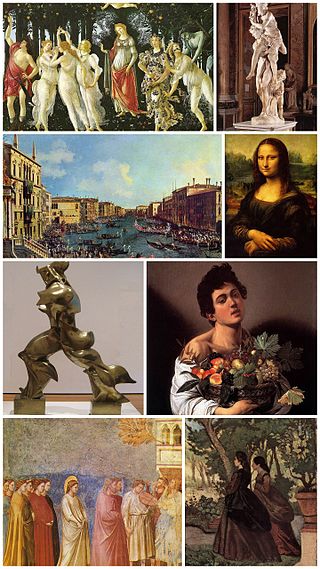

Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures included the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and according to its doctrine, aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past. Important Futurist works included Marinetti's 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises (1913).

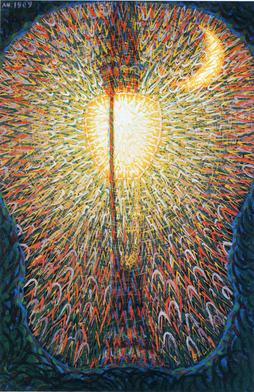

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter, art teacher and poet best known as a key proponent of Futurism. In his paintings, he depicted light, movement and speed. He was concerned with expressing movement in his works, but unlike other leading futurists he was not interested in machines or violence with his works tending towards the witty and whimsical.

Italian futurist cinema was the oldest movement of European avant-garde cinema. Italian futurism, an artistic and social movement, impacted the Italian film industry from 1916 to 1919. It influenced Russian Futurist cinema and German Expressionist cinema. Its cultural importance was considerable and influenced all subsequent avant-gardes, as well as some authors of narrative cinema; its echo expands to the dreamlike visions of some films by Alfred Hitchcock.

Fortunato Depero was an Italian futurist painter, writer, sculptor, and graphic designer.

Events from the year 1929 in art.

Futurist architecture is an early-20th century form of architecture born in ( ), characterized by long dynamic lines, suggesting speed, motion, urgency and lyricism: it was a part of Futurism, an artistic movement founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who produced its first manifesto, the Manifesto of Futurism, in 1909. The movement attracted not only poets, musicians, and artists but also a number of architects. A cult of the Machine Age and even a glorification of war and violence were among the themes of the Futurists - several prominent futurists were killed after volunteering to fight in World War I. The latter group included the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, who, though building little, translated the futurist vision into an urban form.

Franco Casavola was a Futurist composer and theorist. He is noted as one of the authors of the Le Sintesi Visive della Musica, a manifesto that proposed the intrinsic visual counterparts of music.

Gerardo Dottori was an Italian Futurist painter. He signed the Futurist Manifesto of Aeropainting in 1929. He was associated with the city of Perugia most of his life, living in Milan for six months as a student and in Rome from 1926-39. Dottori's' principal output was the representation of landscapes and visions of Umbria, mostly viewed from a great height. Among the most famous of these are Umbrian Spring and Fire in the City, both from the early 1920s; this last one is now housed in the Museo civico di Palazzo della Penna in Perugia, with many of Dottori's other works. His work was part of the art competitions at the 1932 Summer Olympics and the 1936 Summer Olympics.

Tullio Crali was a Dalmatian Italian artist associated with Futurism. A self-taught painter, he was a late adherent to the movement, not joining until 1929. He is noted for realistic paintings that combine "speed, aerial mechanisation and the mechanics of aerial warfare", though in a long career he painted in other styles as well.

Enrico Prampolini was an Italian Futurist painter, sculptor and scenographer. He assisted in the design of the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution and was active in Aeropainting.

Fillìa was the name adopted by Luigi Colombo, an Italian artist associated with the second generation of Futurism. Aside from painting, his works included interior design, architecture, furniture and decorative objects.

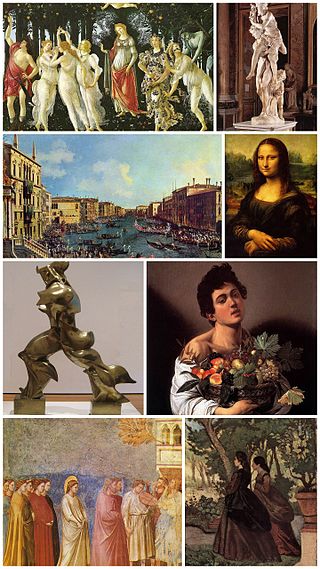

Italian Contemporary art refers to painting and sculpture in Italy from the early 20th century onwards.

Arnaldo Ginna, also known as Arnaldo Ginanni Corradini, was an Italian painter, sculptor and filmmaker. He was born in Ravenna, 7 May 1890; he died in Rome, 26 September 1982.

Benedetta Cappa was an Italian futurist artist who has had retrospectives at the Walker Art Center and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Her work fits within the second phase of Italian Futurism.

Alessandro Bruschetti was an Italian Futurist artist. The second most important Futurist painter from Umbria.

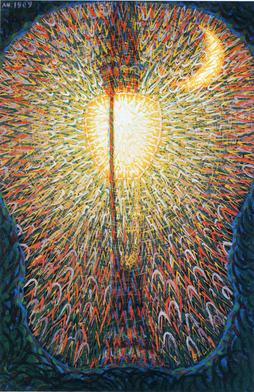

Street Light (also known as The Street Light: Study of Light and Street Lamp (Suffering of a Street Lamp)) (Italian: Lampada ad arco) is a painting by Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla, dated 1909, depicting an electric street lamp casting a glow that outshines the crescent moon. The painting was inspired by streetlights at the Piazza Termini in Rome.

Piero Dorazio was an Italian painter. His work was related to color field painting, lyrical abstraction and other forms of abstract art.

Růžena Zátková, also called Rougina Zatkova, was a painter and sculptor who has been regarded as the "only authentic Czech futurist." As a result of her Bohemian heritage and her decade-long residency in Rome, Růžena Zátková became an important artistic link between Russian and Italian Futurism. Zátková is considered one of the pioneers of kinetic art.

Ivo Pannaggi was an Italian painter and architect who was active in the Futurist movement and later associated with the Bauhaus.

Enrico Paulucci or Paulucci delle Roncole (1901–1999) was an Italian painter and scenic designer. He was one of the founding members of the Gruppo dei Sei.