The 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes were a series of intense intraplate earthquakes beginning with an initial earthquake of moment magnitude 7.2–8.2 on December 16, 1811, followed by a moment magnitude 7.4 aftershock on the same day. Two additional earthquakes of similar magnitude followed in January and February 1812. They remain the most powerful earthquakes to hit the contiguous United States east of the Rocky Mountains in recorded history. The earthquakes, as well as the seismic zone of their occurrence, were named for the Mississippi River town of New Madrid, then part of the Louisiana Territory and now within the U.S. state of Missouri.

John Winthrop was an American mathematician, physicist and astronomer. He was the 2nd Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in Harvard College.

The Fukuoka earthquake struck Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan at 10:53 am JST on March 20, 2005, and lasted for approximately 1 minute. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) measured it as peaking at a magnitude of 7.0, whereas the United States Geological Survey (USGS) reported a magnitude of 6.6. The quake occurred along a previously unknown fault in the Genkai Sea, North of Fukuoka city, and the residents of Genkai Island were forced to evacuate as houses collapsed and landslides occurred in places. Investigations subsequent to the earthquake determined that the new fault was most likely an extension of the known Kego fault that runs through the centre of the city.

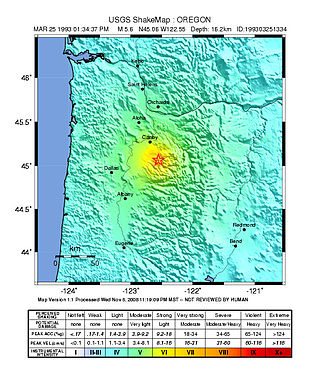

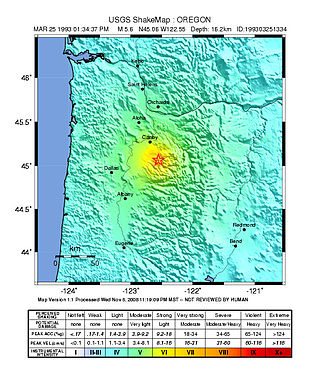

The 1993 Scotts Mills earthquake, also known as the "Spring break quake", occurred in the U.S. state of Oregon on March 25 at 5:34 AM Pacific Standard Time. With a moment magnitude of 5.6 and a maximum perceived intensity of VII on the Mercalli intensity scale, it was the largest earthquake in the Pacific Northwest since the Elk Lake and Goat Rocks earthquakes of 1981. Ground motion was widely felt in Oregon's Willamette Valley, the Portland metropolitan area, and as far north as the Puget Sound area near Seattle, Washington.

The 1952 Kern County earthquake occurred on July 21 in the southern San Joaquin Valley and measured 7.3 on the moment magnitude scale. The main shock occurred at 4:52 am Pacific Daylight Time, killed 12 people, injured hundreds more and caused an estimated $60 million in property damage. A small sector of damage near Bealville corresponded to a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme), though this intensity rating was not representative of the majority of damage. The earthquake occurred on the White Wolf Fault near the community of Wheeler Ridge and was the strongest to occur in California since the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

The 1935 Temiskamingue earthquake occurred on November 1 with a moment magnitude of 6.1 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII. The event took place in the Western Quebec Seismic Zone in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region of Quebec.

The 1944 Cornwall–Massena earthquake occurred on September 5 at 12:38:45 am EDT in Massena, New York. It registered 5.8 on the moment magnitude scale and had a maximum Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe). This area is part of the Saint Lawrence River Valley and the seismically active zone known as the Saint Lawrence rift system. The earthquake is the largest known in New York's recorded history and was felt over great distances.

The 1968 Illinois earthquake was the largest recorded earthquake in the U.S. Midwestern state of Illinois. Striking at 11:02 am on November 9, it measured 5.4 on the Richter scale. Although no fatalities occurred, the event caused considerable structural damage to buildings, including the toppling of chimneys and shaking in Chicago, the region's largest city. The earthquake was one of the most widely felt in U.S. history, largely affecting 23 states over an area of 580,000 sq mi (1,500,000 km2). In studying its cause, scientists discovered the Cottage Grove Fault in the Southern Illinois Basin.

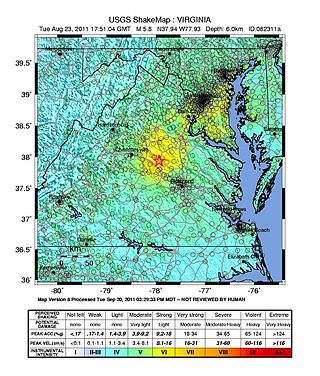

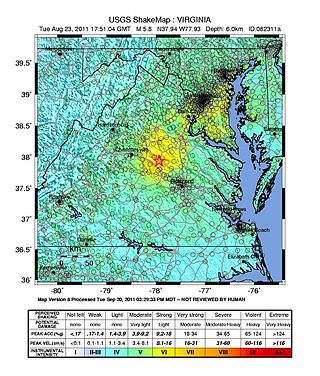

On August 23, 2011, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake hit the Piedmont region of the U.S. state of Virginia at 1:51:04 p.m. EDT. The epicenter, in Louisa County, was 38 mi (61 km) northwest of Richmond and 5 mi (8 km) south-southwest of the town of Mineral. It was an intraplate earthquake with a maximum perceived intensity of VIII (Severe) on the Mercalli intensity scale. Several aftershocks, ranging up to 4.5 in magnitude, occurred after the main tremor.

The geology of New Hampshire is similar to that of the rest of New England in comprising a series of metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Late Proterozoic to Devonian age, intruded by many plutons and dikes ranging in age from Late Proterozoic to early Cretaceous. New Hampshire is known as "the Granite State", but less than half is underlain by granite; much of it is schist or gneiss, both of which are metamorphic rocks.

The 1918 San Jacinto earthquake occurred in extreme eastern San Diego County in Southern California on April 21 at . The shock had a moment magnitude of 6.7 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent). Several injuries and one death occurred with total losses estimated to be $200,000.

The 1936 State Line earthquake struck at 23:08 Pacific time on July 15, 1936. The earthquake had an estimated magnitude of 5.8 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII. The epicenter was near the Oregon/Washington state line approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) northwest of Milton-Freewater, Oregon and southwest of Walla Walla, Washington and was felt throughout the Pacific Northwest, including as far away as Bonners Ferry, Idaho near the Canadian border and by seismographs as far away as San Diego, California.

The 2019 Batanes earthquake was a magnitude 6.0 earthquake which struck Batanes, Philippines on July 27, 2019. It was preceded by a 5.4 magnitude foreshock. Nine people were killed by the combined effects of the earthquakes.

The 2020 Central Idaho earthquake occurred in the western United States on March 31, 2020, at 5:52 PM MDT, near Ruffneck Peak in the Sawtooth Mountains of central Idaho, 72 miles (116 km) northeast of Boise and 19 miles (31 km) northwest of Stanley. It had a magnitude of 6.5 and was felt with a maximum intensity of VIII.

The 1921 Sevier Valley earthquake was a series of three earthquakes. The primary quake was a magnitude 6.3 earthquake that occurred on Thursday, 29 September 1921 at approximately 7:12 AM MT in Elsinore, Utah, United States. The first aftershock occurred in the evening on the same day, and a second aftershock occurred two days later on 1 October. No people were killed in the quake or in the subsequent aftershocks.

The 2020 Sparta earthquake was a relatively uncommon intraplate earthquake that occurred near the small town of Sparta, North Carolina, on August 9, 2020 at 8:07 am local time. The earthquake had a moment magnitude of 5.1, and a shallow depth of 7.6 kilometers (4.7 mi). Shaking was reported throughout the Southern, Midwestern, and Northeastern United States. It was the strongest earthquake recorded in North Carolina in 104 years, the second-strongest in the state's history, and the largest to strike the East Coast since the 2011 Virginia earthquake.

The 1870 Charlevoix earthquake occurred on 20 October in the Canadian province of Quebec. It had a moment magnitude of 6.6 Mw and a Modified Mercalli intensity rating of X (Extreme). The town of Baie-Saint-Paul was seriously damaged by the event, with the loss of six lives. Effects from the earthquake were felt as far as Virginia and along the New England coast of the United States.

The 1895 Charleston earthquake, also known as the Halloween earthquake, occurred on October 31, at 05:07 CST near Charleston, Missouri. It had an estimated moment magnitude of 5.8–6.6 and evaluated Modified Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe). The earthquake caused substantial property damage in the states of Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, Alabama, Iowa, Kentucky, Indiana, and Tennessee. Shaking was widespread, being felt across 23 states and even in Canada. At least two people died and seven were injured.