The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC. In the Ancient Near East, it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age. The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era: The first half of the millennium is dominated by the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and Babylonia. The alphabet develops. At the center of the millennium, a new order emerges with Mycenaean Greek dominance of the Aegean and the rise of the Hittite Empire. The end of the millennium sees the Bronze Age collapse and the transition to the Iron Age.

Mycenae is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about 120 kilometres south-west of Athens; 11 kilometres north of Argos; and 48 kilometres south of Corinth. The site is 19 kilometres inland from the Saronic Gulf and built upon a hill rising 900 feet above sea level.

The 13th century BC was the period from 1300 to 1201 BC.

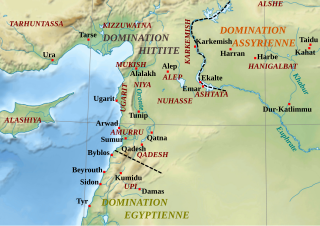

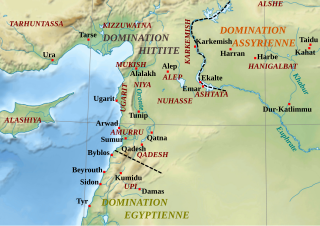

Mitanni, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or Naharin in Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia with Indo-Aryan linguistic and political influences. Since no histories, royal annals or chronicles have yet been found in its excavated sites, knowledge about Mitanni is sparse compared to the other powers in the area, and dependent on what its neighbours commented in their texts.

Ugarit was an ancient port city in northern Syria about 10 kilometers north of modern Latakia. At its height it ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern Latakia Governorate. It was discovered by accident in 1928 with the Ugaritic texts. Its ruins are often called Ras Shamra after the headland where they lie.

Tiryns is a Mycenaean archaeological site in Argolis in the Peloponnese, and the location from which the mythical hero Heracles was said to have performed his Twelve Labours. It lies 20 km (12 mi) south of Mycenae.

Mycenaean Greece was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland Greece with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art, and writing system. The Mycenaeans were mainland Greek peoples who were likely stimulated by their contact with insular Minoan Crete and other Mediterranean cultures to develop a more sophisticated sociopolitical culture of their own. The most prominent site was Mycenae, after which the culture of this era is named. Other centers of power that emerged included Pylos, Tiryns, and Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, and Athens in Central Greece, and Iolcos in Thessaly. Mycenaean settlements also appeared in Epirus, Macedonia, on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, and on Cyprus, while Mycenaean-influenced settlements appeared in the Levant and Italy.

Qatna was an ancient city located in Homs Governorate, Syria. Its remains constitute a tell situated about 18 km (11 mi) northeast of Homs near the village of al-Mishrifeh. The city was an important center through most of the second millennium BC and in the first half of the first millennium BC. It contained one of the largest royal palaces of Bronze Age Syria and an intact royal tomb that has provided a great amount of archaeological evidence on the funerary habits of that period.

Wilusa or Wilusiya was a Late Bronze Age city in western Anatolia known from references in fragmentary Hittite records. The city is notable for its identification with the archaeological site of Troy, and thus its potential connection to the legendary Trojan War.

Helladic chronology is a relative dating system used in archaeology and art history. It complements the Minoan chronology scheme devised by Sir Arthur Evans for the categorisation of Bronze Age artefacts from the Minoan civilization within a historical framework. Whereas Minoan chronology is specific to Crete, the cultural and geographical scope of Helladic chronology is confined to mainland Greece during the same timespan. Similarly, a Cycladic chronology system is used for artifacts found in the Aegean islands. Archaeological evidence has shown that, broadly, civilisation developed concurrently across the whole region and so the three schemes complement each other chronologically. They are grouped together as "Aegean" in terms such as Aegean art and, rather more controversially, Aegean civilization.

Maşat Höyük is a Bronze Age Hittite archaeological site 100 km nearly east of Boğazkale/Hattusa, about 20 km south of Zile, Tokat Province, north-central Turkey, not far from the Çekerek River. The site is under agricultural use and is plowed. It was first excavated in the 1970s.

Niqmaddu II was the second ruler and king of Ugarit, an ancient Syrian citystate in northwestern Syria, reigning c. 1350–1315 BC and succeeding his less known father, Ammittamru I. He took his name from the earlier Amorite ruler Niqmaddu, meaning "Addu has vindicated" to strengthen the supposed Amorite origins of his Ugaritic dynasty.

Nuhašše, was a region in northwestern Syria that flourished in the 2nd millennium BC. It was east of the Orontes River bordering Aleppo (northwest) and Qatna (south). It was a petty kingdom or federacy of principalities probably under a high king. Tell Khan Sheykhun has tenatively been identifed as kurnu-ḫa-šeki.

The Middle Bronze Age Migrations are postulated waves of migration during the Middle Bronze Age. This proposal was advanced in the mid-20th century by scholars such as Mellaart, who argued for a connection between the spread of the Indo-European languages and archaeologically attested destructions and cultural changes around the 20th century BC. However, more recent research has disfavored the notion of Indo-European invasions, interpreting the evidence as favoring a more gradual process of assimilation.

Grave Circle A is a 16th-century BC royal cemetery situated to the south of the Lion Gate, the main entrance of the Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae in southern Greece. This burial complex was initially constructed outside the walls of Mycenae and ultimately enclosed in the acropolis when the fortification was extended during the 13th century BC. Grave Circle A and Grave Circle B, the latter found outside the walls of Mycenae, represents one of the significant characteristics of the early phase of the Mycenaean civilization.

The Royal Palace of Ugarit was the royal residence of the rulers of the ancient kingdom of Ugarit on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. The palace was excavated with the rest of the city from the 1930s by French archaeologist Claude F. A. Schaeffer and is considered one of the most important finds made at Ugarit.

Attarsiya was an Ahhiyan warlord who lived around 1400 BC. He is known from a single Hittite text, which recounts his military activities in Western Anatolia and Alasiya. These texts are significant because they provide the earliest textual evidence of Mycenaean Greek involvement in Western Anatolian affairs. Scholars have noted potential connections between his name and that of Atreus from Greek mythology.

The military nature of Mycenaean Greece in the Late Bronze Age is evident by the numerous weapons unearthed, warrior and combat representations in contemporary art, as well as by the preserved Greek Linear B records. The Mycenaeans invested in the development of military infrastructure with military production and logistics being supervised directly from the palatial centres.

Adad-Nirari or Addu-Nirari was a king of Nuhašše in the 14th century BC. His identity and succession order is debated as well as the extent of his kingdom which might have included Qatna. Adad-Nirari engaged in a military struggle again the Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I, asking Egypt for help and invading the kingdom of Ugarit, a Hittite vassal. Those actions prompted Šuppiluliuma to invade the region and relive Ugarit. Adad-Nirari's fate is unknown as he disappeared from records.