Related Research Articles

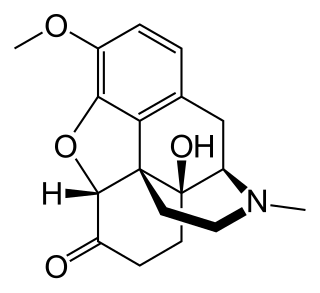

Oxycodone, sold under various brand names such as Roxicodone and OxyContin, is a semi-synthetic opioid used medically for treatment of moderate to severe pain. It is highly addictive and is a commonly abused drug. It is usually taken by mouth, and is available in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations. Onset of pain relief typically begins within fifteen minutes and lasts for up to six hours with the immediate-release formulation. In the United Kingdom, it is available by injection. Combination products are also available with paracetamol (acetaminophen), ibuprofen, naloxone, naltrexone, and aspirin.

Opioids are a class of drugs that derive from, or mimic, natural substances found in the opium poppy plant. Opioids work in the brain to produce a variety of effects, including pain relief. As a class of substances, they act on opioid receptors to produce morphine-like effects.

Oxycodone/paracetamol, sold under the brand name Percocet among others, is a fixed-dose combination of the opioid oxycodone with paracetamol (acetaminophen), used to treat moderate to severe pain.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a substance use disorder characterized by cravings for opioids, continued use despite physical and/or psychological deterioration, increased tolerance with use, and withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing opioids. Opioid withdrawal symptoms include nausea, muscle aches, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, agitation, and a low mood. Addiction and dependence are important components of opioid use disorder.

Buprenorphine, sold under the brand name Subutex among others, is an opioid used to treat opioid use disorder, acute pain, and chronic pain. It can be used under the tongue (sublingual), in the cheek (buccal), by injection, as a skin patch (transdermal), or as an implant. For opioid use disorder, the patient must have moderate opioid withdrawal symptoms before buprenorphine can be administered under direct observation of a health-care provider.

Sally L. Satel is an American psychiatrist based in Washington, D.C. She is a lecturer at Yale University School of Medicine, a visiting professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and an author.

A methadone clinic is a medical facility where medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are dispensed-—historically and most commonly methadone, although buprenorphine is also increasingly prescribed. Medically assisted drug therapy treatment is indicated in patients who are opioid-dependent or have a history of opioid dependence. Methadone is a schedule II (USA) opioid analgesic, that is also prescribed for pain management. It is a long-acting opioid that can delay the opioid withdrawal symptoms that patients experience from taking short-acting opioids, like heroin, and allow time for withdrawal management. In the United States, by law, patients must receive methadone under the supervision of a physician, and dispensed through an Opioid Treatment Program (OTP) certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and registered with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Purdue Pharma L.P., formerly the Purdue Frederick Company (1892–2019), was an American privately held pharmaceutical company founded by John Purdue Gray. It was sold to Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler in 1952, and then owned principally by the Sackler family and their descendants.

Raymond Sackler was an American physician and businessman. He acquired Purdue Pharma together with his brothers Arthur M. Sackler and Mortimer Sackler. Purdue Pharma is the developer of OxyContin, the drug at the center of the opioid epidemic in the United States.

The Woozle effect, also known as evidence by citation, occurs when a source is widely cited for a claim it does not adequately support, giving said claim undeserved credibility. If results are not replicated and no one notices that a key claim was never well-supported in its original publication, faulty assumptions may affect further research.

In the United States, the opioid epidemic is an extensive, ongoing overuse of opioid medications, both from medical prescriptions and illegal sources. The epidemic began in the United States in the late 1990s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), when opioids were increasingly prescribed for pain management, resulting in a rise in overall opioid use throughout subsequent years. The great majority of Americans who use prescription opioids do not believe that they are misusing them.

David Juurlink is a Canadian pharmacologist and internist. He is head of the Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology division at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, Ontario, as well as a medical toxicologist at the Ontario Poison Centre and a scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. He is known for researching adverse effects caused by drug interactions, with some of this research funded by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. He has been very critical of his fellow physicians' regular prescribing of dangerous opioids like Tramadol and fentanyl. In June 2017, he published a letter analyzing citations to "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics", a 1980 letter in The New England Journal of Medicine that has often been cited to claim that opioids like OxyContin are rarely addictive.

Hershel M. Jick was an American medical researcher and associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, where he was the director of the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program.

MedPage Today is a medical news-focused site owned by Ziff-Davis, LLC. It is based in New York City, and is geared primarily toward medical and health professionals.

Richard Stephen Sackler is an American billionaire businessman and physician who was the chairman and president of Purdue Pharma, a former company best known as the developer of OxyContin, whose connection to the opioid epidemic in the United States was the subject of multiple lawsuits and fines, and that filed for bankruptcy in 2019. It has been claimed that Richard Sackler's Purdue is among ”the worst drug dealers in history” and the Sackler family have been described as the "most evil family in America". The company's downfall was the subject of the 2021 Hulu series Dopesick and the 2023 Netflix series Painkiller.

Massachusetts v. Purdue is a lawsuit filed on August 14, 2018, suing the Stamford, Connecticut-based company Purdue Pharma LP, which created and manufactures OxyContin, "one of the most widely used and prescribed opioid drugs on the market", and Purdue's owners, the Sacklers accusing them of "widespread fraud and deception in the marketing of opioids, and contributing to the opioid crisis, the nationwide epidemic that has killed thousands." Purdue denied the allegations.

The opioid epidemic, also referred to as the opioid crisis, is the rapid increase in the overuse, misuse/abuse, and overdose deaths attributed either in part or in whole to the class of drugs called opiates/opioids since the 1990s. It includes the significant medical, social, psychological, demographic and economic consequences of the medical, non-medical, and recreational abuse of these medications.

The timeline of the opioid epidemic includes selected events related to the origins of Stamford, Connecticut-based Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family, the development and marketing of oxycodone, selected FDA activities related to the abuse and misuse of opioids, the recognition of the opioid epidemic, the social impact of the crisis, lawsuits against Purdue and the Sackler family.

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) is a treatment in which prescribed opioid agonists are given to patients who live with Opioid use disorder (OUD). In the case of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), methadone is used to treat dependence on heroin or other opioids, and is administered on an ongoing basis.

Curtis Wright IV is an American former government official known for his role in the Food and Drug Administration's approval of OxyContin for Purdue Pharma in 1995, followed by his subsequent employment by the company, which led to portrayals in films and reports in nonfiction books, magazines, and news media outlets of his alleged role as one of the key figures in the current opioid epidemic in the United States. Wright was implicated in a criminal conspiracy outlined in a 2006 United States Department of Justice review document that was first made public in Purdue Pharma's 2019 bankruptcy proceedings. Although that case was settled in a 2007 plea agreement deal, members of United States Congress have requested the full 2006 documentation from the Department of Justice with the goal of opening a new case based upon the evidence then gathered. Parts of Wright's sworn depositions in 2003 and 2018 have internal contradictions and differ from documentary evidence described the 2003–2006 U.S. Federal Government investigation into Purdue Pharma.

References

- ↑ Porter, J.; Jick, H. (10 January 1980). "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics". New England Journal of Medicine. 302 (2): 123. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001103020221 . PMID 7350425.

- 1 2 Jacobs, Harrison (26 May 2016). "This one-paragraph letter may have launched the opioid epidemic". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Kounang, Nadia (1 June 2017). "One short letter's huge impact on the opioid epidemic". CNN. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Hawkins, Derek (2 June 2017). "How a short letter in a prestigious journal contributed to the opioid crisis". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Meier, Barry (25 November 2003). "The Delicate Balance Of Pain and Addiction". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Kaplan, Karen (31 May 2017). "How a 5-sentence letter helped fuel the opioid addiction crisis". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Leung, Pamela T.M.; Macdonald, Erin M.; Stanbrook, Matthew B.; Dhalla, Irfan A.; Juurlink, David N. (June 2017). "A 1980 Letter on the Risk of Opioid Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (22): 2194–2195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1700150 . PMID 28564561.

- ↑ Zhang, Sarah (2 June 2017). "The One-Paragraph Letter From 1980 That Fueled the Opioid Crisis". The Atlantic. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Van Zee, Art (February 2009). "The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (2): 221–227. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714. PMC 2622774 . PMID 18799767.

- ↑ Engber, Daniel (11 June 2017). "Bad Footnotes Can Be Deadly". Slate. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "Opioid crisis: The letter that started it all". BBC News. 3 June 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Haney, Taylor (16 June 2017). "Doctor Who Wrote 1980 Letter On Painkillers Regrets That It Fed The Opioid Crisis". NPR. Retrieved 24 June 2017.