Ahmose I was a pharaoh and founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. He was a member of the Theban royal house, the son of pharaoh Seqenenre Tao and brother of the last pharaoh of the Seventeenth Dynasty, Kamose. During the reign of his father or grandfather, Thebes rebelled against the Hyksos, the rulers of Lower Egypt. When he was seven years old, his father was killed, and he was about ten when his brother died of unknown causes after reigning only three years. Ahmose I assumed the throne after the death of his brother, and upon coronation became known as Nebpehtyre, nb-pḥtj-rꜥ "The Lord of Strength is Ra".

Hyksos is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt. The seat of power of these kings was the city of Avaris in the Nile Delta, from where they ruled over Lower Egypt and Middle Egypt up to Cusae.

Manfred Bietak is an Austrian archaeologist. He is professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Vienna, working as the principal investigator for an ERC Advanced Grant Project "The Hyksos Enigma" and editor-in-chief of the journal Ägypten und Levante and of four series of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental and European Archaeology (2016–2020).

Avaris was the Hyksos capital of Egypt located at the modern site of Tell el-Dab'a in the northeastern region of the Nile Delta. As the main course of the Nile migrated eastward, its position at the hub of Egypt's delta emporia made it a major capital suitable for trade. It was occupied from about the 18th century BC until its capture by Ahmose I.

Sharuhen was an ancient town in the Negev Desert or perhaps in Gaza. Following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt in the second half of the 16th century BCE, they fled to Sharuhen and fortified it. The armies of Pharaoh Ahmose I seized and razed the town after a three-year siege.

Apepi, Apophis ; regnal names Nebkhepeshre, Aaqenenre and Aauserre) was a Hyksos ruler of Lower Egypt during the Fifteenth Dynasty and the end of the Second Intermediate Period. According to the Turin Canon of Kings, he reigned over the northern portion of Egypt for forty years during the early half of the 16th century BCE. Although officially only in control of the Lower Kingdom, Apepi in practice dominated the majority of Egypt during the early portion of his reign. He outlived his southern rival, Kamose, but not Ahmose I.

Pi-Ramesses was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a summer palace under Seti I, and may have been founded by Ramesses I while he served under Horemheb.

Labib Habachi was a Coptic Egyptian egyptologist.

Seuserenre Khyan (also Khayan or Khian was a Hyksos king of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling over Lower Egypt in the second half of the 17th century BCE. His royal name Seuserenre translates as "The one whom Re has caused to be strong." Khyan bears the titles of an Egyptian king, but also the title ruler of the foreign land. The later title is the typical designation of the Hyksos rulers.

Sakir-Har was a Hyksos king of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling over some part of Lower Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, possibly in the early 16th century BC.

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as Minoan paintings, statuettes, vessels for rituals and seals and rings. Minoan religion is considered to have been closely related to Near Eastern ancient religions, and its central deity is generally agreed to have been a goddess, although a number of deities are now generally thought to have been worshipped. Prominent Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and the horns of consecration, the labrys double-headed axe, and possibly the serpent.

Nehesy Aasehre (Nehesi) was a ruler of Lower Egypt during the fragmented Second Intermediate Period. He is placed by most scholars into the early 14th Dynasty, as either the second or the sixth pharaoh of this dynasty. As such he is considered to have reigned for a short time c. 1705 BC and would have ruled from Avaris over the eastern Nile Delta. Recent evidence makes it possible that a second person with this name, a son of a Hyksos king, lived at a slightly later time during the late 15th Dynasty c. 1580 BC. It is possible that most of the artefacts attributed to the king Nehesy mentioned in the Turin canon, in fact belong to this Hyksos prince.

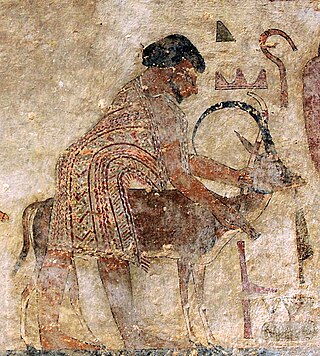

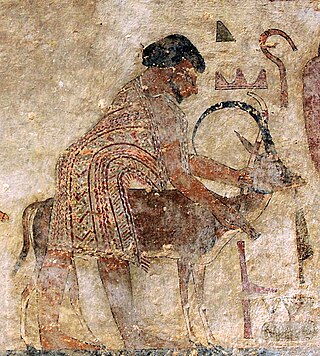

The Minoan wall paintings at Tell el-Dab'a are of particular interest to Egyptologists and archaeologists. They are of Minoan style, content, and technology, but there is uncertainty over the ethnic identity of the artists. The paintings depict images of bull-leaping, bull-grappling, griffins, and hunts. They were discovered by a team of archaeologists led by Manfred Bietak, in the palace district of the Thutmosid period at Tell el-Dab'a. The frescoes date to the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, most likely during the reigns of either the pharaohs Hatshepsut or Thutmose III, after being previously considered to belong to the late Second Intermediate Period. The paintings indicate an involvement of Egypt in international relations and cultural exchanges with the Eastern Mediterranean either through marriage or exchange of gifts.

Hotepibre Qemau Siharnedjheritef was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 13th Dynasty during the Second Intermediate Period.

Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware or Tell el-Yahudiya ware is a distinctive ceramic ware of the late Middle Bronze Age/Second Intermediate Period. The ware takes its name from its type site at Tell el-Yahudiyeh in the eastern Nile Delta of ancient Egypt, and is also found in a large number of Levantine and Cypriot sites. It was first recognised as a distinctive ware by Sir Flinders Petrie during his excavation of the type site.

Tel Haror or Tell Abu Hureyra, also known as Tel Heror, is an archaeological site in the western Negev Desert, Israel, northwest of Beersheba, about 20 km east of the Mediterranean Sea, situated on the north bank of Wadi Gerar, a wadi known in Arabic as Wadi esh-Sheri'a. During the Middle Bronze Age II it was one of the largest urban centres in the area, occupying about 40 acres. The city contains substantial remains of Middle Bronze Age II through to Persian-period settlement strata.

The ancient Egyptian Temple of Ezbet Rushdi was discovered near the modern village of Ezbet Rushdi el-Saghira – itself just north of Tell el-Dab'a, the ancient Avaris – and dates to the Twelfth Dynasty. It was first excavated from 1951 by Shehata Adam who was working for the Egyptian Antiquities Service. The temple was again excavated in 1996 by an Austrian mission under Manfred Bietak.

Yanassi was a Hyksos prince, and possibly king, of the Fifteenth Dynasty. He was the eldest son of the pharaoh Khyan, and possibly the crown prince, designated to be Khyan's successor. He may have succeeded his father, thereby giving rise to the mention of a king "Iannas" in Manetho's Aegyptiaca, who, improbably, was said to have ruled after the pharaoh Apophis.

Many naval bases were located in and around Egypt in the ancient times of this world. The particular naval base of Peru-nefer was one of the bases established in the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt. Perunefer is, according to Manfred Bietak, identified with Tell el-Daba or Ezbet Helmy. Support for this theory comes from excavations and digs that were conducted around the area the naval base was believed to be.

Abattoir Hill, pronounced in Hebrew as Giv'at Bet Hamitbahayim, is an archaeological site in Tel Aviv, Israel, located near the southern bank of the Yarkon River. The site is a natural hill made of Kurkar, a local type of sandstone. In 1930 ancient burials and tools were discovered upon the construction of an abattoir on top of the hill, hence its name. Between 1950 and 1953, Israeli archaeologist Jacob Kaplan studied the site, ahead of the construction of new residential units and streets on it. He discovered the remains of burials and small settlements spanning from the Chalcolithic period to the Persian period. In 1965 and 1970 Kaplan conducted two more excavations next to the slaughterhouse and discovered settlement remains from the Bronze Age and the Persian period. In February 1992 a salvage excavation was conducted by Yossi Levy after antiquities were damaged by development works. Two burial tombs dated between the Persian period and the Early Arab period were discovered. In June 1998 another salvage excavation was conducted by Kamil Sari after ancient remains were damaged by work of the Electric Corporation. Two kilns were unearthed, similar to two found by Kaplan.