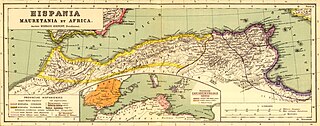

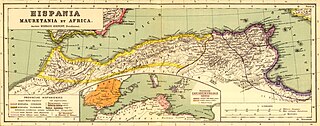

Mauretania is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants, of Berber ancestry, were known to the Romans as the Mauri and the Masaesyli.

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between the Massylii in the east and the Masaesyli in the west. During the Second Punic War, Masinissa, king of the Massylii, defeated Syphax of the Masaesyli to unify Numidia into the first Berber state in present-day Algeria. The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later alternated between being a Roman province and a Roman client state.

The history of North Africa during the period of classical antiquity can be divided roughly into the history of Egypt in the east, the history of ancient Libya in the middle and the history of Numidia and Mauretania in the West.

Tripolitania, historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province of Libya.

Thysdrus was a Carthaginian town and Roman colony near present-day El Djem, Tunisia. Under the Romans, it was the center of olive oil production in the provinces of Africa and Byzacena and was quite prosperous. The surviving amphitheater is a World Heritage Site.

Utica was an ancient Phoenician and Carthaginian city located near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean, between Carthage in the south and Hippo Diarrhytus in the north. It is traditionally considered to be the first colony to have been founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa. After Carthage's loss to Rome in the Punic Wars, Utica was an important Roman colony for seven centuries.

Hadrumetum, also known by many variant spellings and names, was a Phoenician colony that pre-dated Carthage. It subsequently became one of the most important cities in Roman Africa before Vandal and Umayyad conquerors left it ruined. In the early modern period, it was the village of Hammeim, now part of Sousse, Tunisia.

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in 591 and survived until the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the late 7th century. It was, along with the Exarchate of Ravenna, one of two exarchates established following the western reconquests under Emperor Justinian I to administer the territories more effectively.

Roman Africa may refer to the following areas of Northern Africa which were part of the Imperium Romanum and/or the Western/Byzantine successor empires :

Approximately 100 years after the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of the same name was built on the same land by the Romans in the period from 49 to 44 BC. By the 3rd century, Carthage had developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empire, with a population of several hundred thousand. It was the center of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the empire. Carthage briefly became the capital of a usurper, Domitius Alexander, in 308–311. Conquered by the Vandals in 439, Carthage served as the capital of the Vandal Kingdom for a century. Re-conquered by the Eastern Roman Empire in 533–534, it continued to serve as an Eastern Roman regional center, as the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa. The city was sacked and destroyed by Umayyad Arab forces after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire. A fortress on the site was garrisoned by Muslim forces until the Hafsid period, when it was captured by Crusaders during the Eighth Crusade. After the withdrawal of the Crusaders, the Hafsids decided to destroy the fortress to prevent any future use by a hostile power. Roman Carthage was used as a source of building materials for Kairouan and Tunis in the 8th century.

Āfrī was a Latin name for the inhabitants of Africa, referring in its widest sense to all the lands south of the Mediterranean. Latin speakers at first used āfer as an adjective, meaning "of Africa". As a substantive, it denoted a native of Āfrica; i.e., an African.

Leptis or Lepcis Parva was a Phoenician colony and Carthaginian and Roman port on Africa's Mediterranean coast, corresponding to the modern town Lemta, just south of Monastir, Tunisia. In antiquity, it was one of the wealthiest cities in the region.

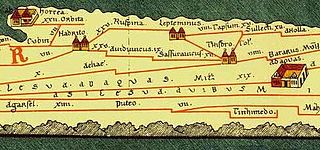

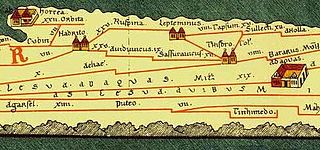

Abyla was the pre-Roman name of Ad Septem Fratres. Ad Septem Fratres, usually shortened to Septem or Septa, was a Roman colony in the province of Mauretania Tingitana and a Byzantine outpost in the exarchate of Africa. Its ruins are located within present-day Ceuta, an autonomous Spanish city in northwest Africa.

The Diocese of Africa was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, incorporating the provinces of North Africa, except Mauretania Tingitana. Its seat was at Carthage, and it was subordinate to the Praetorian prefecture of Italy.

The Praetorian Prefecture of Africa was an administrative division of the Byzantine Empire in the Maghreb. With its seat at Carthage, it was established after the reconquest of northwestern Africa from the Vandals in 533–534 by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. It continued to exist until 591, when it was replaced by the Exarchate of Africa.

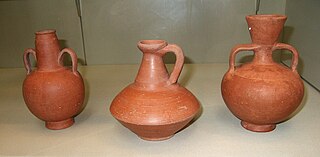

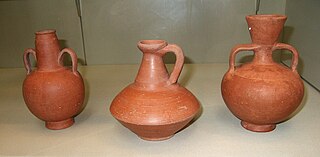

African red slip ware or Phoenician Red Slip ware, is a category of terra sigillata, or "fine" Phoenician pottery produced from the 7th century BC into the 7th century in the province of Africa Proconsularis, specifically that part roughly coinciding with the modern country of Tunisia and the Diocletianic provinces of Byzacena and Zeugitana. It is distinguished by a thick-orange red slip over a slightly granular fabric. Interior surfaces are completely covered, while the exterior can be only partially slipped, particularly on later examples.

Roman Tunisia initially included the early ancient Roman province of Africa, later renamed Africa Vetus. As the Roman empire expanded, the present Tunisia also included part of the province of Africa Nova.

The area of North Africa which has been known as Libya since 1911 was under Roman domination between 146 BC and 672 AD. The Latin name Libya at the time referred to the continent of Africa in general. What is now coastal Libya was known as Tripolitania and Pentapolis, divided between the Africa province in the west, and Crete and Cyrenaica in the east. In 296 AD, the Emperor Diocletian separated the administration of Crete from Cyrenaica and in the latter formed the new provinces of "Upper Libya" and "Lower Libya", using the term Libya as a political state for the first time in history.

Byzantine rule in North Africa spanned around 175 years. It began in the years 533/534 with the reconquest of territory formerly belonging to the Western Roman Empire by the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire under Justinian I and ended during the reign of Justinian II with the conquest of Carthage (698) and the last Byzantine outposts, especially Septem (708/711), in the course of Islamic expansion.

Roman colonies in North Africa are the cities—populated by Roman citizens—created in North Africa by the Roman Empire, mainly in the period between the reigns of Augustus and Trajan.