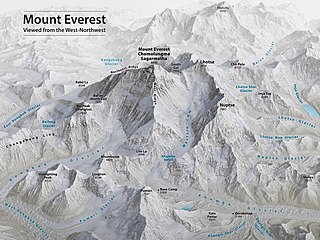

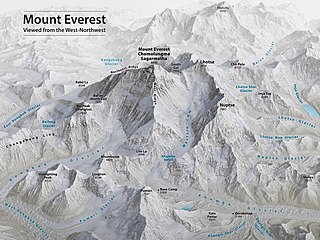

Changtse is a mountain situated between the Main Rongbuk and East Rongbuk Glaciers in Tibet Autonomous Region, China, immediately north of Mount Everest. It is connected to Mount Everest via the North Col.

Eric Earle Shipton, CBE, was an English Himalayan mountaineer.

Major Harold William Tilman, CBE, DSO, MC and Bar, was an English mountaineer and explorer, renowned for his Himalayan climbs and sailing voyages.

Maurice Wilson MC was a British soldier, mystic, and aviator who is known for his ill-fated attempt to climb Mount Everest alone in 1934.

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain, with a peak at 8,849 metres (29,031.7 ft) above sea level. It is situated in the Himalayan range of Solukhumbu district, Nepal.

Hugh Ruttledge was an English civil servant and mountaineer who was the leader of two expeditions to Mount Everest in 1933 and 1936.

The 1924 British Mount Everest expedition was—after the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition—the 2nd expedition with the goal of achieving the first ascent of Mount Everest. After two summit attempts in which Edward Norton set a world altitude record of 28,126 feet (8572 m), the mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine disappeared on the third attempt. Their disappearance has given rise to the long-standing unanswered question of whether or not the pair climbed to the summit. Mallory's body was found in 1999 at 26,760 feet (8155 m), but the resulting clues did not provide conclusive evidence as to whether the summit was reached.

The 1933 British Mount Everest expedition was, after the reconnaissance expedition of 1921, and the 1922 and 1924 expeditions, the fourth British expedition to Mount Everest and the third with the intention of making the first ascent.

The 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition set off to explore how it might be possible to get to the vicinity of Mount Everest, to reconnoitre possible routes for ascending the mountain, and – if possible – make the first ascent of the highest mountain in the world. At that time Nepal was closed to foreigners, so any approach had to be from the north, through Tibet. A feasible route was discovered from the east up the Kharta Glacier and then crossing the Lhakpa La pass north east of Everest. It was then necessary to descend to the East Rongbuk Glacier before climbing again to Everest's North Col. However, although the North Col was reached, it was not possible to climb further before the expedition had to withdraw.

The Lho La is a col on the border between Nepal and Tibet north of the Western Cwm, near Mount Everest. It is at the lowest point of the West Ridge of the mountain at a height of 6,006 metres (19,704 ft).

Lingtren, 6,749 metres (22,142 ft), is a mountain in the Mahalangur Himal area of Himalaya, about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) distant in a direct line from Mount Everest. It lies on the international border between Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China and it was first climbed in 1935. A mountain nearby to the west was originally named Lingtrennup but is now more commonly called Xi Lingchain.

Major General John Geoffrey Bruce was an officer in the British Indian Army, eventually becoming Deputy Chief of General Staff, who participated in the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition. Bruce, who had never before climbed a mountain, had been appointed as a transport officer, but chance led to him accompanying George Finch on the only summit attempt that used supplemental oxygen. Together they set a new mountaineering world record height of 8,300 metres (27,300 ft), only 520 metres (1,700 ft) below the summit of Mount Everest.

Precipitated by unexpected permission from Tibet, the 1935 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition was planned at short notice as a preliminary to an attempt on the summit of Mount Everest in 1936. After exceptionally rancorous arguments involving the Mount Everest Committee in London, Eric Shipton was appointed leader following his successful trekking style of expedition to the Nanda Devi region in India in 1934.

Leslie Vickery Bryant, known as Dan Bryant, was a New Zealand school teacher and a mountain climber. He was a member of the 1935 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition, which was a preliminary to the full expedition of 1936 that attempted the summit. However in 1935 Bryant did not acclimatise well to altitude above 23,000 feet (7,000 m), and so was not included in the party for 1936. He was a very accomplished ice climber, and was well-liked on expeditions. These two factors led, indirectly, to his compatriot Edmund Hillary becoming a member of the successful 1953 British Mount Everest expedition.

Led by Bill Tilman, the 1938 British Mount Everest expedition was a low-key, low-cost expedition which was unlucky in encountering a very early monsoon. The weather conditions defeated the attempts to reach the summit. The North Col was climbed for the first time from the west and an altitude of 27,200 feet (8,300 m) was reached on the North Ridge.

The Shipton–Tilman Nanda Devi expeditions took place in the 1930s. Nanda Devi is a Himalayan mountain in what was then the Garhwal District in northern India, just west of Nepal, and at one time it was thought to be the highest mountain in the world.

Ang Tharkay was a Nepalese mountain climber and explorer who acted as sherpa and later sirdar for many Himalayan expeditions. He was "beyond question the outstanding sherpa of his era" and he introduced Tenzing Norgay to the world of mountaineering.

After World War II, with Tibet closing its borders and Nepal becoming considerably more open, Mount Everest reconnaissance from Nepal became possible for the first time culminating in the successful ascent of 1953. In 1950 there was a highly informal trek to what was to become Everest Base Camp and photographs were taken of a possible route ahead. Next year the 1951 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition reconnoitred various possible routes to Mount Everest from the south and the only one they considered feasible was the one via the Khumbu Icefall, Western Cwm and South Col. In 1952, while the Swiss were making an attempt on the summit that nearly succeeded; the 1952 British Cho Oyu expedition practised high-altitude Himalayan techniques on Cho Oyu, nearby to the west.

The 1951 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition ran between 27 August 1951 and 21 November 1951 with Eric Shipton as leader.

Pasang Kikuli (1911–1939) was a Nepalese mountain climber and explorer who acted as sherpa and later sirdar for many Himalayan expeditions. He died on the 1939 American Karakoram expedition to K2, attempting to rescue a stranded climber.