Women played an important part in the Mexican-American War.

Women played an important part in the Mexican-American War.

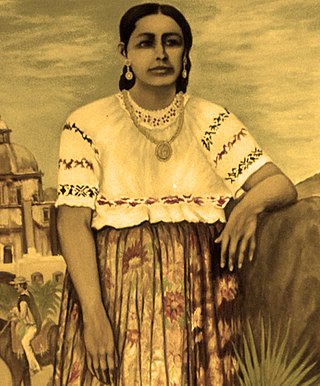

Since Mexico fought the war on its home territory, a traditional support system for troops were women, known as soldaderas . They did not participate in conventional fighting on battlefields, but some soldaderas joined the battle alongside the men. These women were involved in fighting during the defense of Mexico City and Monterrey. Some women such as Doña Jesús Dosamantes and María Josefa Zozaya would be remembered as heroes. [1] Dosamantes was known to have "unsexed" and disguised herself as a captain to fight directly in the face of danger alongside her fellow troops. [2] On the other hand, Zozaya was known to have multiple versions of her story. Some of which included jumping onto rooftops in the city to provide food and munitions to her troops and dying on the battlefield. [3] While Dosamantes and María Josefa Zozaya were seen as die-hard patriots, some Mexican women during the war were described as "angels" as they came to the rescue of all wounded men on both sides. [4] The Mexican women working alongside the male troops faced the same obstacles on the battlefront, however, they were not spared of their duties after returning from battle, for they still had to provide food and clothing. [4] Known as the "shadow army" behind the Mexican force, Mexican women were able to unite by the hundreds behind their fellow soldiers to supply medical needs and boost their morale. [5] On many occasions, soldaderas came to the aid of the opposing army, providing a share of their rations and the clothes on their backs. [6] Constantly on the move between shelters and the battlefield, a soldadera's work was never done. Unlike the Americans who had a negative judgment of soldaderas, their visibility to the Mexican army was not ignored, whether they were coming to the aid of others or leading them into battle. [7]

More often than not, soldaderas had to carry the misconception of solely being seen as servants, especially by American soldiers. Americans had to come to terms with the fact that Mexican women were just as, if not more, patriotic and fearless than their male counterparts. [4] Aside from providing their services during battle, Mexican women were able to do more than what was expected of them domestically. Though they were not ideal circumstances, the war gave Mexican women the opportunity to find new independence within the public sphere. Mexican women were seen pushing the boundaries that were placed onto them by men. To display their pride in defense of their country, Mexican women created their own forms of propaganda. Amongst the faces of the enemy, after the Battle of Monterrey, many Mexican women were seen dressed in “mourning garb and draped their houses in black for three days, as church bells rang funeral tolls." [7] Daniel Harvey Hill, American general, recalled seeing Mexican women paint their men performing domestic duties, such as sewing, while American officials stood by in full dress. [7] Despite their losses, Mexican women still risked their lives in public in order to display their patriotism, aside from risking their lives in battle.

It was not common for American women to join the American forces in combat. Much like Mexican women, they were mostly recognized for their work as laundresses and cooks. However, there were notable American women who stepped out of their private sphere. For instance, Sarah Bowman was unlike most American women in Mexico. Not just for her appearance, but also her role on the battlefield. Standing at six foot two and weighing two hundred pounds, American troops stood in awe of Bowman's muscles and her ability to lift bodies and equipment with ease. [8] Aside from providing food and clothing to the soldiers, many depended on Bowman to transport wounded soldiers to healthcare workers within the forts. [9] When faced with the dangers of bullets flying about and soldiers fighting, Bowman was still seen preparing food, delivering it, and even attacking the enemy. [10]

Prior to the war, New England industries had already expanded on Mexican territory. Therefore, American couples had already made the move to reside in Mexico. [11] When American women were abandoned by their husbands to fight in the war, they were left to uphold the factories. Thus, factory women held supervising positions as well as labor jobs, especially in the textile industry. Among these women who became factory overseers was Ann Chase, another hero to the American forces. As an Irish immigrant, Chase was sympathetic towards the impoverished Mexican cities she resided in, especially Tampico, and even conducted her own research. [12] As American citizens were told to evacuate Tampico, Chase was left to run her husband's business alone as she was exempted due to her British citizenship. [13] Towards the beginning of the war, she was bombarded with increased pressures from Mexican officials to shut down her business and move away. [13] With resentment towards the war, Chase began to send information to U.S. Navy troops upon the whereabouts of Mexican troops: "Her balcony offered an eagle's perch from which to monitor the arrival and departure of troops, their size, point of origin, discipline, and morale." [14] Even though Chase was impressed with the efforts of impoverished Mexican and soldaderas, she was willing to become a spy for U.S. troops if it meant the protection of her home and business. [14]

During the war, it was common for women to travel with their husbands to Mexico. While they had the same domestic duties as Mexican women, oftentimes, American women were hired to be laundresses and servants; American women were getting paid to work. [15] White American women remained in the presence of American troops in terms of medical and domestic service. However, on rare occasions, some American women became prostitutes. [11]

While some American women joined the war effort in Mexico, many were able to contribute from across the border. Whether they were in support or opposition to the war, many women decided to maintain their traditional values. Crafting art, flags, and quilts were among the most common forms for American women to display their patriotism, passing it on to their husbands and sons who had enlisted. [16] However, many American women also took the opportunity to manage their businesses in the absence of men as well as protesting their concerns publicly. [17] Also wanting to make their voices heard within the public sphere, some American women took advantage of their literacy to reach headlines across multiple states.[ citation needed ]

Within the male-dominated journalism space, American women stepped up in support and opposition of the war through their writing nationwide. Among the most prominent was Anne Royall, a Virginian journalist, who did not hold back when it came to speaking up about the war. While her views varied at times, as aggressions grew more violent, she became opposed to the war . [18] Aside from hearing about the tragedies in Mexico, Royall increasingly grew tired of America's fight for expansion, claiming that “the republic was simply becoming too large, too unmanageable." [19] Royall sympathized for Mexican women as she demanded the prosecution of U.S. volunteers who raped and murdered them. [20] Being recognized as the first women political journalist, Royall continued to advocate for women using their voice within the public sphere up until her death in 1854. [20] Also in opposition of the war was Jane Swisshelm, a Pennsylvanian journalist who also advocated for abolitionism and women's rights. After witnessing families being separated due to the war, she began sending angry letters in opposition of the war to the Whig Daily Commercial Journal. [21] Readers were entertained by how Swisshelm wrote with “reckless abandon” and colorful language, claiming that the war was unfair and denouncing anyone who was in support of it. [21] Although they were across the border, both Royall and Swisshelm not only became vessels for the voices of those in opposition of the war, but also Mexican women who were being attacked. On the other hand, Jane Cazneau, a New York editor, became a spy for the Polk administration during the war. Although Cazneau wanted the gruesome fighting to end, she believed that the U.S. would benefit commercially from expansion in Mexico. [22] Deemed as the “Mistress of Manifest Destiny”, Cazneau denounced Mexico's resistance: “Mexico is not true to herself, and even at this hour, she is doing more for the generals of the United States than they can do for themselves. [Mexico] would be more than ready to receive an American government." [23] Although many thought that the war was unfair, Cazneau represented the voices of American women who were in support of the U.S. territorial expansion. Opportunists like Royall, Swisshelm, and Cazneau were seen as independent thinkers during the war and represented the American women who were silenced within the public sphere.[ citation needed ]

The American Revolutionary War, also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a military conflict that was part of the broader American Revolution, where American Patriot forces organized as the Continental Army and commanded by George Washington defeated the British Army.

The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy. The Confederacy had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union. The central conflict leading to the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

The American Revolution was a rebellion and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated an ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy within the British political system as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which successfully ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence, and leading to the creation of the United States of America.

The Battle of Buena Vista, known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between US forces, largely volunteers, under General Zachary Taylor, and the much larger Mexican Army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna. It took place near Buena Vista, a village in the state of Coahuila, about 12 km (7.5 mi) south of Saltillo, Mexico. La Angostura was the local name for the site. The outcome of the battle was ambiguous, with both sides claiming victory. Santa Anna's forces withdrew with war trophies of cannons and flags and left the field to the surprised U.S. forces, who had expected there to be another day of hard fighting.

Maria Isabella Boyd, best known as Belle Boyd was a Confederate spy in the American Civil War. She operated from her father's hotel in Front Royal, Virginia, and provided valuable information to Confederate General Stonewall Jackson in 1862.

The Battle of Harpers Ferry was fought September 12–15, 1862, as part of the Maryland Campaign of the American Civil War. As Confederate Army General Robert E. Lee's Confederate army invaded Maryland, a portion of his army under Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The Battle of the Rosebud took place on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory between the United States Army and its Crow and Shoshoni allies against a force consisting mostly of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne Indians during the Great Sioux War of 1876. The Cheyenne called it the Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother because of an incident during the fight involving Buffalo Calf Road Woman. General George Crook's offensive was stymied by the Indians, led by Crazy Horse, and he awaited reinforcements before resuming the campaign in August.

Loreta Janeta Velázquez was an American woman who wrote that she had masqueraded as a male Confederate soldier during the American Civil War. The book she wrote about her experiences says that after her soldier husband's accidental death, she enlisted in the Confederate States Army in 1861. She then fought at Bull Run, Ball's Bluff, and Fort Donelson, but was discharged when her sex was discovered while in New Orleans. Undeterred, she reenlisted and fought at Shiloh, until unmasked once more. She then became a Confederate spy, working in both male and female guises, and as a double agent also reporting to the U.S. Secret Service. She remarried three more times, being widowed in each instance. According to William C. Davis, she died in January 1923 under the name Loretta J. Beard after many years away from the public eye in a public psychiatric facility, St. Elizabeths Hospital. Most of her claims are not supportable with actual documents, and many are contradictable by actual documentation.

"La Adelita" is one of the most famous corridos of the Mexican Revolution. Over the years, it has had many adaptations. The ballad was inspired by a Chihuahuense woman who joined the Maderista movement in the early stages of the revolution and fell in love with Madero. She became a popular icon and a symbol of the role of women in the Mexican Revolution. The figure of the adelita gradually became synonymous with the term soldadera, the woman in a military-support role, who became a vital force in the revolutionary efforts through provisioning, espionage, and other activities in the battles against Mexican federal government forces.

Soldaderas, often called Adelitas, were women in the military who participated in the conflict of the Mexican Revolution, ranging from commanding officers to combatants to camp followers. "In many respects, the Mexican revolution was not only a men's but a women's revolution." Although some revolutionary women achieved officer status, coronelas, "there are no reports of a woman achieving the rank of general." Since revolutionary armies did not have formal ranks, some women officers were called generala or coronela, even though they commanded relatively few men. A number of women took male identities, dressing as men, and being called by the male version of their given name, among them Ángel Jiménez and Amelio Robles Ávila.

Vivandière or cantinière is a French name for women who are attached to military regiments as sutlers or canteen keepers. Their actual historic functions of selling wine to the troops and working in canteens led to the adoption of the name 'cantinière' which came to supplant the original 'vivandière' starting in 1793. The use of both terms was common in French until the mid-19th century, and 'vivandière' remained the term of choice in non-French-speaking countries such as the US, Spain, Italy, and Great Britain. Vivandières served in the French army up until the beginning of World War I, but the custom spread to many other armies. Vivandières also served on both sides in the American Civil War, and in the armies of Spain, Italy, the German states, Switzerland, and various armies in South America, though little is known about the details in most of those cases as historians have not done extensive research on them.

Women in the American Revolution played various roles depending on their social status, race and political views.

355 was the supposed code name of a female spy during the American Revolution who was part of the Culper Ring spy network. She was one of the first spies for the United States, but her real identity is unknown. The number 355 could be decrypted from the system the Culper Ring used to mean "lady." Her story is considered part of national myth, as there is very little evidence that 355 even existed, although many continue to assert that she was a real historical figure.

During the American Civil War, sexual behavior, gender roles, and attitudes were affected by the conflict, especially by the absence of menfolk at home and the emergence of new roles for women such as nursing. The advent of photography and easier media distribution, for example, allowed for greater access to sexual material for the common soldier.

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, was an invasion of Mexico by the United States Army from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 American annexation of Texas, which Mexico still considered its territory because Mexico refused to recognize the Treaties of Velasco, signed by President Antonio López de Santa Anna after he was captured by the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its Anglo-American citizens who had moved from the United States to Texas after 1822 wanted to be annexed by the United States.

This is a timeline of women in warfare in the United States before 1900.This list includes women who served in the United States Armed Forces in various roles. It also includes women who have been Warriors and fighters in other types of conflicts that have taken place in the United States. This list should also encompass women who served in support roles during military and other conflicts in the United States before the twentieth century.

This is a timeline of women in warfare in the United States up until the end of World War II. It encompasses the colonial era and indigenous peoples, as well as the entire geographical modern United States, even though some of the areas mentioned were not incorporated into the United States during the time periods that they were mentioned.

Antonia Nava de Catalán was a heroine of the Mexican War of Independence. She accompanied her husband, a volunteer who rose to the rank of colonel, throughout the war. Three of her sons were killed in the struggle. She is remembered for her willingness to sacrifice her family and herself to achieve independence from Spain, and came to be known as "La Generala". She fought alongside Jose Maria Morales until her death.

Ignacia Reachy (1816–1866) was a soldier during the War of Intervention.