Related Research Articles

Luís Carlos Prestes was a Brazilian revolutionary and politician who served as the general-secretary of the Brazilian Communist Party from 1943 to 1980 and a senator for the Federal District from 1946 to 1948. One of the leading communists in Brazil, Prestes has been regarded by many as one of Brazil's most charismatic yet tragic figures for his leadership of the 1924 tenente revolt and his subsequent work with the Brazilian communist movement. The 1924 expedition earned Prestes the nickname The Knight of Hope.

Student activism or campus activism is work by students to cause political, environmental, economic, or social change. In addition to education, student groups often play central roles in democratization and winning civil rights.

The Fourth Brazilian Republic, also known as the "Populist Republic" or as the "Republic of 46", is the period of Brazilian history between 1946 and 1964. It was marked by political instability and the military's pressure on civilian politicians which ended with the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état and the establishment of the Brazilian military dictatorship.

The military dictatorship in Brazil occasionally referred to as the Fifth Brazilian Republic, was a governmental structure established on 1 April 1964, after a coup d'état by the Brazilian Armed Forces, with support from the United States government, against President João Goulart. The Brazilian dictatorship lasted for 21 years, until 15 March 1985. The coup was planned and executed by the most senior commanders of the Brazilian Army and received the support of almost all high-ranking members of the military, along with conservative elements in society, like the Catholic Church and anti-communist civil movements among the Brazilian middle and upper classes. The military regime, particularly after the Institutional Act Number Five in 1968, practiced extensive censorship and committed gross human rights abuses, including institutionalized torture and extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances. Despite initial pledges to the contrary, the military regime enacted in 1967 a new, restrictive Constitution, and stifled freedom of speech and political opposition. The regime adopted nationalism, economic development, and anti-communism as its guidelines.

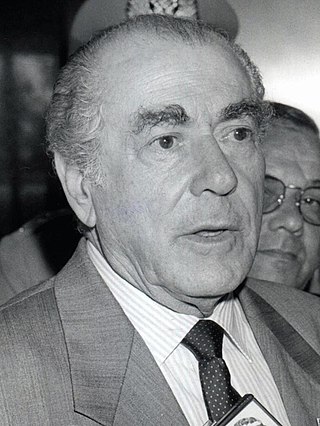

Leonel de Moura Brizola was a Brazilian politician. Launched into politics by Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas in the 1930–1950s, Brizola was the only politician to serve as elected governor of two Brazilian states. An engineer by training, Brizola organized the youth wing of the Brazilian Labour Party and served as state representative for Rio Grande do Sul and mayor of its capital, Porto Alegre. In 1958 he was elected governor and subsequently played a major role in thwarting a first coup attempt by sectors of the armed forces in 1961, who wished to stop João Goulart from assuming the presidency, under allegations of communist ties. Three years later, facing the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état that went on to install the Brazilian military dictatorship, Brizola again wanted the democratic forces to resist, but Goulart did not want to risk the possibility of civil war, and Brizola was exiled in Uruguay.

Bijan Jazani 9 January 1938, Tehran – 19 April 1975 was an Iranian political activist and a significant figure among modern Iranian Socialist intellectuals. A Marxist theorist, Jazani was one of the founders of the Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas.

Brazilian Integralist Action was an integralist/fascist political party in Brazil. It was based upon the ideology of Brazilian Integralism as developed by its leader Plínio Salgado. Brazilian Integralism supported a revival of spirituality in Brazil in the form of Brazilian nationalism to form a shared identity between Brazilians. It denounced materialism, liberalism, and Marxism. It was violently opposed to the Brazilian Communist Party and competed with the Communists for the working class vote.

The Armed Forces Movement was an organization of lower-ranking officers in the Portuguese Armed Forces. It was responsible for instigating the Carnation Revolution of 1974, a military coup in Lisbon that ended Portugal's corporatist New State regime and the Portuguese Colonial War, which led to the independence of Portugal's overseas territories in Africa. The MFA instituted the National Salvation Junta as the provisional national government 1974 to 1976, following a communiqué of its president, António de Spínola, at 1:30 a.m. on 26 April 1974.

The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, which were predominantly characterized by popular rebellions against state militaries and bureaucracies.

The 1964 Brazilian coup d'état was the overthrow of the Brazilian president João Goulart by a military coup from March 31 to April 1, 1964, ending the Fourth Brazilian Republic (1946–1964) and initiating the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985). The coup took the form of a military rebellion, the declaration of vacancy in the presidency by the National Congress on April 2, the formation of a military junta and the exile of the president on April 4. In his place, Ranieri Mazzilli, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, took over until the election by Congress of general Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, one of the main leaders of the coup.

Argentine Revolution was the name given by its leaders to a military coup d'état which head the government of Argentina in June 1966 and began a period of military dictatorship by a junta from then until 1973.

The Revolutionary Communist Party is an anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninist communist party in Brazil with strong Stalinist tendencies. Originally formed in 1966 after a split with the Communist Party of Brazil, it later merged with the October 8th Revolutionary Movement in 1981, from which it split in 1995. It is a member of the International Conference of Marxist-Leninist Parties and Organizations (ICMLPO), an organization of anti-revisionist and Hoxhaist parties. As the party is not registered in Brazil's Superior Electoral Court, its members cannot run for public office.

The history of the socialist movement in Brazil is generally thought to trace back to the first half of the 19th century. There are documents evidencing the diffusion of socialist ideas since then, but these were individual initiatives with no ability to form groups with actual political activism.

Torture Never Again is a Brazilian human rights organization, founded by Cecília Coimbra, a victim of Brazilian military torturers.

The Committee for Peasant Unity was an indigenous Guatemalan labor organization. It has been described as the most potent peasant organization since the 1944–1954 Guatemalan Revolution.

Student activism in the Philippines from 1965 to 1972 played a key role in the events which led to Ferdinand Marcos' declaration of Martial Law in 1972, and the Marcos regime's eventual downfall during the events of the People Power Revolution of 1986.

Brazil–United States relations during the João Goulart government (1961–1964) gradually deteriorated, culminating in American support for the ousting of the Brazilian president in the 1964 coup d'état in Brazil. Although the dynamics of the crisis were primarily Brazilian, American actions progressively increased the chances of the occurrence and success of a rebellion against the government. Historians differ on the inevitability of a clash between the Goulart and John F. Kennedy/Lyndon B. Johnson administrations, the relative importance of the attrition points, and the timing of when the U.S. government decided to support the Brazilian's deposition - earlier, as in 1962, or later, only in 1963.

On October 4, 1963, the President of Brazil João Goulart sent to the National Congress a request for a state of exception for 30 days throughout the national territory. Citing as justification the crisis and the threat of internal disturbances, it was based on the resistance of Congress to approve the reforms desired by the Executive, as well as the need to assert itself before the opposition. Its immediate antecedent was an interview by Carlos Lacerda, governor of Guanabara, to the American newspaper Los Angeles Times. Lacerda spoke explicitly of the possibility of Goulart being deposed by the military. The Ministers of War, Navy and Air Force, outraged, wanted forceful action against the governor, who was a right-wing oppositionist. The state of exception would possibly be accompanied by federal intervention in some states, and is associated with a military plan to arrest Lacerda and an operation in Pernambuco, governed by leftist Miguel Arraes, who was against the measure. The proposal was rejected by both the right and the left, who felt they could also be targeted by the exceptional powers. Without support, the President withdrew the proposal on October 7, and his political position was weakened.

The Sailors' Revolt was a conflict between the Brazilian Navy authorities and the Association of Sailors and Marines of Brazil (AMFNB) from March 25 to 27, 1964, taking place in Rio de Janeiro at the Sindicato dos Metalúrgicos, Arsenal de Marinha, and Armada ships. Its outcome, negotiated by João Goulart's government, outraged the perpetrators of the coup d'état a few days later, and was thus one of its immediate antecedents.

Brazil's economic policy can be broadly defined by the Brazilian government's choice of fiscal policies, and the Brazilian Central Bank’s choice of monetary policies. Throughout the history of the country, economic policy has changed depending on administration in power, producing different results.

References

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Duram: Duke University Press. p. 28.

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Duram: Duke University Press. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Rise of Student Movements | Brazil: Five Centuries of Change". library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Duram: Duke University Press. p. 64.

- ↑ Langland, Victoria (2013). Speaking of Flowers. Duram: Duke University Press. pp. 81–87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gould, Jeffery (April 2009). "Solidarity under Siege: The Latin American Left, 1968". The American Historical Review. 114 (2): 357–360. doi: 10.1086/ahr.114.2.348 .

- 1 2 Lowy, Michael (1979). "Students and Class Struggle in Brazil". Latin American Perspectives. 6 (4): 101–102. doi:10.1177/0094582X7900600409. JSTOR 2633236. S2CID 144029174.