The sipahi were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk Turks and later by the Ottoman Empire. Sipahi units included the land grant–holding (timar) provincial timarli sipahi, which constituted most of the army, and the salaried regular kapikulu sipahi, or palace troops. However, the irregular light cavalry akıncı ("raiders") were not considered to be sipahi. The sipahi formed their own distinctive social classes and were rivals to the janissaries, the elite infantry corps of the sultans.

A sanjak was an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans also sometimes called the sanjak a liva from the name's calque in Arabic and Persian.

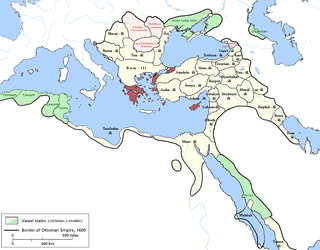

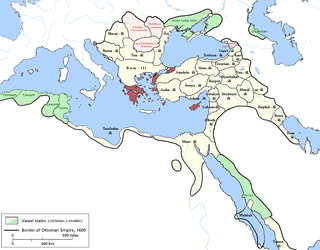

Eyalets, also known as beylerbeyliks or pashaliks, were the primary administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire.

The Eyalet of Cyprus was an eyalet (province) of the Ottoman Empire made up of the island of Cyprus, which was annexed into the Empire in 1571. The Ottomans changed the way they administered Cyprus multiple times. It was a sanjak (sub-province) of the Eyalet of the Archipelago from 1670 to 1703, and again from 1784 onwards; a fief of the Grand Vizier ; and again an eyalet for the short period from 1745 to 1748.

Sanjak-bey, sanjaq-bey or -beg was the title given in the Ottoman Empire to a bey appointed to the military and administrative command of a district, hence the equivalent Arabic title of amir liwa He was answerable to a superior wāli or another provincial governor. In a few cases the sanjak-bey was himself directly answerable to Istanbul.

Beylerbey was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Seljuks and the Ilkhanids to Safavid Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Initially designating a commander-in-chief, it eventually came to be held by senior provincial governors. In Ottoman usage, where the rank survived the longest, it designated the governors-general of some of the largest and most important provinces, although in later centuries it became devalued into a mere honorific title. The title is originally Turkic and its equivalents in Arabic were amir al-umara, and in Persian, mir-i miran.

A timar was a land grant by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, with an annual tax revenue of less than 20,000 akçes. The revenues produced from the land acted as compensation for military service. A holder of a timar was known as a timariot. If the revenues produced from the timar were from 20,000 to 100,000 akçes, the land grant was called a zeamet, and if they were above 100,000 akçes, the grant would be called a hass.

The Eyalet of Bosnia, was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based on the territory of the present-day state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Prior to the Great Turkish War, it had also included most of Slavonia, Lika, and Dalmatia in present-day Croatia. Its reported area in 1853 was 52,530 square kilometres (20,281 sq mi).

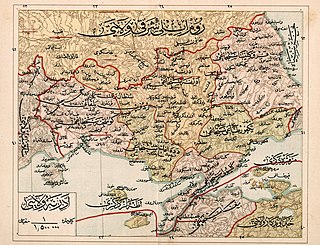

A vilayet, also known by various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement initiated by the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856. The Danube Vilayet had been specially formed in 1864 as an experiment under the leading reformer Midhat Pasha. The Vilayet Law expanded its use, but it was not until 1884 that it was applied to all of the empire's provinces. Writing for the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1911, Vincent Henry Penalver Caillard claimed that the reform had intended to provide the provinces with greater amounts of local self-government but in fact had the effect of centralizing more power with the sultan and local Muslims at the expense of other communities.

The Eyalet of Kefe or Caffa was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. The eyalet stretched across the northern coast of the Black Sea with the main sanjak being located in the southern coast of Crimea. The eyalet was under direct Ottoman rule, completely separate from the Khanate of Crimea. Its capital was at Kefe, the Turkish name for Caffa.

The eyalet of Rakka or Urfa was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. Its reported area in the 19th century was 24,062 square miles (62,320 km2).

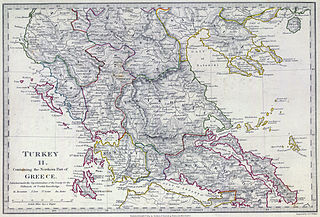

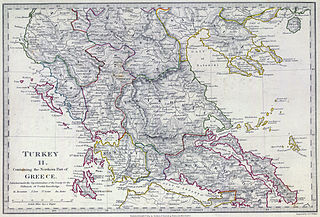

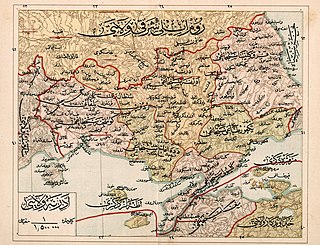

The Eyalet of Rumeli, or Eyalet ofRumelia, known as the Beylerbeylik of Rumeli until 1591, was a first-level province of the Ottoman Empire encompassing most of the Balkans ("Rumelia"). For most of its history, it was the largest and most important province of the Empire, containing key cities such as Edirne, Yanina (Ioannina), Sofia, Filibe (Plovdiv), Manastır/Monastir (Bitola), Üsküp (Skopje), and the major seaport of Selânik/Salonica (Thessaloniki). It was also among the oldest Ottoman eyalets, lasting more than 500 years with several territorial restructurings over the long course of its existence.

The Sanjak of Albania was a second-level administrative unit of the Ottoman Empire between 1415 and 1444. Its mandate included territories of modern central and southern Albania between Krujë to the Kalamas River in northwestern Greece.

The Sanjak of Üsküp was one of the sanjaks in the Ottoman Empire, with Üsküb as its administrative centre.

The Eyalet of the Islands of the White Sea was a first-level province (eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire. From its inception until the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th century, it was under the personal control of the Kapudan Pasha, the commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy.

The Sanjak of Ohri was one of the sanjaks of the Ottoman Empire established in 1395. Part of it was located on the territory of the Lordship of Prilep, a realm in Macedonia ruled by the Ottoman vassal Prince Marko until his death in the Battle of Rovine.

The Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, also known as the Sanjak of Jerusalem, was an Ottoman district with special administrative status established in 1872. The district encompassed Jerusalem as well as Hebron, Jaffa, Gaza and Beersheba. During the late Ottoman period, the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem was commonly referred to as Palestine; a very late Ottoman document describes Palestine as including the Sanjak of Nablus and Sanjak of Akka (Acre) as well, more in line with European usage. It was the 7th most heavily populated region of the Ottoman Empire's 36 provinces.

The Sanjak of Tirhala or Trikala was second-level Ottoman province encompassing the region of Thessaly. Its name derives from the Turkish version of the name of the town of Trikala. It was established after the conquest of Thessaly by the Ottomans led by Turahan Bey, a process which began at the end of the 14th century and ended in the mid-15th century.

The Sanjak of Gelibolu or Gallipoli was a second-level Ottoman province encompassing the Gallipoli Peninsula and a portion of southern Thrace. Gelibolu was the first Ottoman province in Europe, and for over a century the main base of the Ottoman Navy. Thereafter, and until the 18th century, it served as the seat of the Kapudan Pasha and capital of the Eyalet of the Archipelago.

The 1864 Vilayet Law, also known as the Provincial Reform Law, was introduced during the Tanzimat era of the late Ottoman Empire. This era of administration was marked by reform movements, with provincial movements led largely by Midhat Pasha, a key player in the Vilayet Law itself. The Vilayet Law reorganized the provinces within the empire, replacing the medieval eyalet system.