The Red River, also called the Red River of the North to differentiate it from the Red River in the south of the continent, is a river in the north-central United States and central Canada. Originating at the confluence of the Bois de Sioux and Otter Tail rivers between the U.S. states of Minnesota and North Dakota, it flows northward through the Red River Valley, forming most of the border of Minnesota and North Dakota and continuing into Manitoba. It empties into Lake Winnipeg, whose waters join the Nelson River and ultimately flow into Hudson Bay.

The Red River Floodway is an artificial flood control waterway in Western Canada. It is a 47 km (29 mi) long channel which, during flood periods, takes part of the Red River's flow around the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba to the east and discharges it back into the Red River below the dam at Lockport. It can carry floodwater at a rate of up to 140,000 cubic feet per second (4,000 m3/s), expanded in the 2000s from its original channel capacity of 90,000 cubic feet per second (2,500 m3/s).

The Grand Forks Herald is a daily broadsheet newspaper, established in 1879, published in Grand Forks, North Dakota, United States. It is the primary daily paper for northeast North Dakota and northwest Minnesota. Its average daily circulation is approximately 7,500, in the city of Grand Forks plus about 7,500 more to the surrounding communities. Total circulation includes digital subscribers. It has the second largest circulation in the state of North Dakota.

The Red River Valley is a region in central North America that is drained by the Red River of the North; it is part of both Canada and the United States. Forming the border between Minnesota and North Dakota when these territories were admitted as states in the United States, this fertile valley has been important to the economies of these states and to Manitoba, Canada.

WDAZ-TV is a television station licensed to Devils Lake, North Dakota, United States, serving the Grand Forks area as an affiliate of ABC. It is owned by the Forum Communications Company, which also owns the Grand Forks Herald. WDAZ-TV's news bureau and advertising sales office are located on South Washington Street in Grand Forks, and its transmitter is located near Dahlen, North Dakota. Despite Devils Lake being WDAZ-TV's city of license, the station maintains no physical presence there.

The Sheyenne River is one of the major tributaries of the Red River of the North, meandering 591 miles (951 km) across eastern North Dakota, United States.

The Greater Grand Forks Greenway is a huge greenway bordering the Red River and Red Lake River in the twin cities of Grand Forks, North Dakota and East Grand Forks, Minnesota. At 2,200 acres (9 km2), the Greenway is more than twice the size of New York City's Central Park. It has an extensive, 20-mile (32 km) system of bike paths, which are used by bikers, walkers, joggers, and rollerbladers. In 2007, the system was designated as a National Recreation Trail by the National Park Service.

KFGO is an AM radio station in the United States. Licensed to Fargo, North Dakota, KFGO broadcasts a news and talk radio format serving the Fargo-Moorhead metropolitan area, branded "The Mighty 790, 94.1, and 104.7". The station is currently owned by Midwest Communications Inc. All the offices and studios are located at 1020 S. 25th Street in Fargo, while its transmitter array is located north of Oxbow. It is an affiliate of the CBS Radio Network. KFGO is simulcast on KFGO-FM and translator K231CV.

The 1950 Red River flood was a devastating flood that took place along the Red River in The Dakotas and Manitoba from April 15 to June 12, 1950. Damage was particularly severe in the city of Winnipeg and its environs, which were inundated on May 5, also known as Black Friday to some residents.

The Portage Diversion is a water control structure on the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, Canada. The project was made as part of a larger attempt to prevent flooding in the Red River Valley. The Portage Diversion consists of two separate gates which divert some of the flow of water in the Assiniboine River to a 29 km long diversion channel that empties into Lake Manitoba near Delta Beach. This helps prevent flooding on the Assiniboine down river from the diversion, including in Winnipeg, where the Assiniboine River meets the Red River.

The recorded history of Grand Forks in the U.S. state of North Dakota, began with the trade between Native Americans and French fur trappers during the 19th century. About 60 buildings or other historic sites in Grand Forks survive and are recognized among the National Register of Historic Places listings in Grand Forks County.

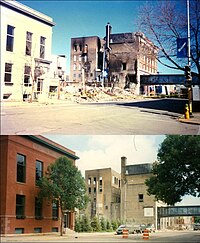

The Red River flood of 1997 in the United States was a major flood that occurred in April 1997, along the Red River of the North in North Dakota and Minnesota. The flood reached throughout the Red River Valley, affecting the cities of Fargo, Moorhead, and Winnipeg, while Grand Forks and East Grand Forks received the most damage, where floodwaters reached over 3 miles (5 km) inland, inundating virtually everything in the twin communities. Total damages for the Red River region were US$3.5 billion.

The 2009 Red River flood along the Red River of the North in North Dakota and Minnesota in the United States and Manitoba in Canada brought record flood levels to the Fargo-Moorhead area. The flood was a result of saturated and frozen ground, spring snowmelt exacerbated by additional rain and snow storms, and virtually flat terrain. Communities along the Red River prepared for more than a week as the U.S. National Weather Service continuously updated the predictions for the city of Fargo, North Dakota, with an increasingly higher projected river crest. Originally predicted to reach a level of near 43 feet (13 m) at Fargo by March 29, the river in fact crested at 40.84 feet (12.45 m) at 12:15 a.m. March 28, and started a slow decline. The river continued to rise to the north as the crest moved downstream.

The US State of North Dakota experienced significant flooding in its major river basins in 2009, following abnormally heavy winter snows atop saturated and frozen ground.

The Red River floods refer to the various flooding events in recent history of the Red River of the North, which forms the border between North Dakota and Minnesota and flows north, into Manitoba.

The 2011 Red River flood took place along the Red River of the North in Manitoba in Canada and North Dakota and Minnesota in the United States beginning in April 2011. The flood was, in part, due to high moisture levels in the soil from the previous year, which meant that further accumulation would threaten the flood-prone region. Flood predictors in Winnipeg were worried that a dual crest of both the Assiniboine River and the Red might crest at the city at the same time. Beginning around April 8, 50 homes were evacuated and two more were flooded after an ice jam in St. Andrews, Manitoba caused the river to flood over its banks.

The 2011 Assiniboine River flood was caused by above average precipitation in Western Manitoba and Saskatchewan. This was a 1 in 300 year flood that affected much of Western Manitoba. The flooding in Manitoba was expected to mostly involve the 2011 Red River Flood but instead the more severe flooding was found on the Assiniboine in the west.

The 2011 Souris/Mouse River flood in Canada and the United States occurred in June and was greater than a hundred-year flooding event for the river. The US Army Corps of Engineers estimated the flood to have a recurrence interval of two to five centuries.

The Northern Great Plains History Conference is an annual conference of history professors, graduate students, historical society experts, and other scholars interested in the history of the Great Plains states of the American Midwest. The Conference features scholarly papers by academics and advanced students on a variety of topics, especially in social history and military history, as well as regional topics regarding the Great Plains.

The Fargo-Moorhead (FM) Area Diversion project, officially known as the Fargo-Moorhead Metropolitan Area Diversion Flood Risk Management Project, is a large, regional flood control infrastructure project on the Red River of the North, which forms the border between North Dakota and Minnesota and flows north to Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba, Canada.