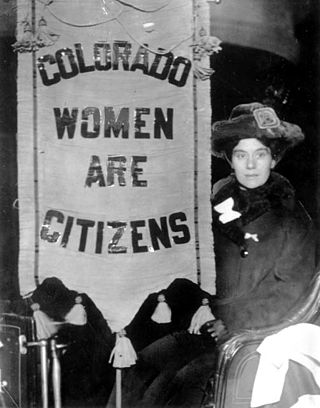

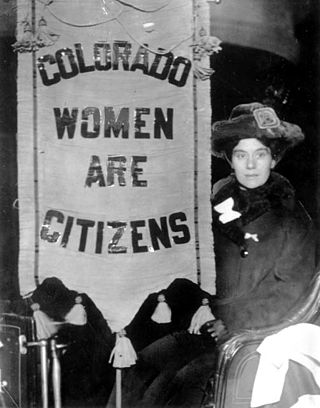

On November 7, 1893, a referendum on women's suffrage was held in Colorado that secured women's voting rights. Subsequently, Colorado became the first American state to enact women's suffrage by popular referendum. The act granted women the right to vote "in the same manner in all respects as male persons are."

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Women's rights issues in Ohio were put into the public eye in the early 1850s. Women inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention created newspapers and then set up their own conventions, including the 1850 Ohio Women's Rights Convention which was the first women's right's convention outside of New York and the first that was planned and run solely by women. These early efforts towards women's suffrage affected people in other states and helped energize the women's suffrage movement in Ohio. Women's rights groups formed throughout the state, with the Ohio Women's Rights Association (OWRA) founded in 1853. Other local women's suffrage groups are formed in the late 1860s. In 1894, women won the right to vote in school board elections in Ohio. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was headquartered for a time in Warren, Ohio. Two efforts to vote on a constitutional amendment, one in 1912 and the other 1914 were unsuccessful, but drew national attention to women's suffrage. In 1916, women in East Cleveland gained the right to vote in municipal elections. A year later, women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus were given the right to vote in municipal elections. Also in 1917, the Reynolds Bill, which would allow women to vote in the next presidential election was passed, and then quickly repealed by a voter referendum sponsored by special-interest groups. On June 16, 1919, Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Ohio. Women's suffrage activism in Ohio began in earnest around the 1850s, when several women's rights conventions took place around the state. The Ohio Women's Convention was very influential on the topic of women's suffrage, and the second Ohio Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, featured Sojourner Truth and her famous speech, Ain't I a Woman? Women worked to create organizations and groups to influence politicians on women's suffrage. Several state constitutional amendments for women's suffrage did not pass. However, women in Ohio did get the right to vote in school board elections and in some municipalities before Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Even before women's suffrage efforts took off in Rhode Island, women were fighting for equal male suffrage during the Dorr Rebellion. Women raised money for the Dorrite cause, took political action and kept members of the rebellion in exile informed. An abolitionist, Paulina Wright Davis, chaired and attended women's rights conferences in New England and later, along with Elizabeth Buffum Chace, founded the Rhode Island Women's Suffrage Association (RIWSA) in 1868. This group petitioned the Rhode Island General Assembly for an amendment to the state constitution to provide women's suffrage. For many years, RIWSA was the major group providing women's suffrage action in Rhode Island. In 1887, a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution came up for a voter referendum. The vote, on April 6, 1887, was decisively against women's suffrage.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Rhode Island. Women's suffrage in Rhode Island started with women's rights activities, such as convention planning and publications of women's rights journals. The first women's suffrage group in Rhode Island was founded in 1868. A women's suffrage amendment was decided by referendum on April 6, 1887, but it failed by a large amount. Finally, in 1917, Rhode Island women gained the right to vote in presidential elections. On January 6, 1920, Rhode Island became the twenty-fourth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Women's suffrage began in Nevada began in the late 1860s. Lecturer and suffragist Laura de Force Gordon started giving women's suffrage speeches in the state starting in 1867. In 1869, Assemblyman Curtis J. Hillyer introduced a women's suffrage resolution in the Nevada Legislature. He also spoke out on women's rights. Hillyer's resolution passed, but like all proposed amendments to the state constitution, must pass one more time and then go out to a voter referendum. In 1870, Nevada held its first women's suffrage convention in Battle Mountain Station. In the late 1880s, women gained the right to run for school offices and the next year several women are elected to office. A few suffrage associations were formed in the mid 1890s, with a state group operating a few women's suffrage conventions. However, after 1899, most suffrage work slowed down or stopped altogether. In 1911, the Nevada Equal Franchise Society (NEFS) was formed. Attorney Felice Cohn wrote a women's suffrage resolution that was accepted and passed the Nevada Legislature. The resolution passed again in 1913 and will go out to the voters on November 3, 1914. Suffragists in the state organized heavily for the 1914 vote. Anne Henrietta Martin brought in suffragists and trade unionists from other states to help campaign. Martin and Mabel Vernon traveled around the state in a rented Ford Model T, covering thousands of miles. Suffragists in Nevada visited mining towns and even went down into mines to talk to voters. On November 3, the voters of Nevada voted overwhelmingly for women's suffrage. Even though Nevada women won the vote, they did not stop campaigning for women's suffrage. Nevada suffragists aided other states' campaigns and worked towards securing a federal suffrage amendment. On February 7, 1920, Nevada became the 28th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Nevada. In 1869, Curtis J. Hillyer introduced a women's suffrage resolution in the Nevada Legislature which passed, though it would wait for another legislative session to approve a second time. The first women's suffrage convention took place in 1870 in Battle Mountain Station. Several women's suffrage resolutions are voted on, or approved, but none complete the criteria to become amendments to the Constitution of Nevada. In the 1880s, women gain the right to run for school offices and several women run and win. Some Nevada women's suffrage groups work throughout the 1890s and hold more conventions. However, most suffrage work slows down or stops around 1899. The Nevada Equal Franchise Society (NEFS) was created in 1911. That same year, Attorney Felice Cohn writes a women's suffrage resolution that is accepted and passed by the Nevada Legislature. Anne Henrietta Martin becomes president of NEFS in 1912. The next year, Cohn's resolution passes a second time and will go out as a voter referendum the next year. On November 3, 1914 Nevada voters approve women's suffrage. Women in Nevada continue to be involved in suffrage campaigning. On February 7, 1920 Nevada ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Maine. Suffragists began campaigning in Maine in the mid 1850s. A lecture series was started by Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was sent that same year. Women continue to fight for equal suffrage throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The Maine Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) is established in 1873 and the next year, the first Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) chapter was started. In 1887, the Maine Legislature votes on a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution, but it does not receive the necessary two-thirds vote. Additional attempts to pass women's suffrage legislation receives similar treatment throughout the rest of the century. In the twentieth century, suffragists continue to organize and meet. Several suffrage groups form, including the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League in 1914 and the Men's Equal Suffrage League of Maine in 1914. In 1917, a voter referendum on women's suffrage is scheduled for September 10, but fails at the polls. On November 5, 1919 Maine ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment. On September 13, 1920, most women in Maine are able to vote. Native Americans in Maine are barred from voting for many years. In 1924, Native Americans became American citizens. In 1954, a voter referendum for Native American voting rights passes. The next year, Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot), is the Native American living on an Indian reservation to cast a vote.

While women's suffrage had an early start in Maine, dating back to the 1850s, it was a long, slow road to equal suffrage. Early suffragists brought speakers Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone to the state in the mid-1850s. Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine, created a women's rights lecture series in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was also sent that year. Working-class women began marching for women's suffrage in the 1860s. The Snow sisters created the first Maine women's suffrage organization, the Equal Rights Association of Rockland, in 1868. In the 1870s, a state suffrage organization, the Maine Women's Suffrage Association (MWSA), was formed. Many petitions for women's suffrage were sent to the state legislature. MWSA and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) of Maine worked closely together on suffrage issues. By the late 1880s the state legislature was considering several women's suffrage bills. While women's suffrage did not pass, during the 1890s many women's rights laws were secured. During the 1900s, suffragists in Maine continued to campaign and lecture on women's suffrage. Several suffrage organizations including a Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League and the Men's Equal Rights League were formed in the 1910s. Florence Brooks Whitehouse started the Maine chapter of the National Woman's Party (NWP) in 1915. Suffragists and other clubwomen worked together on a large campaign for a 1917 voter referendum on women's suffrage. Despite the efforts of women around the state, women's suffrage failed. Going into the next few years, a women's suffrage referendum on voting in presidential elections was placed on the September 13, 1920 ballot. But before that vote, Maine ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on November 5, 1920. It was the nineteenth state to ratify. A few weeks after ratification, MWSA dissolved and formed the League of Women Voters (LWV) of Maine. White women first voted in Maine on September 13, 1920. Native Americans in Maine had to wait longer to vote. In 1924, they became citizens of the United States. However, Maine would not allow individuals living on Indian reservations to vote. It was not until the passage of a 1954 equal rights referendum that Native Americans gained the right to vote in Maine. In 1955 Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot) was the first Native American living on a reservation in Maine to cast a vote.

Attempts to secure women's suffrage in Wisconsin began before the Civil War. In 1846, the first state constitutional convention delegates for Wisconsin discussed women's suffrage and the final document eventually included a number of progressive measures. This constitution was rejected and a more conservative document was eventually adopted. Wisconsin newspapers supported women's suffrage and Mathilde Franziska Anneke published the German language women's rights newspaper, Die Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung, in Milwaukee in 1852. Before the war, many women's rights petitions were circulated and there was tentative work in forming suffrage organizations. After the Civil War, the first women's suffrage conference held in Wisconsin took place in October 1867 in Janesville. That year, a women's suffrage amendment passed in the state legislature and waited to pass the second year. However, in 1868 the bill did not pass again. The Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association (WWSA) was reformed in 1869 and by the next year, there were several chapters arranged throughout Wisconsin. In 1884, suffragists won a brief victory when the state legislature passed a law to allow women to vote in elections on school-related issues. On the first voting day for women in 1887, the state Attorney General made it more difficult for women to vote and confusion about the law led to court challenges. Eventually, it was decided that without separate ballots, women could not be allowed to vote. Women would not vote again in Wisconsin until 1902 after separate school-related ballots were created. In the 1900s, state suffragists organized and continued to petition the Wisconsin legislature on women's suffrage. By 1911, two women's suffrage groups operated in the state: WWSA and the Political Equality League (PEL). A voter referendum went to the public in 1912. Both WWSA and PEL campaigned hard for women's equal suffrage rights. Despite the work put in by the suffragists, the measure failed to pass. PEL and WWSA merged again in 1913 and women continued their education work and lobbying. By 1915, the National Woman's Party also had chapters in Wisconsin and several prominent suffragists joined their ranks. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was also very present in Wisconsin suffrage efforts. Carrie Chapman Catt worked hard to keep Wisconsin suffragists on the path of supporting a federal woman's suffrage amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Wisconsin an hour behind Illinois on June 10, 1919. However, Wisconsin was the first to turn in the ratification paperwork to the State Department.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Wisconsin. Women's suffrage efforts began before the Civil War. The first Wisconsin state constitutional convention in 1846 discussed both women's suffrage and African-American suffrage. In the end, a more conservative constitution was adopted by Wisconsin. In the 1850s, a German language women's rights newspaper was founded in Milwaukee and many suffragists spoke throughout the state. The first state suffrage convention was held in Janesville in 1867. The 1870s, several women's suffrage groups were founded in the state. In 1884, a women's suffrage bill, allowing women to vote for school-related issues is passed. In 1886, voters approve the school-related suffrage bill in a referendum. The first year women vote, 1887, there are challenges to the law that go on until Wisconsin women are allowed to vote again for school issues in 1902 using separate ballots. In the 1900s, women's suffrage conventions continue to take place throughout the state. Women collect petitions and continue to lobby the state legislature. In 1911 Wisconsin legislature passes a bill for women's suffrage that will go out to the voters in 1912. On November 4, 1912 voters disapprove of women's suffrage. Women's suffrage efforts continue, including sponsoring a suffrage school and with the inclusion of a National Woman's Party (NWP) chapter formed in 1915. When the Nineteenth Amendment goes out to the states, Wisconsin ratifies on June 10 and turns in the ratification paperwork first, on June 13, 1919.

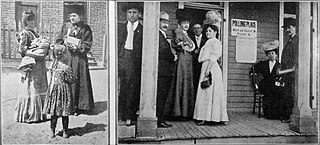

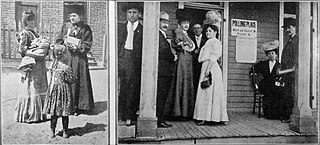

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Colorado. Women's suffrage efforts started in the late 1860s. During the state constitutional convention for Colorado, women received a small win when they were granted the right to vote in school board elections. In 1877, the first women's suffrage referendum was defeated. In 1893, another referendum was successful. After winning the right to vote, Colorado women continued to fight for a federal women's suffrage amendment. While most women were able to vote, it wasn't until 1970 that Native Americans living on reservations were enfranchised.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Pennsylvania. Activists in the state began working towards women's rights in the early 1850s, when two women's rights conventions discussed women's suffrage. A statewide group, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA), was formed in 1869. Other regional groups were formed throughout the state over the years. Suffragists in Pittsburgh created the "Pittsburgh Plan" in 1911. In 1915, a campaign to influence voters to support women's suffrage on the November 2 referendum took place. Despite these efforts, the referendum failed. On June 24, 1919, Pennsylvania became the seventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Pennsylvania women voted for the first time on November 2, 1920.

Women's suffrage began in North Dakota when it was still part of the Dakota Territory. During this time activists worked for women's suffrage, and in 1879, women gained the right to vote at school meetings. This was formalized in 1883 when the legislature passed a law where women would use separate ballots for their votes on school-related issues. When North Dakota was writing its state constitution, efforts were made to include equal suffrage for women, but women were only able to retain their right to vote for school issues. An abortive effort to provide equal suffrage happened in 1893, when the state legislature passed equal suffrage for women. However, the bill was "lost," never signed and eventually expunged from the record. Suffragists continued to hold conventions, raise awareness, and form organizations. The arrival of Sylvia Pankhurst in February 1912 stimulated the creation of more groups, including the statewide Votes for Women League. In 1914, there was a voter referendum on women's suffrage, but it did not pass. In 1917, limited suffrage bills for municipal and presidential suffrage were signed into law. On December 1, 1919, North Dakota became the twentieth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Women's suffrage started in South Dakota when it was part of Dakota Territory. Prior to 1889, it had a shared history of women's suffrage with North Dakota. While South Dakota was part of the territory, women earned the right to vote on school related issues. They retained this right after it became a separate state. The state constitution specified that there would be a women's suffrage amendment referendum in 1890. Despite a large campaign that included Susan B. Anthony and a state suffrage group, the South Dakota Equal Suffrage Association (SDESA), the referendum failed. The state legislature passed additional suffrage referendums over the years, but each was voted down until 1918. South Dakota was an early ratifier of the Nineteenth Amendment, which was approved during a special midnight legislative session on December 4, 1919.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in South Dakota. The early history of women's suffrage in the state is shared with North Dakota. When South Dakota became a state, it held a voter referendum in 1890 on an equal suffrage amendment. This effort failed, but suffragists continued to organize and lobby the legislature to pass voter referendums. None passed until 1918. South Dakota ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on December 4, 1919.

Efforts toward women's suffrage began early in Iowa's history. During the territory's Constitutional Convention, discussions on both African American and women's suffrage took place. Early on, women's rights were discussed in the state by women such as Amelia Bloomer and petitions for suffrage were sent to the Iowa state legislature. While African American men earned the right to vote in 1868, women from all backgrounds had to continue to agitate for enfranchisement. One of the first suffrage groups was formed in Dubuque in 1869. Not long after, a state suffrage convention was held in Mount Pleasant in 1870. Iowa suffragists focused on organizing and lobbying the state legislature. In 1894, women gained the right to vote on municipal bond and tax issues and also in school elections. These rights were immediately utilized by women who turned out in good numbers to vote on these issues. By the 1910s, the state legislature finally passed in successive sessions a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution. This resulted in a voter referendum to be held on the issue on June 5, 1916. The campaign included anti-suffrage agitation from liquor interests who claimed that women's suffrage would cause higher taxes. The amendment was defeated, though a subsequent investigation turned up a large amount of fraud. However, the election could not be invalidated and women had to wait to vote. On July 2, 1919, Iowa became the tenth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Iowa. Women's suffrage work started early in Iowa's history. Organizing began in the late 1960s with the first state suffrage convention taking place in 1870. In the 1890s, women gained the right to vote on municipal bonds, tax efforts and school-related issues. By 1916, a state suffrage amendment went to out to a voter referendum, which failed. Iowa was the tenth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919.