World War I

The regiment was organized 31 August 1917 at Camp Jackson, South Carolina as the 1st Provisional Infantry Regiment, primarily or entirely from draftees. The regiment was initially commanded by Colonel Perry L. Miles. Due to a labor shortage for moving the cotton crop, arrival of draftees was delayed until October, and the regiment did not complete organization until 20 November 1917. On 1 December 1917, the regiment was redesignated as the 371st Infantry Regiment and assigned to the 93rd Division (Provisional). [1] [3] However, the division was never fully organized and its headquarters elements were demobilized in May 1918. [4]

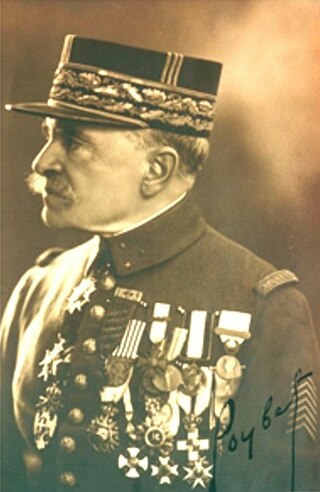

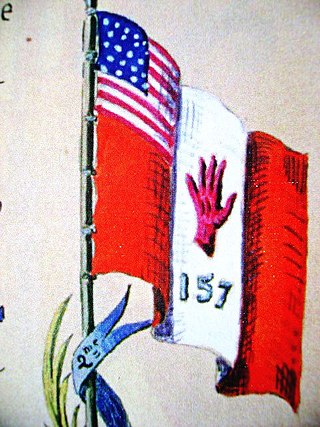

The regiment moved to France in April 1918. On arrival in France, the unit was transferred into the French command, so most of its decorations are French rather than American. The 371st Infantry was seconded, along with the 372nd Infantry Regiment, to the 157th Infantry Division of the French Army, called the "Red Hand Division". [3] Under the command of General Mariano Goybet, the division was in need of reinforcements.

Emmet J. Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War provides a summary of when the men were fighting with gallantry on the Western Front in the Champagne region of France for victory: [3]

"The 371st remained in line for over three months, holding first the Avocourt and later the Verrières subsectors (northwest of Verdun). The regiment, with its division, was then taken out of line and thrown into the great September offensive in the Champagne. It took Côte 188 (Hill 188), Bussy Ferme, Ardeuil, Montfauxelles, and Trieres Ferme near Monthois, and captured a number of prisoners, 47 machine guns, 8 trench engines (possibly minenwerfers), 3 field pieces (77 mm guns), a munition depot, a number of railroad cars, and enormous quantities of lumber, hay, and other supplies. It shot down three German airplanes by rifle and machine-gun fire during the advance." [3]

"During the fighting between September 28 and October 6, 1918, its losses—which were mostly in the first three days—were 1,065 out of 2,384 actually engaged (total killed, wounded, prisoners, and missing). ("American Armies" gives 882 casualties for the same period, but only includes casualties "while in line".) [5] The regiment was the apex of the attacking salient in this great battle. The percentage of both dead and wounded among the officers was rather greater than among the enlisted men. Realizing their great responsibilities, the wounded officers continued to lead their men until they dropped from exhaustion and lack of blood. The men were devoted to their, leaders and as a result stood up against—a most grueling fire, bringing the regiment its well deserved fame." [3]

Much of the fighting took place near Ardeuil and Sechault. [6]

The 371st was awarded the French Croix de Guerre as a unit award. Following a review of Medal of Honor recommendations, one enlisted man, Freddie Stowers, received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1991 for actions in the assault on Côte 188. [7] During the war, one officer received the French Légion d'Honneur, 22 officers and men received the Distinguished Service Cross (United States), and 123 officers and men received the French Croix de Guerre. [3]

The regiment returned to the US in February 1919 on the transport USS Leviathan, demobilizing at the end of the month at Camp Jackson, SC. [1] [3]

Medal of Honor recipient

Corporal Freddie Stowers is the only soldier from the 371st Infantry who was awarded the Medal of Honor. His recommendation for the medal was "not processed" (or perhaps lost) by higher headquarters at the time; the medal was eventually awarded in 1991 based on an Army review of African American Medal of Honor recommendations requested by Congress. [7]

Citation for the men of 157th Division

The following order was issued to the 157th Division following the campaign in the Champagne region: [8]

P. C. October 8, 1918.

"157th Division.

"Staff.

General Order No. 234

"In transmitting to you with legitimate pride the thanks and congratulations of the General Garnier-Duplessis, allow me, my dear friends of all ranks, Americans and French, to thank you from the bottom of my heart as a chief and a soldier for the expression of gratitude for the glory which you have lent our good 157th Division. I had full confidence in you but you have surpassed my hopes.

"During these nine days of hard fighting you have progressed nine kilometers through powerful organized defenses, taken nearly 600 prisoners, 15 guns of different calibres, 20 minenwerfers, and nearly 150 machine guns, secured an enormous amount of engineering material, an important supply of artillery ammunition, brought down by your fire three enemy aeroplanes.

"THE RED HAND", sign of the Division, thanks to you, became a bloody hand which took the Boche by the throat and made him cry for mercy. You have well avenged our glorious dead.

Signed General Goybet

World War II

The 371st was activated on 15 October 1942 at Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Arkansas and assigned to the 92nd Infantry Division (Colored). [2]

The unit moved to Fort Huachuca, Arizona 8 May 1943. Later, the 371st staged for overseas movement at Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia 12 September 1944, departing Hampton Roads 22 September 1944, arriving in Livorno, Italy 18 October 1944. The regiment entered the line 31 October 1944, joining other elements of the 92nd Infantry Division already in place for combat in the Italian Campaign along the Gothic Line. [2]

By late December 1944 the 92nd Infantry Division occupied part of the Serchio Valley. A German attack on 26–27 December 1944 caused the division to retreat; the Germans were stopped by the 8th Indian Infantry Division. In February 1945 two other regiments of the 92nd recovered much of the lost ground. However, the division experienced mixed results before mid-February, gaining a bridgehead over the Cinquale Canal but losing ground east of the river. On 11 February this bridgehead was withdrawn and the division broke off attacks. [2]

From 1 March to 3 April 1945 the 92nd Infantry Division was reorganized. Its commander, Major General Edward Almond, repeatedly expressed the (then widely held) opinion that blacks made poor soldiers, and reorganized the division with most of its infantry replaced by other units. [12] The 371st, along with the 365th, another regiment of the division, was withdrawn from the front line and designated a "security" regiment, presumably for military police duties. These regiments were replaced by the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 473rd Infantry Regiment, the latter a white regiment recently formed by reorganizing three anti-aircraft battalions. Although not formally relieved from the division, the 371st and 365th remained on rear area duties until returned to the US for inactivation in November 1945. [2] [13]

In August 1945, at the cessation of hostilities with Japan, the 371st was at Torre del Lago, less 3rd Battalion at Aversa and Co. M at Secondigliano. [2]

On 24 November 1945, the 371st arrived at the New York Port of Embarkation and was inactivated at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey on the 28th. [2]