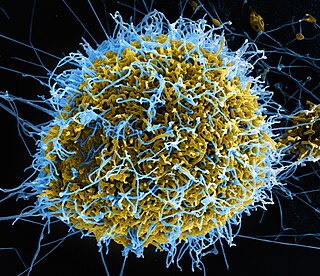

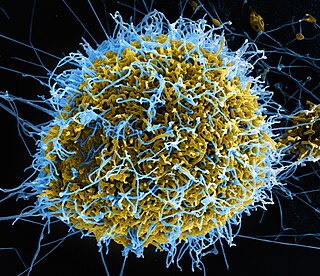

Marburg virus disease is a viral hemorrhagic fever in human and non-human primates caused by either of the two Marburgviruses: Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). Its clinical symptoms are very similar to those of Ebola virus disease (EVD).

Health in Uganda refers to the health of the population of Uganda. The average life expectancy at birth of Uganda has increased from 59.9 years in 2013 to 63.4 years in 2019. This is lower than in any other country in the East African Community except Burundi. As of 2017, females had a life expectancy higher than their male counterparts of 69.2 versus 62.3. It is projected that by 2100, males in Uganda will have an expectancy of 74.5 and females 83.3. Uganda's population has steadily increased from 36.56 million in 2016 to an estimate of 42.46 in 2021. The fertility rate of Ugandan women slightly increased from an average of 6.89 babies per woman in the 1950s to about 7.12 in the 1970s before declining to an estimate 5.32 babies in 2019. This figure is higher than most world regions including South East Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Europe and Central Asia and America. The under-5-mortality-rate for Uganda has decreased from 191 deaths per 1000 live births in 1970 to 45.8 deaths per 1000 live births in 2019.

Passive immunity is the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and it can also be induced artificially, when high levels of antibodies specific to a pathogen or toxin are transferred to non-immune persons through blood products that contain antibodies, such as in immunoglobulin therapy or antiserum therapy. Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response, or to reduce the symptoms of ongoing or immunosuppressive diseases. Passive immunization can be provided when people cannot synthesize antibodies, and when they have been exposed to a disease that they do not have immunity against.

Frederick Wabwire-Mangen is a Ugandan physician, public health specialist and medical researcher. Currently he is Professor of Epidemiology and Head of Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics at Makerere University School of Public Health. Wabwire-Mangen also serves as the Chairman of Council of Kampala International University and a founding member of Accordia Global Health Foundation’s Academic Alliance

Marburg virus (MARV) is a hemorrhagic fever virus of the Filoviridae family of viruses and a member of the species Marburg marburgvirus, genus Marburgvirus. It causes Marburg virus disease in primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic fever. The virus is considered to be extremely dangerous. The World Health Organization (WHO) rates it as a Risk Group 4 Pathogen. In the United States, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases ranks it as a Category A Priority Pathogen and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists it as a Category A Bioterrorism Agent. It is also listed as a biological agent for export control by the Australia Group.

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection. The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function, at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average. Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear. Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start. An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been used extensively in the Kivu Ebola epidemic under a compassionate use protocol. During the early 21st century, several vaccine candidates displayed efficacy to protect nonhuman primates against lethal infection.

Elioda Tumwesigye is a Ugandan politician, physician, and epidemiologist who has served as minister of science, technology and innovation in the cabinet of Uganda since June 2016. From March 2015 until June 2016, he served as the minister of health.

Post-Ebola virus syndrome is a post-viral syndrome affecting those who have recovered from infection with Ebola. Symptoms include joint and muscle pain, eye problems, including blindness, various neurological problems, and other ailments, sometimes so severe that the person is unable to work. Although similar symptoms had been reported following previous outbreaks in the last 20 years, health professionals began using the term in 2014 when referring to a constellation of symptoms seen in people who had recovered from an acute attack of Ebola disease.

Ring vaccination is a strategy to inhibit the spread of a disease by vaccinating those who are most likely to be infected.

On 20 January 2016, the health minister of Angola reported 23 cases of yellow fever with 7 deaths among Eritrean and Congolese citizens living in Angola in Viana municipality, a suburb of the capital of Luanda. The first cases were reported in Eritrean visitors beginning on 5 December 2015 and confirmed by the Pasteur WHO reference laboratory in Dakar, Senegal in January. The outbreak was classified as an urban cycle of yellow fever transmission, which can spread rapidly. A preliminary finding that the strain of the yellow fever virus was closely related to a strain identified in a 1971 outbreak in Angola was confirmed in August 2016. Moderators from ProMED-mail stressed the importance of initiating a vaccination campaign immediately to prevent further spread. The CDC classified the outbreak as Watch Level 2 on 7 April 2016. The WHO declared it a grade 2 event on its emergency response framework having moderate public health consequences.

The 2017 Uganda Marburg virus outbreak was confirmed by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 20 October 2017 after there had been an initial fatality due to the virus.

The 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak occurred in the north-west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from May to July 2018. It was contained entirely within Équateur province, and was the first time that vaccination with the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak, with a total of 3,481 people vaccinated. It was the ninth recorded Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

The Kivu Ebola epidemic was an outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) mainly in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and in other parts of Central Africa, from 2018 to 2020. Between 1 August 2018 and 25 June 2020 it resulted in 3,470 reported cases. The Kivu outbreak also affected Ituri Province, whose first case was confirmed on 13 August 2018. In November 2018, the outbreak became the biggest Ebola outbreak in the DRC's history, and had become the second-largest Ebola outbreak in recorded history worldwide, behind only the 2013–2016 Western Africa epidemic. In June 2019, the virus reached Uganda, having infected a 5-year-old Congolese boy who entered Uganda with his family, but was contained.

Maria DeJoseph Van Kerkhove is an American infectious disease epidemiologist. With a background in high-threat pathogens, Van Kerkhove specializes in emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases and is based in the Health Emergencies Program at the World Health Organization (WHO). She is the technical lead of COVID-19 response and the head of emerging diseases and zoonosis unit at WHO.

Caitlin M. Rivers is an American epidemiologist who as Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, specializing on improving epidemic preparedness. Rivers is currently working on the American response to the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on the incorporation of infectious disease modeling and forecasting into public health decision making.

Maimuna (Maia) Majumder is a computational epidemiologist and a faculty member at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital's Computational Health Informatics Program (CHIP). She is currently working on modeling the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On 7 February 2021, the Congolese health ministry announced that a new case of Ebola near Butembo, North Kivu had been detected the previous day. The case was a 42-year-old woman who had symptoms of Ebola in Biena on 1 February 2021. A few days after, she died in a hospital in Butembo. The WHO said that more than 70 people who had contact with the woman had been tracked.

The 2022-2023 Uganda Ebola outbreak was an outbreak of the Sudan ebolavirus, which causes Ebola, from 20 September 2022 until 10 January 2023 in the Western and Central Regions of Uganda. Over 160 people were infected, including 77 people who died. It was Uganda's fifth outbreak with Sudan ebolavirus. The Ugandan Ministry of Health declared the outbreak on 20 September 2022. As of 25 October 2022, there were confirmed cases in the Mubende, Kyegegwa, Kassanda, Kagadi, Bunyanga, Kampala and Wakiso districts. As of 24 October 2022, there were a total of 90 confirmed or probable cases and 44 deaths. On 12 October, the first recorded death in the capital of Kampala occurred; 12 days later on 24 October, there had been a total of 14 infections in the capital in the last two days. On 11 January 2023 after 42 days without new cases the outbreak was declared over.