"Jabberwocky" is a nonsense poem written by Lewis Carroll about the killing of a creature named "the Jabberwock". It was included in his 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). The book tells of Alice's adventures within the back-to-front world of the Looking-Glass world.

A nursery rhyme is a traditional poem or song for children in Britain and many other countries, but usage of the term dates only from the late 18th/early 19th century. The term Mother Goose rhymes is interchangeable with nursery rhymes.

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There is a novel published on 27 December 1871 by Lewis Carroll, a mathematics lecturer at Christ Church, University of Oxford, and the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Alice again enters a fantastical world, this time by climbing through a mirror into the world that she can see beyond it. There she finds that, just like a reflection, everything is reversed, including logic.

"Little Bo-Peep" or "Little Bo-Peep has lost her sheep" is a popular English language nursery rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 6487.

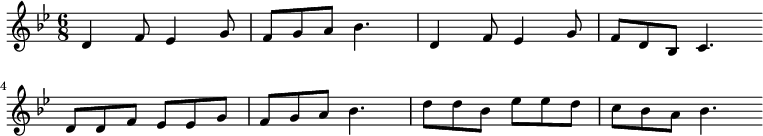

"Hey Diddle Diddle" is an English nursery rhyme. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 19478.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee are characters in an English nursery rhyme and in Lewis Carroll's 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. Their names may have originally come from an epigram written by poet John Byrom. The nursery rhyme has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 19800. The names have since become synonymous in western popular culture slang for any two people whose appearances and actions are identical.

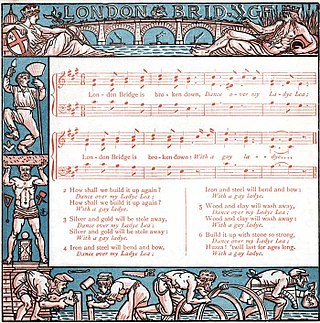

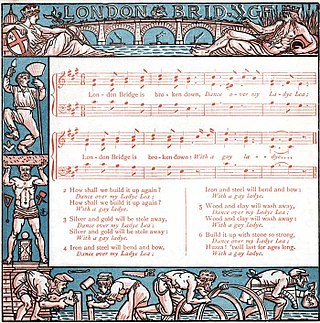

"London Bridge Is Falling Down" is a traditional English nursery rhyme and singing game, which is found in different versions all over the world. It deals with the dilapidation of London Bridge and attempts, realistic or fanciful, to repair it. It may date back to bridge-related rhymes and games of the Late Middle Ages, but the earliest records of the rhyme in English are from the 17th century. The lyrics were first printed in close to their modern form in the mid-18th century and became popular, particularly in Britain and the United States, during the 19th century.

"Ring a Ring o' Roses", "Ring a Ring o' Rosie", or "Ring Around the Rosie", is a nursery rhyme, folk song and playground singing game. Descriptions first emerge in the mid-19th century, but are reported as dating from decades before, and similar rhymes are known from across Europe, with various lyrics. It has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 7925.

The Big Over Easy is a 2005 novel written by Jasper Fforde. It features Detective Inspector Jack Spratt and his assistant, Sergeant Mary Mary.

The Lion and the Unicorn are symbols of the United Kingdom. They are, properly speaking, heraldic supporters appearing in the full royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom. The lion stands for England and the unicorn for Scotland. The combination therefore dates back to the 1603 accession of James I of England who was already James VI of Scotland. By extension, they are also used in the arms of Newfoundland since 1637, the arms of Hanover between 1837–1866, and the arms of Canada since 1921.

The siege of Colchester occurred in the summer of 1648 when the Second English Civil War reignited in several areas of Britain. Colchester found itself in the thick of the unrest when a Royalist army on its way through East Anglia to raise support for the King, was attacked by Lord-General Thomas Fairfax at the head of a Parliamentary force. The Parliamentarians' initial attack forced the Royalist army to retreat behind the town's walls, but they were unable to bring about victory, so they settled down to a siege. Despite the horrors of the siege, the Royalists resisted for eleven weeks and only surrendered following the defeat of the Royalist army in the North of England at the Battle of Preston (1648).

The siege of Gloucester took place between 10 August and 5 September 1643 during the First English Civil War. It was part of a Royalist campaign led by King Charles I to take control of the Severn Valley from the Parliamentarians. Following the costly storming of Bristol on 26 July, Charles invested Gloucester in the hope that a show of force would prompt it to surrender quickly and without bloodshed. When the city, under the governorship of Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Massey, refused, the Royalists attempted to bombard it into submission. Massey adopted an aggressive defence, and the Royalist positions outside the city were regularly disrupted by Parliamentarian raids. The Royalist artillery proved inadequate for the task of siege work and, faced with a shortage of ammunition, the besiegers attempted to breach the city walls by mining. With Royalist miners about to reach the city's east gate and the defenders critically low on gunpowder, a Parliamentarian army led by the Earl of Essex arrived and forced Charles to lift the siege.

Alice in Wonderland is a musical by Henry Savile Clarke and Walter Slaughter (music), based on Lewis Carroll's books Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). It debuted at the Prince of Wales's Theatre in the West End on 23 December 1886. Aubrey Hopwood (lyrics) and Walter Slaughter (music) wrote additional songs which were first used for the 1900 revival.

The Golden Boughs Retirement Village is a fictional prison masquerading as a retirement home for fables in the Fables spin-off Jack of Fables. It is run by a man called himself Mr. Revise. The name is an explicit reference to The Golden Bough, a lengthy study in the comparative mythology, religion and folklore of hundreds of cultures, from aboriginal and extinct cultures to 19th-century faiths.

Llanthony Secunda Priory was a house of Augustinian canons in the parish of Hempsted, Gloucestershire, England, situated about 1/2 a mile south-west of Gloucester Castle in the City of Gloucester. It was founded in 1136 by Miles de Gloucester, 1st Earl of Hereford, a great magnate based in the west of England and the Welsh Marches, hereditary Constable of England and Sheriff of Gloucestershire, as a secondary house and refuge for the canons of Llanthony Priory in the Vale of Ewyas, within his Lordship of Brecknock in what is now Monmouthshire, Wales. The surviving remains of the Priory were designated as Grade I listed in 1952 and the wider site is a scheduled ancient monument. In 2013 the Llanthony Secunda Priory Trust received funds for restoration work which was completed in August 2018 when it re-opened to the public.

Mots D'Heures: Gousses, Rames: The D'Antin Manuscript, published in 1967 by Luis d'Antin van Rooten, is purportedly a collection of poems written in archaic French with learned glosses. In fact, they are English-language nursery rhymes written homophonically as a nonsensical French text ; that is, as an English-to-French homophonic translation. The result is not merely the English nursery rhyme but that nursery rhyme as it would sound if spoken in English by someone with a strong French accent. Even the manuscript's title, when spoken aloud, sounds like "Mother Goose Rhymes" with a strong French accent; it literally means "Words of Hours: Pods, Paddles."

Homophonic translation renders a text in one language into a near-homophonic text in another language, usually with no attempt to preserve the original meaning of the text. In one homophonic translation, for example, the English "sat on a wall" is rendered as French "s'étonne aux Halles". More generally, homophonic transformation renders a text into a near-homophonic text in the same or another language: e.g., "recognize speech" could become "wreck a nice beach".

The News at Bedtime is a satirical comedy series on BBC Radio 4 written by Ian Hislop and Nick Newman, writers of the satirical Private Eye magazine. The series is a spoof of news programs, in particular shows such as The Today Programme, set in "Nurseryland", a place in which all nursery rhymes and children's stories are real. The News at Bedtime stars Jack Dee and Peter Capaldi as the main newsreaders, John Tweedledum and Jim Tweedledee. The series was broadcast over the Christmas period in 2009, from Christmas Eve 2009 to New Year's Day 2010 with a special "Year in Review" episode broadcast on 31 December 2010.

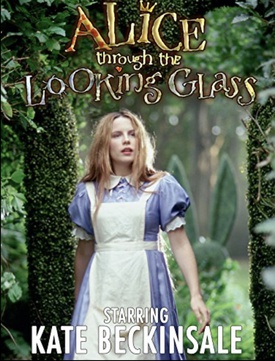

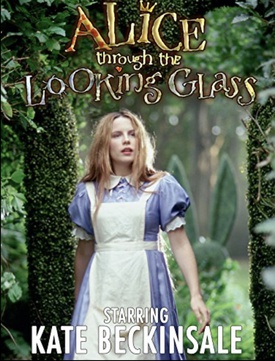

Alice through the Looking Glass is a 1998 British fantasy television film, based on Lewis Carroll's 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass, and starring Kate Beckinsale.

"Arthur o' Bower" is a short British nursery rhyme or rhymed riddle originally published in 1805 but known, on the evidence of a letter by William Wordsworth, to have been current in the late 18th century in Cumberland. The title character is a personification of a storm wind, sometimes believed to represent King Arthur in his character as storm god or leader of the Wild Hunt. The Roud Folk Song Index, which catalogues folk songs and their variations by number, classifies this rhyme as 22839.