A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-invested in the business. The current year profit as well as the retained earnings of previous years are available for distribution; a corporation is usually prohibited from paying a dividend out of its capital. Distribution to shareholders may be in cash or, if the corporation has a dividend reinvestment plan, the amount can be paid by the issue of further shares or by share repurchase. In some cases, the distribution may be of assets.

In finance, a bond is a type of security under which the issuer (debtor) owes the holder (creditor) a debt, and is obliged – depending on the terms – to provide cash flow to the creditor. The timing and the amount of cash flow provided varies, depending on the economic value that is emphasized upon, thus giving rise to different types of bonds. The interest is usually payable at fixed intervals: semiannual, annual, and less often at other periods. Thus, a bond is a form of loan or IOU. Bonds provide the borrower with external funds to finance long-term investments or, in the case of government bonds, to finance current expenditure.

In accounting, book value is the value of an asset according to its balance sheet account balance. For assets, the value is based on the original cost of the asset less any depreciation, amortization or impairment costs made against the asset. Traditionally, a company's book value is its total assets minus intangible assets and liabilities. However, in practice, depending on the source of the calculation, book value may variably include goodwill, intangible assets, or both. The value inherent in its workforce, part of the intellectual capital of a company, is always ignored. When intangible assets and goodwill are explicitly excluded, the metric is often specified to be tangible book value.

Preferred stock is a component of share capital that may have any combination of features not possessed by common stock, including properties of both an equity and a debt instrument, and is generally considered a hybrid instrument. Preferred stocks are senior to common stock but subordinate to bonds in terms of claim and may have priority over common stock in the payment of dividends and upon liquidation. Terms of the preferred stock are described in the issuing company's articles of association or articles of incorporation.

A sinking fund is a fund established by an economic entity by setting aside revenue over a period of time to fund a future capital expense, or repayment of a long-term debt.

In the United Kingdom, taxation may involve payments to at least three different levels of government: central government, devolved governments and local government. Central government revenues come primarily from income tax, National Insurance contributions, value added tax, corporation tax and fuel duty. Local government revenues come primarily from grants from central government funds, business rates in England, Council Tax and increasingly from fees and charges such as those for on-street parking. In the fiscal year 2014–15, total government revenue was forecast to be £648 billion, or 37.7 per cent of GDP, with net taxes and National Insurance contributions standing at £606 billion.

The retained earnings of a corporation is the accumulated net income of the corporation that is retained by the corporation at a particular point of time, such as at the end of the reporting period. At the end of that period, the net income at that point is transferred from the Profit and Loss Account to the retained earnings account. If the balance of the retained earnings account is negative it may be called accumulated losses, retained losses or accumulated deficit, or similar terminology.

A corporate tax, also called corporation tax or company tax, is a type of direct tax levied on the income or capital of corporations and other similar legal entities. The tax is usually imposed at the national level, but it may also be imposed at state or local levels in some countries. Corporate taxes may be referred to as income tax or capital tax, depending on the nature of the tax.

Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920), was a tax case before the United States Supreme Court that is notable for the following holdings:

In addition to federal income tax collected by the United States, most individual U.S. states collect a state income tax. Some local governments also impose an income tax, often based on state income tax calculations. Forty-two states and many localities in the United States impose an income tax on individuals. Eight states impose no state income tax, and a ninth, New Hampshire, imposes an individual income tax on dividends and interest income but not other forms of income. Forty-seven states and many localities impose a tax on the income of corporations.

Passive income is a type of unearned income that is acquired with minimal labor to earn or maintain. It is often combined with another source of income, such as regular employment or a side job. Passive income, as an acquired income, is taxable.

The Refunding Certificate was a type of interest-bearing banknote that the United States Treasury issued in 1879. They issued it only in the $10 denomination, depicting Benjamin Franklin. Their issuance reflects the end of a coin-hoarding period that began during the American Civil War, and represented a return to public confidence in paper money.

Corporate tax is imposed in the United States at the federal, most state, and some local levels on the income of entities treated for tax purposes as corporations. Since January 1, 2018, the nominal federal corporate tax rate in the United States of America is a flat 21% following the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. State and local taxes and rules vary by jurisdiction, though many are based on federal concepts and definitions. Taxable income may differ from book income both as to timing of income and tax deductions and as to what is taxable. The corporate Alternative Minimum Tax was also eliminated by the 2017 reform, but some states have alternative taxes. Like individuals, corporations must file tax returns every year. They must make quarterly estimated tax payments. Groups of corporations controlled by the same owners may file a consolidated return.

A foreign tax credit (FTC) is generally offered by income tax systems that tax residents on worldwide income, to mitigate the potential for double taxation. The credit may also be granted in those systems taxing residents on income that may have been taxed in another jurisdiction. The credit generally applies only to taxes of a nature similar to the tax being reduced by the credit and is often limited to the amount of tax attributable to foreign source income. The limitation may be computed by country, class of income, overall, and/or another manner.

Anderson County Commissioners v. Beal, 113 U.S. 227 (1885), was a United States Supreme Court case.

Quincy v. Jackson, 113 U.S. 332 (1885), was a writ of error brought to reverse a judgment by the court below by Jackson, a relator, who recovered a judgment against the City of Quincy, Illinois, for the sum of $9,546.24, with costs of suit.

Morgan v. United States, 113 U.S. 476 (1885), was a case involving several judgments of the United States Court of Claims in four cases against the United States for the payment of United States bonds known as "five-twenty bonds."

Boyer v. Boyer, 113 U.S. 689 (1885), was a suit in error brought in a state court of Pennsylvania for an injunction restraining the commissioners of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania from levying a county tax for the year 1883 upon certain shares in the Pennsylvania National Bank, an association organized under the National Banking Act. The suit proceeds upon the ground that such levy violates the act of Congress prescribing conditions upon state taxation of national bank shares in this, that "other moneyed capital in the hands of individual citizens" of that county is exempted by the laws of Pennsylvania from such taxation. A demurrer to the bill was sustained and the suit was dismissed. Upon appeal to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, that judgment was affirmed on the ground that the laws of the state under which the defendants sought to justify the taxation were not repugnant to the act of Congress.

Taxation of income in the United States has been practised since colonial times. Some southern states imposed their own taxes on income from property, both before and after Independence. The Constitution empowered the federal government to raise taxes at a uniform rate throughout the nation, and required that "direct taxes" be imposed only in proportion to the Census population of each state. Federal income tax was first introduced under the Revenue Act of 1861 to help pay for the Civil War. It was renewed in later years and reformed in 1894 in the form of the Wilson-Gorman tariff.

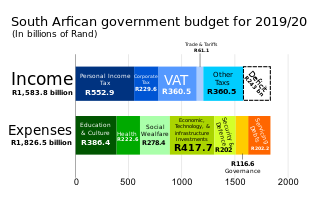

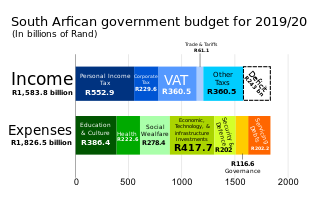

Taxation may involve payments to a minimum of two different levels of government: central government through SARS or to local government. Prior to 2001 the South African tax system was "source-based", where in income is taxed in the country where it originates. Since January 2001, the tax system was changed to "residence-based" wherein taxpayers residing in South Africa are taxed on their income irrespective of its source. Non residents are only subject to domestic taxes.