Samba is a lively dance of Afro-Brazilian origin in 2/4(2 by 4) time danced to samba music.

Candomblé is an African diasporic religion that developed in Brazil during the 19th century. It arose through a process of syncretism between several of the traditional religions of West Africa, especially those of the Yoruba, Bantu, and Gbe, coupled with influences from the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. There is no central authority in control of Candomblé, which is organized around autonomous terreiros (houses).

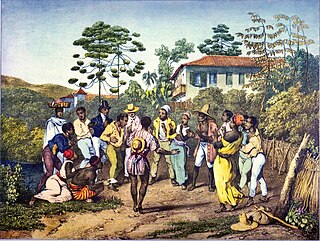

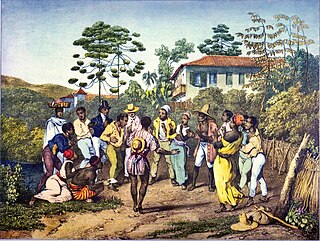

Lundu is a style of Afro-Brazilian music and dance with its origins in the African Bantu and Portuguese people.

Candomblé Ketu is the largest and most influential branch (nation) of Candomblé, a religion practiced primarily in Brazil. The word Candomblé means "ritual dancing or gather in honor of gods" and Ketu is the name of the Ketu region of Benin. Its liturgical language, known as yorubá or Nagô, is a dialect of Yoruba. Candomblé Ketu developed in the early 19th century and gained great importance to Brazilian heritage in the 20th century.

Afro–Latin Americans or Black Latin Americans are Latin Americans of full or mainly sub-Saharan African ancestry.

Afro-Brazilians are Brazilians who have predominantly sub-Saharan African ancestry. Most members of another group of people, multiracial Brazilians or pardos, may also have a range of degree of African ancestry. Depending on the circumstances, the ones whose African features are more evident are always or frequently seen by others as "africans" - consequently identifying themselves as such, while the ones for whom this evidence is lesser may not be seen as such as regularly. It is important to note that the term pardo, such as preto, is rarely used outside the census spectrum. Brazilian society has a range of words, including negro itself, to describe multiracial people.

The term maracatu denotes any of several performance genres found in Pernambuco, Northeastern Brazil. Main types of maracatu include maracatu nação and maracatu rural.

The term afoxé refers to a Carnival group originating from Salvador da Bahia, Brazil in the 1920s, and the music it plays deriving from the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé religion. It came to indicate a musical rhythm, named ijexá derived from the ijexá nation within Candomblé. Cultural performances of the afoxés, typically at Brazilian Carnival, incorporate choreography, song, ritual language and ceremonies deriving from the Candomblé religion. In Brazil, afoxé is generally performed by blocos, afros-groups of mostly black or mulatto musicians who are familiar with African Brazilian music. Afoxés are a cultural and religious entity that preserves a tradition of Afro-Brazilian culture.

Batuque (drumming) was a general term for various Afro-Brazilian practices in the 19th century, including music, dance, combat game and religion.

Slavery in Brazil began long before the first Portuguese settlement. Later, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor during the initial phases of settlement to maintain the subsistence economy, and natives were often captured by expeditions of bandeirantes. The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries. Europeans and Chinese were also enslaved.

São Francisco do Conde is a municipality in the state of Bahia in the North-East region of Brazil. São Francisco do Conde covers 262.856 km2 (101.489 sq mi), and has a population of 40,245 with a population density of 150 inhabitants per square kilometer. It is located 67 kilometres (42 mi) from the state capital of Salvador. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics São Francisco do Conde has the highest concentration of Brazilians of African descent (90%) in Bahia.

Maragogipe is a municipality in the state of Bahia in the North-East region of Brazil. Maragogipe covers 438.18 km2 (169.18 sq mi), and has a population of 44,793 with a population density of 110 inhabitants per square kilometer. Maragogipe is located 130 km (81 mi) from the state capital of Bahia, Salvador. It borders the Paraguaçu River, 20 km (12 mi) upstream from Baía de Todos os Santos. Maragogipe was a major center of sugar cane and tobacco production, and became home to large slave-holding plantations. After the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888 the Afro-Brazilian population lived as tenant laborers until recently as "21st century slaves", unable to fish or grow staple crops.

Racism has been present in Brazil since its colonial period and is pointed as one of the major and most widespread types of discrimination, if not the most, in the country by several anthropologists, sociologists, jurists, historians and others. The myth of a racial democracy, a term originally coined by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre in his 1933 work Casa-Grande & Senzala, is used by many people in the country to deny or downplay the existence and the broad extension of racism in Brazil.

Angolan Argentines are Argentine people of Angolan descent or an Angolan naturalised Argentinian. Most of them arrived as slaves during the Spanish colonial period. Currently, the Afro Argentine make up 0.4% of the population, and some are partially descendant from slaves from Angola.

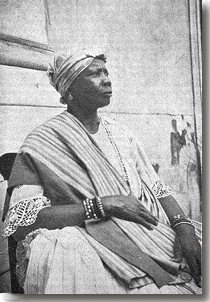

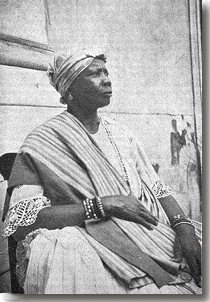

Mãe Menininha do Gantois also known as Mother Menininha do Gantois, was a Brazilian spiritual leader (iyalorixá) and spiritual daughter of orixá Oxum, who officiated for 64 years as the head of one of the most noted Candomblé temples, the Ilê Axé Iyá Omin Iyamassê, or Terreiro do Gantois, of Brazil, located in Alto do Gantois in Salvador, Bahia. She was instrumental in gaining legal recognition of Candomblé and its rituals, bringing an end to centuries of prejudice against Afro-Brazilians, who practiced their faith. When she died on 13 August 1986, the State of Bahia declared a three-day state mourning in her honour, and the City Council of Salvador held a special session to pay tributes to her. The Terreiro do Gantois temple has been declared a protected national monument.

Eugênia Anna Santos was a Brazilian Iyalorixá. She founded the candomblé Ilê Axé Opó Afonjá in Salvador, now considered a National Historic Landmark, and in Rio de Janeiro.

Ilê Axé Iyá Nassô Oká is a historic Candomblé temple in the city of Salvador, Bahia, in northeastern Brazil. It is also known as the Casa Branca do Engenho Velho, or simply the Casa Branca. Located on a hill above Vasco da Gama, a busy avenue in the working-class neighborhood of Engenho Velho, the terreiro belongs to the Ketu branch of Candomblé, which is heavily influenced by the religious beliefs and practices of the Yoruba people. The earliest documents proving the temple's existence are from the late nineteenth century, but it was certainly founded much earlier, probably c. 1830. Since the 1940s, the religious community has been registered as a public entity under the name Sociedade Beneficente e Recreativa São Jorge do Engenho Velho.

Terreiro do Bate Folha, Mansu Banduquenqué , or Sociedade Beneficente Santa Bárbara do Bate Folha, is a candomblé terreiro located in Salvador, Bahia. It was founded in 1916 by Tata Manoel Bernardino da Paixão and is currently chaired by Tata Muguanxi, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima. The terreiro, historically affiliated with Candomblé Bantu, has the largest remaining urban area of the Atlantic Forest, approximately 15.5 hectares. It was listed by IPHAN on October 10, 2003.

Afro-Brazilian culture is the combination of cultural manifestations in Brazil that have suffered some influence from African culture since colonial times until the present day. Most of Africa's culture reached Brazil through the transatlantic slave trade, where it was also influenced by European and indigenous cultures, which means that characteristics of African origin in Brazilian culture are generally mixed with other cultural references.

Candomblé formed in the early part of the nineteenth century. Although African religions had been present in Brazil since the early 16th century, Johnson noted that Candomblé, as "an organized, structured liturgy and community of practice called Candomblé" only arose later.