces. In part because of an emphasis on the use of wood, a relatively perishable material, and due to a de-emphasis on major monumental structures built of less-organic but more durable materials, much of the historical knowledge of Chinese architecture derives from surviving miniature models in ceramic and published planning diagrams and specifications. Some of the architecture of China shows the influence of other types or styles from outside of China, such as the influences on mosque structures originating in the Middle East. Although displaying certain unifying aspects, rather than being completely homogeneous, Chinese architecture has many types of variation based on status or affiliation, such as dependence on whether the structures were constructed for emperors, commoners, or used for religious purposes. Other variations in Chinese architecture are shown in the varying styles associated with different geographic regions and in ethnic architectural design.

The architecture of China is as old as Chinese civilization. From every source of information—literary, graphic, exemplary—there is strong evidence testifying to the fact that the Chinese have always enjoyed an indigenous system of construction that has retained its principal characteristics from prehistoric times to the present day. Over the vast area from Chinese Turkistan to Japan, from Manchuria to the northern half of French Indochina, the same system of construction is prevalent; and this was the area of Chinese cultural influence. That this system of construction could perpetuate itself for more than four thousand years over such a vast territory and still remain a living architecture, retaining its principal characteristics in spite of repeated foreign invasions—military, intellectual, and spiritual—is a phenomenon comparable only to the continuity of the civilization of which it is an integral part.

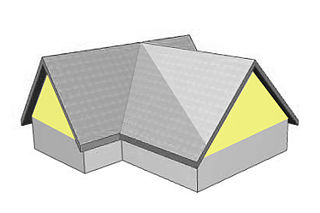

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesthetic concerns. A gable wall or gable end more commonly refers to the entire wall, including the gable and the wall below it.

The karahafu (kara-hafu) (唐破風) is a type of gable with a style peculiar to Japan. The characteristic shape is the undulating curve at the top. This gable is common in traditional architecture, including Japanese castles, Buddhist temples, and Shinto shrines. Roofing materials such as tile and bark may be used as coverings. The face beneath the gable may be flush with the wall below, or it may terminate on a lower roof.