Osiris is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail. He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother Set cut him up into pieces after killing him, Osiris' wife Isis found all the pieces and wrapped his body up, enabling him to return to life. Osiris was widely worshipped until the decline of ancient Egyptian religion during the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

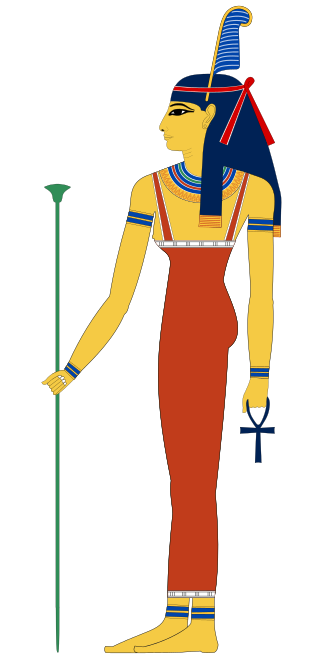

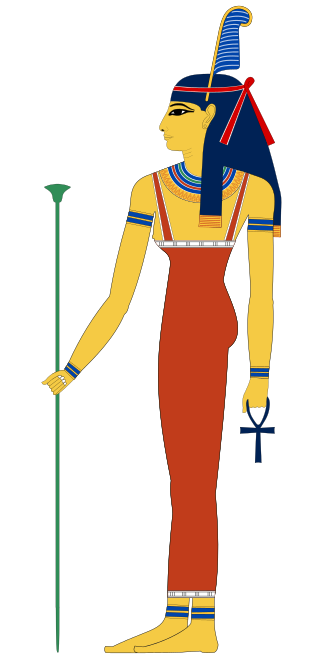

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain brother and husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom, as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

Horus, also known as Heru, Har, Her or Hor in Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun and the sky. He was worshipped from at least the late prehistoric Egypt until the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Roman Egypt. Different forms of Horus are recorded in history, and these are treated as distinct gods by Egyptologists. These various forms may be different manifestations of the same multi-layered deity in which certain attributes or syncretic relationships are emphasized, not necessarily in opposition but complementary to one another, consistent with how the Ancient Egyptians viewed the multiple facets of reality. He was most often depicted as a falcon, most likely a lanner falcon or peregrine falcon, or as a man with a falcon head.

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris's murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris's wife Isis restores her husband's body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set's rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus's triumph, which restores maat to Egypt after Set's unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris's resurrection.

Set is a god of deserts, storms, disorder, violence, and foreigners in ancient Egyptian religion. In Ancient Greek, the god's name is given as Sēth (Σήθ). Set had a positive role where he accompanies Ra on his barque to repel Apep, the serpent of Chaos. Set had a vital role as a reconciled combatant. He was lord of the Red Land (desert), where he was the balance to Horus' role as lord of the Black Land.

Shu was one of the primordial Egyptian gods, spouse and brother to the goddess Tefnut, and one of the nine deities of the Ennead of the Heliopolis cosmogony. He was the god of peace, lions, air, and wind.

Tefnut is a deity of moisture, moist air, dew and rain in Ancient Egyptian religion. She is the sister and consort of the air god Shu and the mother of Geb and Nut.

Nephthys or Nebet-Het in ancient Egyptian was a goddess in ancient Egyptian religion. A member of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis in Egyptian mythology, she was a daughter of Nut and Geb. Nephthys was typically paired with her sister Isis in funerary rites because of their role as protectors of the mummy and the god Osiris and as the sister-wife of Set.

The Ennead or Great Ennead was a group of nine deities in Egyptian mythology worshipped at Heliopolis: the sun god Atum; his children Shu and Tefnut; their children Geb and Nut; and their children Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. The Ennead sometimes includes Horus the Elder, an ancient form of the falcon god, not the son of Osiris and Isis.

Ammit was an ancient Egyptian goddess with the forequarters of a lion, the hindquarters of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile—the three largest "man-eating" animals known to ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egyptian religion, Ammit played an important role during the funerary ritual, the Judgment of the Dead.

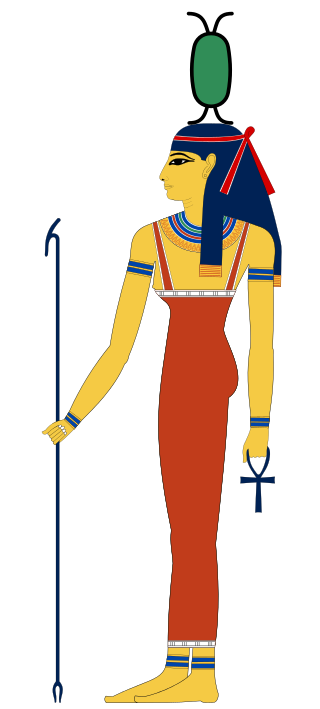

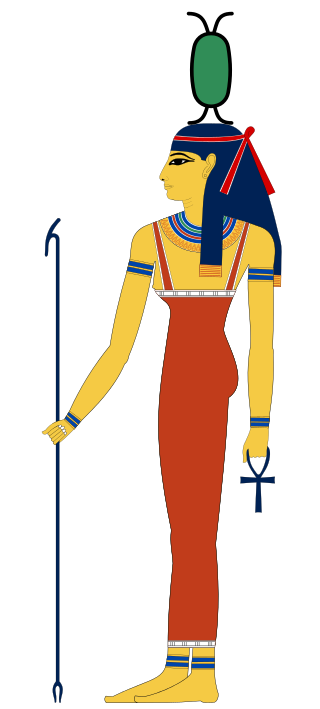

Maat or Maʽat comprised the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet, meaning injustice, chaos, violence or to do evil.

Neith was an early ancient Egyptian deity. She was said to be the first and the prime creator, who created the universe and all it contains, and that she governs how it functions. She was the goddess of the cosmos, fate, wisdom, water, rivers, mothers, childbirth, hunting, weaving, and war.

Hathor was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god Ra, both of whom were connected with kingship, and thus she was the symbolic mother of their earthly representatives, the pharaohs. She was one of several goddesses who acted as the Eye of Ra, Ra's feminine counterpart, and in this form she had a vengeful aspect that protected him from his enemies. Her beneficent side represented music, dance, joy, love, sexuality, and maternal care, and she acted as the consort of several male deities and the mother of their sons. These two aspects of the goddess exemplified the Egyptian conception of femininity. Hathor crossed boundaries between worlds, helping deceased souls in the transition to the afterlife.

This is an index of Egyptian mythology articles.

The royal titulary or royal protocol is the standard naming convention taken by the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. It symbolised worldly power and holy might, also acting as a sort of mission statement for the duration of a monarch's reign.

Instructions of Amenemhat is a short ancient Egyptian poem of the sebayt genre written during the early Middle Kingdom. The poem takes the form of an intensely dramatic monologue delivered by the ghost of the murdered 12th Dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat I to his son Senusret I. It describes the conspiracy that killed Amenemhat, and enjoins his son to trust no-one. The poem forms a kind of apologia of the deeds of the old king's reign. It ends with an exhortation to Senusret to ascend the throne and rule wisely in Amenemhat's stead.

Ra or Re was the ancient Egyptian deity of the Sun. By the Fifth Dynasty, in the 25th and 24th centuries BC, he had become one of the most important gods in ancient Egyptian religion, identified primarily with the noon-day sun. Ra ruled in all parts of the created world: the sky, the Earth, and the underworld. He was believed to have ruled as the first pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. He was the god of the sun, order, kings and the sky.

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments.

Heqet, sometimes spelled Heket, is an Egyptian goddess of fertility, identified with Hathor, represented in the form of a frog. To the Egyptians, the frog was an ancient symbol of fertility, related to the annual flooding of the Nile. Heqet was originally the female counterpart of Khnum, or the wife of Khnum by whom she became the mother of Her-ur. It has been proposed that her name is the origin of the name of Hecate, the Greek goddess of witchcraft.

"The Contendings of Horus and Seth" is a mythological story from the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt found in the first sixteen pages of the Chester Beatty Papyri and deals with the battles between Horus and Seth to determine who will succeed Osiris as king.